Over the summer of 2021, Oxy Arts hosted Encoding Futures: Speculative Monuments for L.A., an artist residency where four artists, Nancy Baker Cahill, Audrey Chan, Joel Garcia, and Patrick Martinez, were commissioned to create original, site-specific augmented reality monuments for a future Los Angeles. You can read each of the artists' reflections on their process in this series of articles and learn more about their projects here.

For Los Angeles, what good are land acknowledgments if folks can’t even name any of the living, present-day residents, and Tribal members of the lands you’re acknowledging?

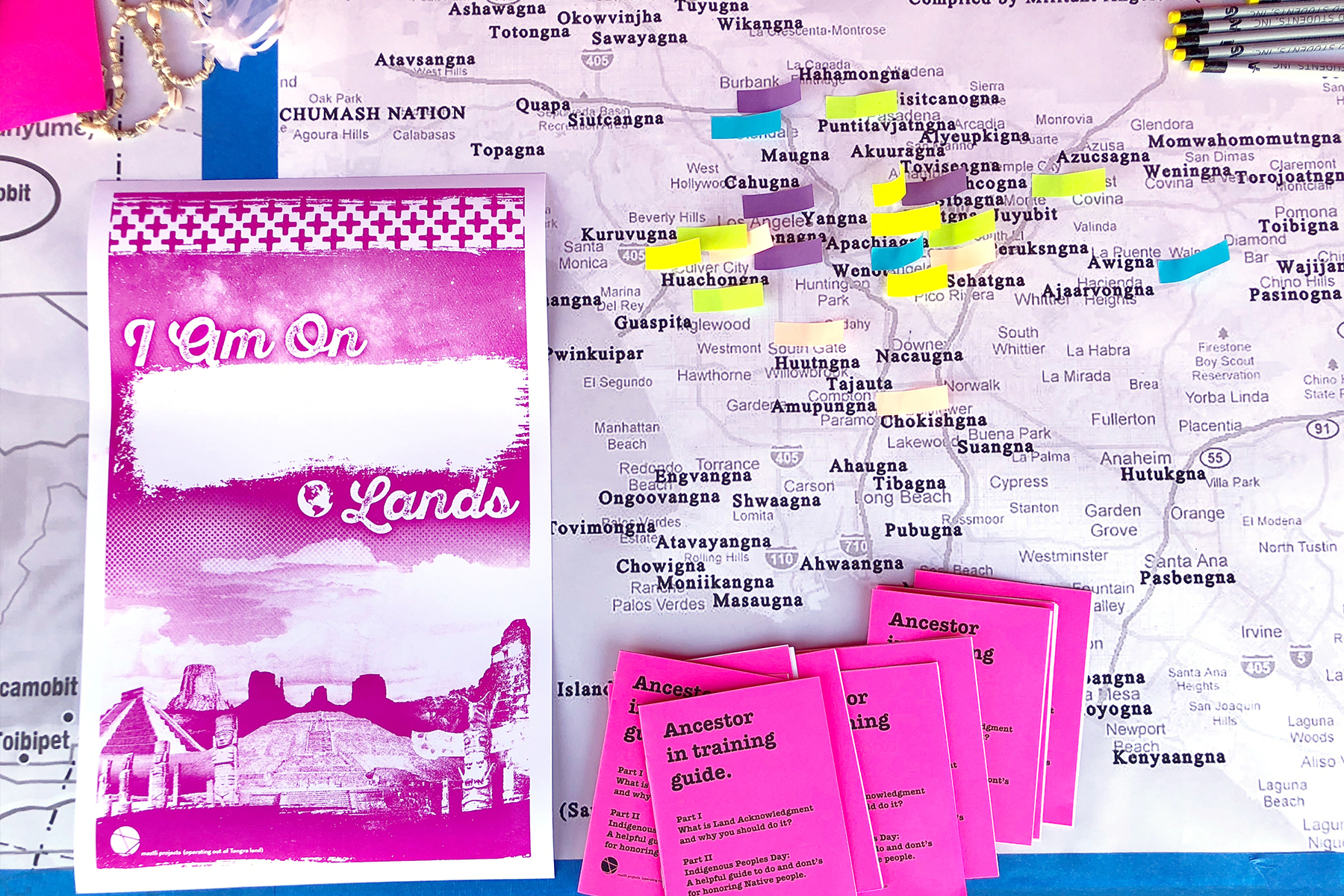

Land acknowledgments are important. In fact, I’ve produced several zines and workshops about them. Yet they are also ever-evolving. Through this project and residency about memory, place, and reimagining the role of monuments, I also want to propose closing the gap between the “acknowledgment” and the actual process of building relations with Tribal communities and of “land return.”

In my work with monuments and how public space is shared, or not, what has stuck with me the most has been the misalignment between our purported values and priorities as a society and how our cities honor people and memorialize events.

I was born and raised in Los Angeles, more specifically in the “projects” in East LA, and it always felt like everywhere we went, or wanted to go to, we were restricted by an unspoken set of protocols; we were either policed in a specific way or we couldn’t go places because of gang violence. But I never let that prevent me from venturing out. I went to backyard punk shows in neighborhoods of rival gangs, I also made it my mission to know Los Angeles, from its underground scenes that welcomed the misfits to the “whitest” of spaces that didn’t want “brown kids” there, such as art school.

Over the last decade, my art practice has focused on what healing, reconciliation, and as of late, reckoning look like for folks like me who grew up in the gang world/street violence of the late 1980s and 1990s. These reflections along with my work with arts programming led me to examine how public space and folks like me interact.

I think about the ways Brown and Black boys are pathologized the moment they step out the door, and how the built environment itself is meant to oppress, criminalize, incarcerate, and banish them. Such systems of surveillance and punishment are rooted in Spain’s colonial plans that indoctrinated and converted Native people in Los Angeles and across California; the system of Spanish Missions across the state were meant to criminalize, incarcerate, enslave, and banish.

From an Indigenous perspective, to heal these wounds we must reconnect with our ancestral lands.

Tongva cultural bearer Craig Torres always shares the need to decenter humans from finding solutions to today’s problems such as the climate crisis. This is critical to the approach of Astrorhizal Networks. Monuments as we have experienced them in the United States almost always celebrate the acts of cis-hetero white men and embellished narratives of their achievements. For example, on the south side of City Hall is a fountain dedicated to Senator Frank Putnam Flint,1 the man who helped steal water from the Owens Valley,2 ancestral homelands of the "Nu-Mu" (Paiute), who have been displaced partly to supply Los Angeles water.3 Soon after the removal of the Christopher Columbus statue in November of 2018 at Grand Park,4 which had been delayed because the county kept insisting there was no money to facilitate this process, they rededicated the Fort Moore Pioneer Memorial, the largest bas-relief military monument in the U.S. commemorating the Mormon Battalion and the New York Volunteer American military forces that first raised the American flag in the recently “acquired” California territory, a renovation cost of $5.5 million dollars.5 Lastly, even the most well-intentioned efforts by folks can create harm such as the monument to Poet Lewis MacAdams, who is credited with advocating for the revitalization of the Los Angeles River through his work with Friends of the LA River (FoLAR).6 Harm materializes in many forms, at times in invisible forms, and in this case, when a settler society anoints someone as an expert over the original stewards of the land, it also establishes a power hierarchy, shifting the power of who gets to tell history, or in these cases, false narratives.

For me, there’s a direct line between the wealth dedicated to upholding these false narratives and the disinvestment in communities like mine in East LA. For instance, the Junipero Serra statue in Downtown Los Angeles was toppled on June 20, 2020 as part of a ceremony.7 We opened up that space to cleanse it, remove trauma, and code in a future where this city’s First Peoples are visibly present, heard, embraced, and supported. But the city relocated the Serra statue to a climate-controlled warehouse. At the height of the uprising for racial justice, as cases surged during the COVID-19 pandemic, and as homelessness was increasing in the city, a statue that stood and endured exposure for almost a century had finally fallen, but now sits shielded from the weather. None of that care is offered to the unsheltered folks that live in the park where this statue stood. In 2014, a fence was installed around the statue, it seems, in order to keep unsheltered folks from sleeping next to it.8 How ironic given that the narrative that was at the center of the 2015 campaign to offer sainthood to Serra was that he was a man that offered shelter to the “savage natives.”

These monuments, from small and obscure to massive and conspicuous, suppress histories and enact violence.

I’ve always been techy, and technology can be very useful for flattening hierarchies; take, for example, file-sharing. I firmly believe in open sourcing everything. Especially history.

Imagine a monument that allows you to text or voice record your own experience too. Imagine being able to record your grandparents’ experience and add it to your city’s archives. I see street memorials all over this city and often wonder which people or person left it at that spot and who it's for. What if we could use technology to honor that person’s story?

Day of the Dead, as celebrated in some parts of Mexico, offers us the concept of dying three times: the first when your body fails, the second, at your burial and funeral, and the third when you’re forgotten.

As much as Astrorhizal Networks is about the futurity of this city, it’s also very much about re-coding the past. Not forgetting. I believe that ceremonies and the practices of healing used by Indigenous communities all over the world are about accessing our body’s code and opening it up for re-coding, coding out our traumas, and coding in beauty. But for this, we must be connected to the land. Be caretakers of the land, stewards of our ancestors. Literally, as our past and future are held there.

So how can monuments nurture, teach, communicate, and learn?

Our handheld devices already carry the technology to tap into so much knowledge. What if these phones and tablets could be used in public spaces so that we could hear the voices of ancestors? What if I could walk onto places where we’ve built over important sites and hear their original names, Puvuungna (Cal State University, Long Beach), Kuruvungna (University High School) and so on?9 What if I could walk onto El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument (Olvera) and listen to the stories of the past, but also the present and the future? What if monuments helped us heal and understand each other better?