From Civil War Monuments and the Militarization of America by Thomas J. Brown. Copyright © 2019 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.org

Beyond the Iconoclastic Republic

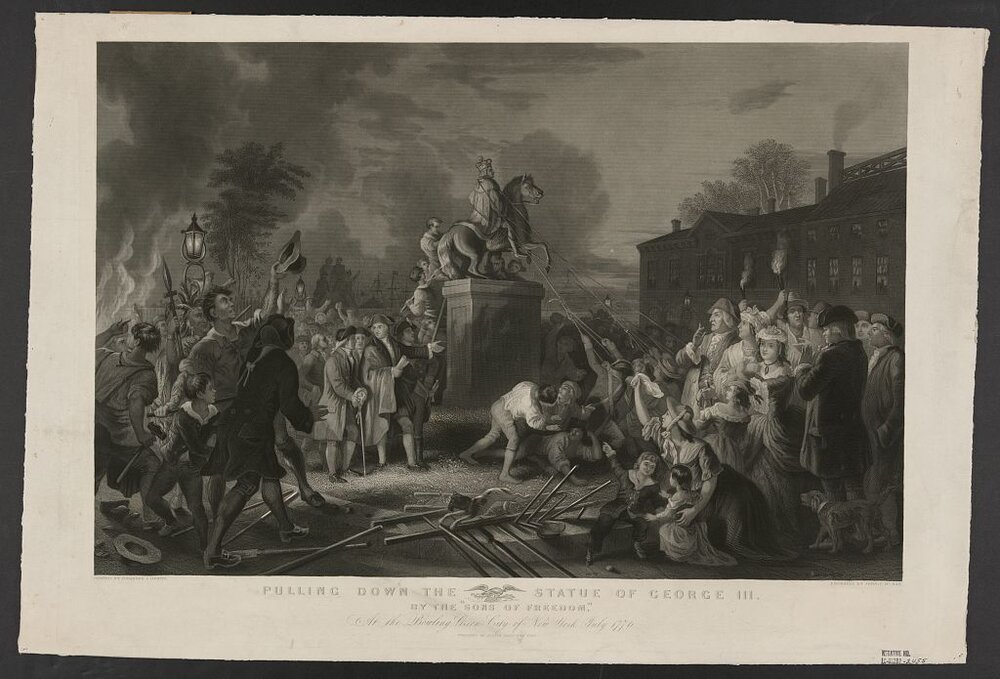

American memory began in iconoclasm. After the public reading of the Declaration of Independence ordered by George Washington upon arrival of the document in New York City on July 9, 1776, a crowd surged to Bowling Green and tore down the equestrian statue of George III dedicated six years earlier. This symbolic regicide was a profoundly antimilitary protest. Since antiquity, the equestrian monument had been an emblem of imperial authority precisely because it depicted the sovereign as a military commander. Even if a monarch like George III was hardly prepared to lead troops in the field, the king’s statue in lower Manhattan complemented the adjacent garrison that enforced his royal authority. American commemoration developed in accordance with the hostility toward standing armies central to the Revolution. Through the first half of the nineteenth century, the most prominent outdoor monuments to Washington in the nation’s capital, New York, and Baltimore showed the general giving up his authority at the end of the war and dramatizing a radical disjuncture of military and political governance. Americans often observed that public monuments were less compatible with democracy than other modes of remembrance, especially print.1

The Civil War monuments installed by communities across the North and South from the 1860s into the 1930s transformed the civic landscape and the place of the military in national life. The United States became a leading contributor to the transatlantic canon of war memorials. This highly decentralized process yielded many different commemorations, but prevailing patterns emerged. The introduction of the common-soldier monument responded to the crisis of Civil War death without immediately relinquishing antebellum reservations about martial institutions. Early tributes to military and civilian leaders also expanded creatively on prewar precedents. As the shock of the carnage faded, however, a second proliferation of monuments assumed a different cast. Often dedicated to veterans, these memorials identified soldiers as exemplars of a robust, disciplined citizenry. Commander statues idealized hierarchical leadership. Celebrations of victory shifted emphasis from regeneration to affirmation. Civil War monuments reshaped remembrance of the Revolution and helped to divert American conceptions of World War I from the anguished meditations of the Allied Powers. Cultural form invigorated ideology in the metamorphosis of the country from an iconoclastic republic to a militarized nation.

This militarization included symbolic and practical dimensions. The establishment of the American war memorial shaped the broader evolution of public monuments in the United States and the development of other patriotic practices. Art historian Dell Upton has recently underscored the pervasive legacy of Civil War commemoration by observing that even monuments to the mid-twentieth-century civil rights movement, a heroic demonstration of democracy grounded in doctrines of nonviolence, routinely turn to martial iconography as emblematic of citizenship.2 Contrary to the hopes of the iconoclastic republic, military monuments became an authoritative representation of the nation. That shift not only correlated with but preceded and facilitated policy developments. Civil War monuments, which became more belligerent during a period of international peace, modeled the forcible imposition of labor and racial order amid late-nineteenth-century struggles over the prerogatives of industrial capitalism and white supremacism. Veneration of soldiers also advanced military measures like the consolidation of a veterans’ welfare state and the restructuring of an expanded army.