This summer, President Trump signed an executive order calling for the construction of a National Garden filled with statues of “American heroes.” The proposed sculpture park—which includes an unwieldy list of former presidents, baseball players, clergy members, generals, and explorers—came as activists toppled and defaced racist monuments throughout the country.

The timing was no coincidence. Faced with a powerful movement against symbols of violence and oppression in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, Trump effectively dug in his heels, signaling his alignment with long-standing white supremacist and Eurocentric views on how monuments should look—and what purpose they should serve. Take the order’s call for “realistic” representations of historical figures as opposed to abstract or modernist renderings. This preference reflects a nostalgic longing for neoclassical ideals of the Italian Renaissance, which combined concerns for perspective, scale, and life-imitating accuracy with the veneration of god-like human figures.

Trump may be on his way out of power, but America’s white nationalist movement will endure—as will its well-documented inclination toward a neoclassical aesthetic that links concepts of beauty to whiteness and wealth. As demonstrators continue to counter this force in the age of #TakeItDown, however, it’s worth asking: What kind of monuments should take their place? How can we move beyond the attachment to permanence and neoclassical representations to craft more liberatory symbols in the landscape of public memory?

For decades, artists have answered those questions by creating monuments that use modes of mimicry, collectivism, and ephemerality. In doing so, they’ve crafted a new memorial vernacular and challenged the very meaning of monuments.

Mimicry and Subversion

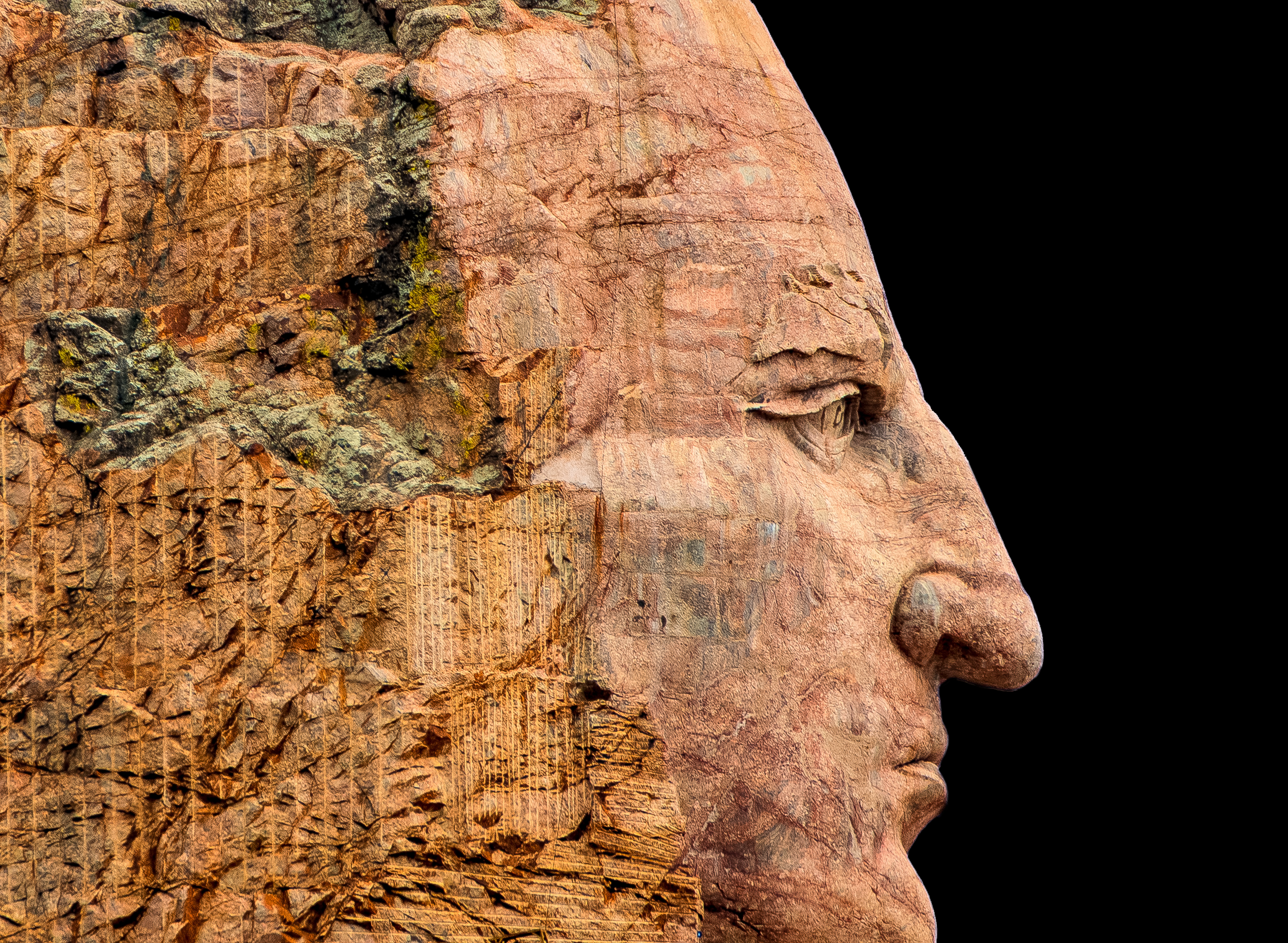

Trump’s choice to announce his executive order at the foot of Mount Rushmore—a colossal monument that actively obscures the violence of the nation’s founding—is significant. To the Lakota Sioux, the original inhabitants of the area, the carvings of the presidents’ faces are a desecration of the sacred Black Hills and an ugly reminder of the triumph of European settlers who appropriated their land and massacred their people.

In 1939, to counter the abomination of Rushmore, Sioux Chief Henry Standing Bear invited sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski to carve a “counter-memorial” to Native American history nearby. The monument depicts the great Sioux Chief Tasunke Witko—known as Crazy Horse—best known for taking up arms against the encroachment of white settlers during the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. The sculpture, which is still under construction decades later, will be the largest in the world. Although many Lakota see the monument as a necessary counterpoint to the glories of Western expansion, some see a cruel irony in it. For one, its construction constitutes a continued desecration of sacred burial grounds. And, as Brooke Jarvis reported in The New Yorker, others see it as a money-making scheme that would’ve horrified Crazy Horse, a man who never wanted to be photographed and even requested to be buried in an unmarked location.

Does the Crazy Horse “counter-memorial” address Rushmore’s offenses by essentially micking its form of hero worship? In his article “Of Mimicry and Man,” Homi Bhaba describes mimicry as potentially subversive.1 The colonized can performatively mirror particular codes of behavior or language associated with the colonizer in order to expose the hollowness of imperial power.

Take Touissaint Louverture, a formerly enslaved man who fought French colonial forces during the Haitian Revolution. Fully grasping the symbolic force of the European equestrian portrait, in 1802 Louverture rendered an iconic image of himself on horseback, dressed like Napoleon and carrying a sabre. While the French eventually exiled Louverture and reinstated slavery in the Americas, the iconic image of an armed Black man on horseback continued to drive the imaginations of the enslaved.2

Over 100 years later, Kehinde Wiley appropriates the same monumental vernacular in his bronze monumental statue Rumors of War, which depicts a Black man on horseback, with dreadlocks, ripped jeans, and Nike high-tops. Unveiled at the Virginia Museum of Fine Art in December 2019, the figure assumes the heroic pose of one of the high-ranking Confederate Army officers whose equestrian statues still line Richmond’s Monument Ave.

If, as Bhaba argues, colonial mimicry requires “slippage” to function subversively, Wiley’s rider, with his frayed denim and unknown identity, expresses a tender vulnerability that refuses to completely replicate the Confederate tributes on which it is based. Perhaps it is this ambivalence that is missing in the Crazy Horse memorial in its attempt to match, and even exceed, the grandeur of Mt. Rushmore. Mimicry thus presents us with a tightrope between the subversion and reinstatement of power.

Collectivizing Responsibility and Power

If conventional monuments celebrate national triumphs through heroic, self-aggrandizing icons, counter- or anti-monumentality promotes anti-heroic installations that encourage multiplicity and public interaction.

“Anti-monument” was the disparaging label applied to Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial when it was announced as the winning submission of a 1982 monument design competition. At the time, Lin’s simple black granite wall was seen as “nihilistic” and “degrading,” with donors in closed door meetings scrambling to tack on realistic statues of American soldiers to incorporate a more triumphant message. In the end though, her minimalist design endured, with its mirror-like surface blending reflections of the living with the names of the dead.

Despite serving as an open-ended signifier that encouraged visitors to bring their own interpretations to the site, its reflective veneer remains limited. The list of casualties does not include the names of the Vietnamese who died, and, as Kirk Savage points out, its location alongside several other war monuments ends up justifying future imperial interventions.

Where Lin’s design fails to hold up a mirror to the crimes of state violence, other monuments have risen to the occasion. The Mirror Casket project is a sculpture and performance piece created in 2014 by a team of seven community artists and organizers as a response to the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson. The mirrored casket was first activated on the shoulders of pallbearers who carried it in a silent funeral procession to the Ferguson Police Department. On the way, spectators were forced to confront glimpses of their own shattered reflections. While the piece evokes empathy for Black men murdered at the hands of police, the reflective glass sends a deeper message of collective complicity in racist violence—and our responsibility to dismantle it.

Beyond reflections of grief and complicity, collectivizing monuments can also celebrate the masses. Do Ho Suh’s sculpture “Public Figures” literally flips the blueprint of the heroic monument upside down. Its large pedestal remains empty, but if you look closely you’ll see a procession of several hundred tiny figures holding it up from below. Suh envisioned an element of trickery as well, whereby the plinth would be moved to different places after dark, as if the masses had painstakingly hauled it inch by inch.

Collectivizing interventions into the memorial landscape can therefore move us away from hero worship towards a recognition of the masses—forcing an internal reckoning with our complicity as much as our power.

Ephemerality and Absence

In the aftermath of World World II, German artists grappled with how to memorialize the Holocaust without aestheticizing it or relaying a false sense of historical closure.3 It wasn’t until the 1980s that a new wave of public art used ephemerality to express absence and loss. Perhaps the most emblematic example is Esther Shalev-Gerz and Jochen Gerz’ 1986 Monument Against Fascism—a 12-meter-tall column in a suburb of Hamburg designed to be gradually lowered into the ground. An inscription at its base invited passersby to inscribe their names into its surface as a pledge against fascism. Yet unlike the Vietnam memorial’s tidy rows of names, the column attracted an array of defacements, from innocent doodles to swastikas. The monument became an ambivalent survey of the public’s relationship to history, a time capsule that was eventually submerged out of sight.

Sometimes the most effective means of exposing the constructed-ness of historical “truth” is through the creation of absence. In 1992, the Maryland Historical Society invited Fred Wilson to create an exhibit that would expose the racial politics of their collections. The result, “Mining the Museum,” opened with the busts of Napoleon, Henry Clay, and Stonewall Jackson next to three empty pedestals inscribed with the names of three important Black Marylanders who were nowhere to be seen in the museum’s archives: Harriet Tubman, Benjamin Banneker, and Frederick Douglass. The simple juxtaposition gave form to an urgent question: What does it take to be memorialized?

While Wilson’s intervention offered a specific challenge to museum practices, other artists and curators have since carried the spirit of his work into the public square. There’s Sharon Hayes, whose 2017 sculptural installation If They Should Ask, uses a composite of empty pedestals to address the absence of monuments to women in Philadelphia. And then there’s London’s Fourth Plinth, which hosts a rotation of contemporary artwork in Trafalgar Square and pushes against the decisiveness of English Imperial power embodied by the permanent, militarized monuments perched on the other three plinths.

If, as WJT Mitchell argues, the goal of all monuments is, traditionally, to “live forever,” proponents of a more liberatory approach to memorialization must respond by approaching future monuments as ephemeral—temporary symbols subject to change and destruction.

As the Trump administration and its allies scramble to preserve the neoclassical grandeur of a mythological past, demonstrators across the world are transforming immortal monuments to white supremacy by applying graffiti, light projections, or by removing them altogether. By doing so, they are asserting themselves into a telling of history that is far from determined.

Our future monuments must recognize this struggle, and above all remain self-conscious in the stories they tell and the truths they honor.