I was brought up mostly around my mother’s big family, the majority of which currently consists of women. My mother was a heavyset woman; she swayed as she walked and took very purposeful steps. She had an unconquerable spirit that radiated power, strength, and assertiveness with every step she took. Her eyes spoke to you first; a look kept you on your toes, followed by a smile that brought you warmth. An immigrant to the United States, my mother fought for her family, fronting the costs of many relatives to immigrate also. A lot of the women in my family have shouldered unimaginable burdens, and my mother was instrumental in creating a foundation to stabilize their transition.

A lover of self, my mother cherished having her picture taken and as children, my siblings and I loved indulging in this with her. She reveled in being the subject, often assuming the iconic pose of Rose in Titanic. Even in her final days, my mother’s vibrant presence obscured the reality of her impending death. Decades later, what remains are these images that immortalize her and emanate her grandeur. In each photograph, she looks directly into the camera, her gaze powerful and captivating. She was never a passive subject, but an active force. Her presentation leaves a lasting impression, her presence almost tangible. The weight of each photo is a testament to her influence and the void left in her absence.

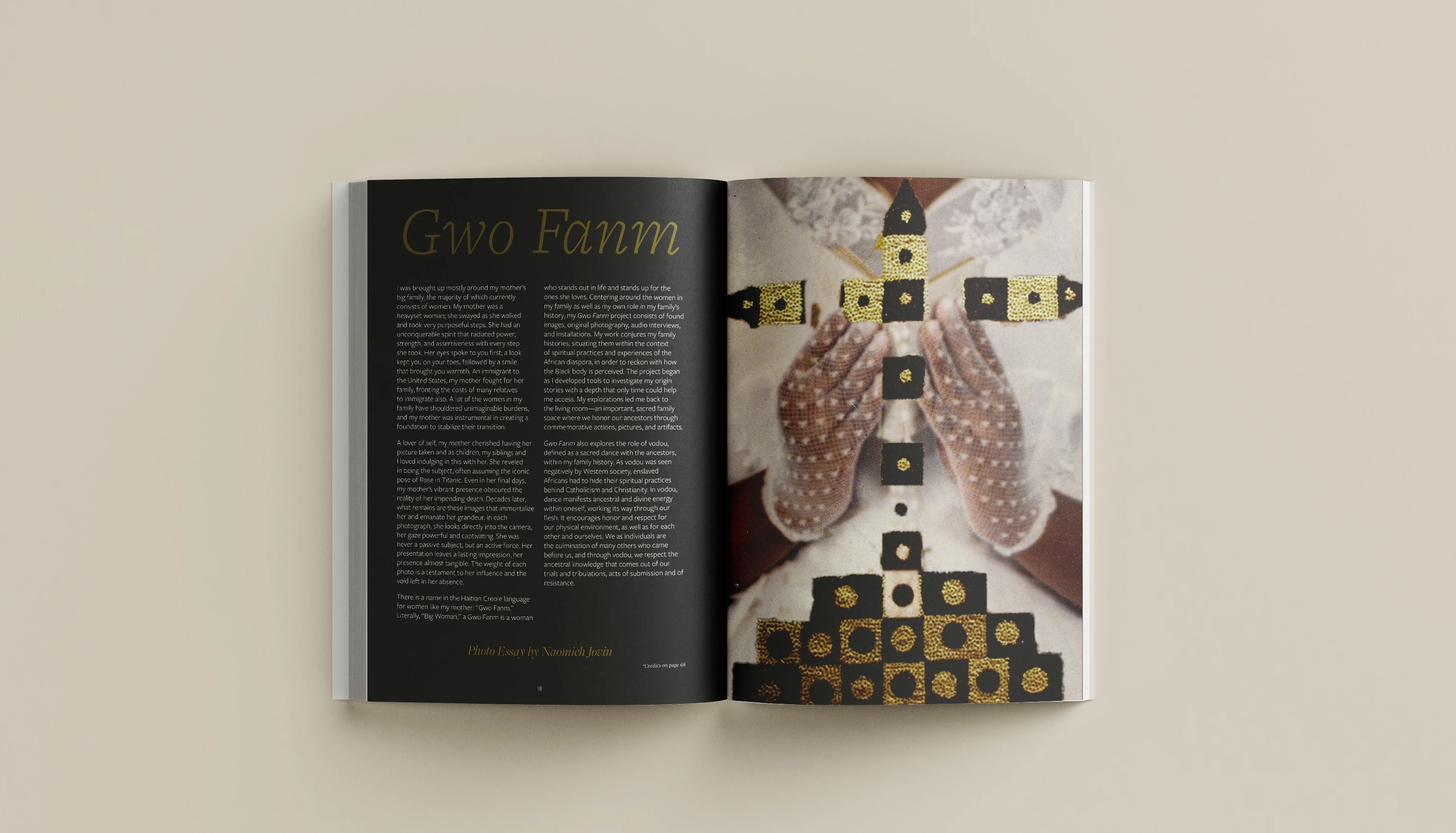

There is a name in the Haitian Creole language for women like my mother: “Gwo Fanm.” Literally, “Big Woman,” a Gwo Fanm is a woman who stands out in life and stands up for the ones she loves. Centering around the women in my family as well as my own role in my family’s history, my Gwo Fanm project consists of found images, original photography, audio interviews, and installations. My work conjures my family histories, situating them within the context of spiritual practices and experiences of the African diaspora, in order to reckon with how the Black body is perceived. The project began as I developed tools to investigate my origin stories with a depth that only time could help me access. My explorations led me back to the living room—an important, sacred family space where we honor our ancestors through commemorative actions, pictures, and artifacts.

Gwo Fanm also explores the role of vodou, defined as a sacred dance with the ancestors, within my family history. As vodou was seen negatively by Western society, enslaved Africans had to hide their spiritual practices behind Catholicism and Christianity. In vodou, dance manifests ancestral and divine energy within oneself, working its way through our flesh. It encourages honor and respect for our physical environment, as well as for each other and ourselves. We as individuals are the culmination of many others who came before us, and through vodou, we respect the ancestral knowledge that comes out of our trials and tribulations, acts of submission and of resistance.

About Bulletin

This story is featured in the inaugural print issue of Bulletin, a public art and history print journal offering perspectives on critically reading and reimagining monuments. We collaborate with artists, scholars, curators, activists, and writers to question the symbols and systems that we have inherited—and to envision new directions and pathways for public memory.

Edited by Patricia Eunji Kim, this issue explores the theme of “Ghosts.” Contributors Charles Athanasopoulos, Jeanne Dreskin, Paul Farber, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Naomieh Jovin, Cannupa Hanska Luger, Shannon Mattern, Nicholas Mirzoeff, TK Smith, and Marisa Williamson consider the specters, haunting sensations, and eerie remnants of the past as they relate public art, space, and memory. Learn more and buy a physical copy of the full Bulletin today!