On March 13, 1968, the United States Army performed an aerial test of the extremely toxic nerve agent VX, spraying over 300 gallons of the chemical compound from a jet over western Utah. Military personnel at Dugway Proving Grounds (DPG), a biological, chemical, and incendiary weapons testing facility encompassing 800,000 acres in the Great Salt Lake Desert, carried out and oversaw the maneuver. Dugway had conducted roughly 1,600 such field trials over the previous two decades alone and this particular test was considered routine, though its accidental consequences were anything but.1 Within days, over 6,000 sheep had reportedly asphyxiated on neighboring ranches in Skull Valley, a hilly expanse beyond the Proving Grounds’ northeastern borders. While news outlets speculated on possible human costs of such experimentation, DPG representatives spent weeks denying that the testing had taken place. They later conceded, however, after a Utah Senator released a Pentagon document proving that the facility had indeed released VX on the date in question.

For nearly eighty years, DPG has existed on a secluded swath of Utahan desert, quietly fostering exchanges of power between state, military, and industrial entities. It has become a nexus for legacies of settler colonialism, land appropriation, wartime xenophobia, and environmental racism, demonstrating how desert spaces and communities have been systematically exploited to perpetuate American exceptionalist myths. To grapple with the invisible histories of this violence is to acknowledge a critical need for interventions that address its possible futures.

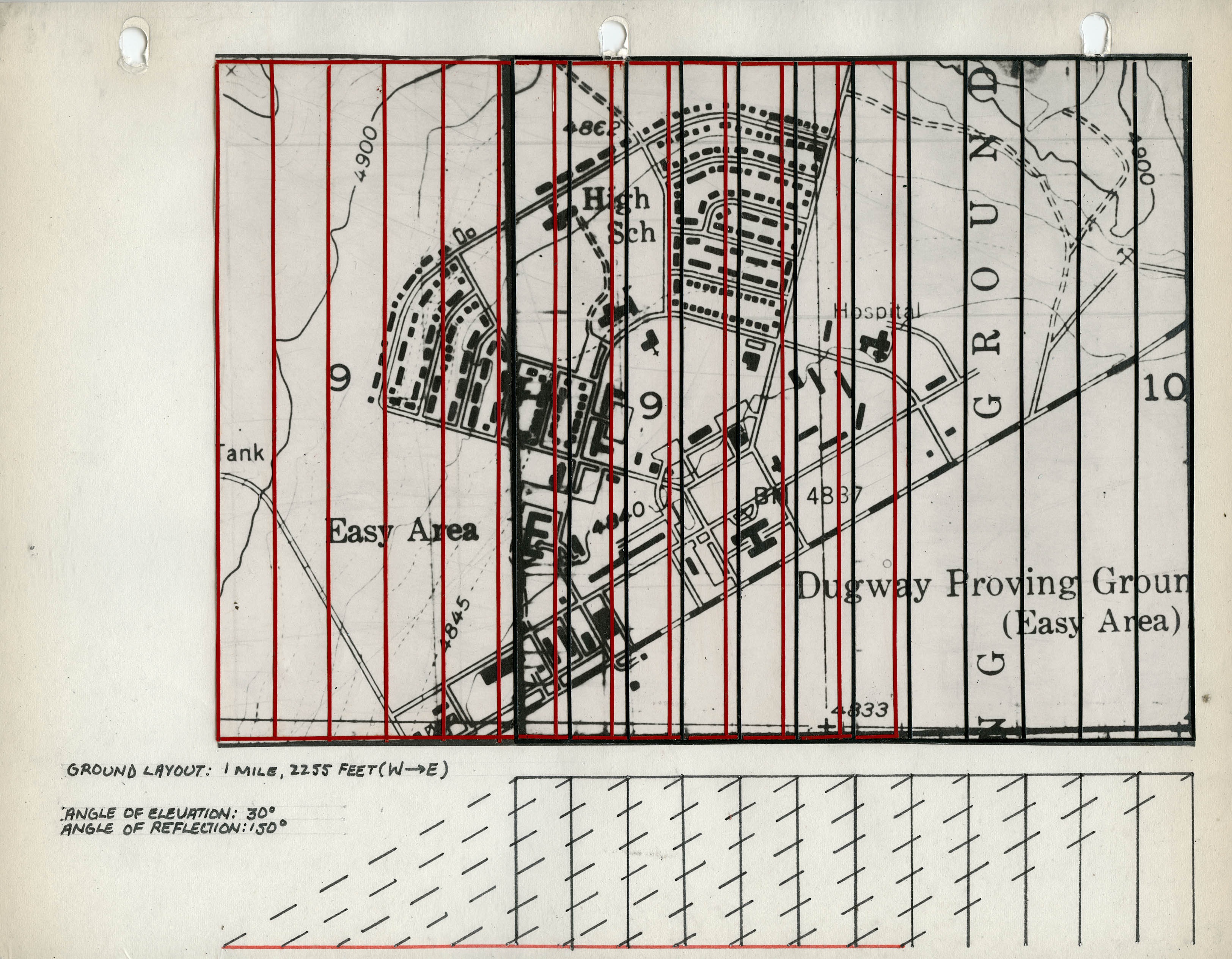

In response to DPG’s 1968 sheep incident, artist Adrian Piper produced Parallel Grid Proposal for Dugway Proving Grounds Headquarters (1968), a thirty-page series of maps, diagrams, and texts outlining designs for a minimalist structure based on the layout of DPG’s testing grid itself.2 The proposed architecture would be installed above the municipality of Dugway, the small neighborhood on DPG grounds where hundreds of onsite staff members and their families resided.3 As the sun rose and set each day, the structure would cast a shifting matrix of linear shadows in the form of the testing grid over Dugway’s built environment, which included homes, schools, businesses, and recreational spaces.4

By appropriating the grid as a template and cartographically transposing it onto the town itself, Parallel Grid Proposal... refigured the municipal hegemonics of mapping. It situated Dugway directly within the hazardous zone of testing, subverting any official claims that DPG performed its biochemical experiments at a “safe” distance from the tiny enclave. By offering a continual visual reminder of the March 13th incident, the structure would also phenomenologically remap Dugway inhabitants’ experiences. A framework of shadows would gradually overlay the test grid onto their environs, making the town’s assumption of an insidiously high level of risk hypervisible. In turn, DPG staff would see and feel their constant proximity to extremely toxic testing with unprecedented awareness.

Conceived as a conceptual work, the structure that Piper imagined remains unrealized in physical space, extant only in its original document form. Ways in which the document ventriloquized administrative idioms of Vietnam War-era technocracy, however, still speak volumes.5 According to the artist’s plans, some of the Dugway structure’s beams would connect a series of telephone cables, which would serve as a conduit for a regular program of public alerts.6 Communication channels including daily announcement broadcasts, phone messages, and electronic billboards would inform residents of DPG activities.7 Typically, DPG experiments performed in the name of “scientific research” carried grave dangers that remained virtually ever present, yet strategically unspoken. Piper’s suggestion to openly impart updates to residents constituted an indictment of these standard operating procedures: it threw into stark relief the veritable “violence-industrial complex” of interwoven corporate, military, and state interests that blanketed DPG tests in opacity at the time.

The resistive gestures underlying Piper’s project, much like her proposed structure itself, transcend the temporal and geosocial contours of their milieu. They emphasize cultures of silence that have historically insulated DPG from public awareness, access, and inquiry. As facility overseers maintain this insulating silence, it continues to threaten present and future lives across DPG’s desert environs.

Closed, Yet Not Contained

Today, DPG remains a “closed post.” The U.S. Department of Defense limits access to residents and any visitors must secure clearance through an internal sponsor. In recent years, several journalists and photographers were offered limited admission following DPG representatives’ claims of wanting to be “more transparent” with the public. Nonetheless, little has diminished the aura of enigmatic, conspiratorial threat looming over the site. Most visual experiences of its facilities are still likely to occur at a significant remove, relegated to distanced observation or formally authorized accounts.

To catch a glimpse of DPG from afar, one could seek a view from about fifteen miles south at Simpson Springs Campground. Looking northward from the camp, vast expanses of dry shrubs and brush blanket the sandy West Desert valley encompassing the two sites. Three checkered red and white water towers signal Dugway’s otherwise unassuming presence, roughly charting the coordinates of its clustered, low-slung structures. Beyond those, more dusty scrubland unfurls for miles in every direction, framed by mountain peaks jutting upward across the distant horizon. From this vantage point DPG seems diminutive, nearly swallowed by the magnitude of its surroundings. It is precisely this sense of colossal isolation that made the land an appealing backdrop for highly noxious and highly classified biochemical weapons testing—the ecological, geological, and physiological repercussions of which will likely far outlast the people responsible for them.

According to scholar Susan Kollin, predominant cultural imaginaries have celebrated American deserts as “prelapsarian, presocial, and premodern” spaces for centuries.8 The impression that these spaces could eschew capitalism’s industrialization and commodification of land, people, and time is, of course, a dangerous fallacy. Mythic understandings of these regions as “blank slates”—untouched by history’s displacements and impervious to uncertainties of the future—continue to enable their appropriation. DPG’s 1968 sheep incident demonstrated just one dire consequence of these spurious logics: if a terrain’s perceived lack of industrial development or settlement deems it “suitable” for biochemical testing, desolation alone makes this testing’s toxic violence no less toxic, no less violent, and ultimately, no more containable.

Abiding Falsehoods of "Firsting"

Wilful perceptions of desert vistas as spaces of emptiness or deficiency have facilitated centuries of American land expropriation by state, military, and industrial interests. While these perspectives clearly justified the establishment of secluded military bases and test sites like DPG, they have deep historical roots in the Euro-American settler colonial project. As writer Rebecca Solnit has noted, “only Europe lacks deserts, and it is mostly through Europeanized eyes that the American desert has been seen, feared, and misunderstood.”9 By calling themselves “Americans,” European settlers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries claimed to be “of” a place whose arid landscapes would have challenged their most entrenched topographic schemas. Nevertheless, steadfast beliefs in the possession and domination of American lands as preordained inheritances compelled their continued advancements.

Settlers’ likely unfamiliarities with deserts rendered their topographies susceptible to overdetermination by imperialist ways of seeing, a phenomenon that historian Jean M. O’Brien has termed “firsting.” By insisting on the inherent primacy and “firstness” of their own paradigms of modernity, Euro-American settlers explicitly repudiated antecedent Indigenous presences, land claims, and lifeways.10 Early American policies codified these beliefs, sanctioning countless acts of land theft and slaughter in pursuit of exhaustively eradicating Indigenous populations and making their land available for white settlers.11 If dry desert lands were already viewed as “empty,” however, those lands could be claimed with less active resistance. Whatever lands could be more easily acquired and controlled as property could more readily feed racialized fantasies of white entitlement to power and resource accumulation. As nineteenth-century dogmas of manifest destiny drove seizure and settlement of Indigenous lands westward, any dissonances that desert vistas may have conjured in their invaders would become eclipsed by rhetorics glorifying the “new frontier.” Desert terrain became a stage across which dramas of this glorification unfolded—a tabula rasa upon which settlers wantonly exerted genocidal will and inscribed narratives of imperial conquest.

DPG's Colonial Heritages

In Euro-American colonizers’ eyes, deserts categorically served their objectives: they stood as perpetually uninhabited landscapes, continually open to extrinsic speculation. Beliefs of this ilk embedded themselves in white patriarchal American discourses, producing popular notions of deserts as topographies to be “discovered” and instrumentalized on the path to modernist progress. In the words of art historian Lucy Lippard, they were “the geography of revelation—simultaneously empty and full.”12 From the early twentieth century onward, these mythologies propagated through wartime nationalisms, animating technologically driven forms of deserts’ material and geopolitical exploitation in an increasingly globalized political order. Military bases and training centers, uranium mining sites, as well as nuclear and biochemical weapons research, testing, and waste storage areas began extracting from desert lands across the American West. As Cold War tensions grew, logics of American exceptionalism that originally drove settler colonialist agendas extended themselves to arms race fervor: the proliferation of militarized nuclear technologies became necessary to reinforce narratives of American abundance and political ascendancy.13

Dugway Proving Grounds’ founding in 1942 is paradigmatic of these cultures of violence. In the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service (CWS) sought to inaugurate new chemical weapons testing and storage facilities.14 The arid, elevated altitudes of western Utah attracted the CWS, and over several months, DPG was built on a desolate tract of desert—a terrain “with elbow room”—about eighty-five miles southwest of Salt Lake City.15 Colonial-era mythologies provided potent historical blueprints for this appropriation: just as Euro-American settlers saw opportunities for amassing and leveraging resources by co-opting desert vistas as property, so too did the CWS in 1942.

Highly dangerous, experimental, speculative, and purportedly “precautionary” operations conducted at and around DPG have perpetuated colonial legacies by repeatedly wagering and threatening non-white populations’ livelihoods, protection, and preservation—all in favor of protecting and preserving state and military claims to power. This is particularly true of Indigenous populations, many of whom continue to reside on reservation lands around DPG, as well as Japanese and Japanese American populations, who were subject to extensive federal campaigns of xenophobic violence and displacement during the second World War.

The civic transactions by which DPG property was acquired demonstrate how vestiges of these imperialist precedents remained deeply embedded in federal agencies’ administration of otherwise “publicly owned” lands. On February 6, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the transfer of most of the land initially acquired for DPG from the public domain. This agreement thereby allocated federally owned lands, which had been taken from Indigenous populations during the prior century, directly to the U.S. Department of War. In 1863, virtually all of the land on which DPG now stands was forcibly ceded to the United States by members of the Shoshone-Goship Tribal Nation. The treaty documenting this undertaking states plainly that white men’s use of those lands would be “forever free and unobstructed” and that the “comfort and convenience” of those men would be protected by the presence of military posts and servicemembers on said lands. As scholar Jodi Byrd has pointed out, it was precisely the continued colonization of Indigenous nations, peoples, and lands that provided the U.S. with the economic and material resources it required to “cast its imperial gaze globally” and participate in technologized geopolitical struggles of the twentieth century.16 DPG has reinforced these colonial attitudes for almost eight decades.

Exceedingly asymmetrical distributions of power have historically dictated military-industrial exploitations of nearby Indigenous communities, which include the Skull Valley Band of Goshute and the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute (both bands of the Goshute Nation). For at least half a century, federal government agencies have developed, tested, and deposited toxic weapons and their wastes in and around lands owned by these communities. In 2006, for instance, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission issued a license for a nuclear waste dump that would store 40,000 tons of reactor byproducts on Skull Valley Goshute lands. Though that storage facility was never erected, Goshute communities have still been surrounded by factory emissions and nuclear and chemical weapons stockpiling and experimentation at other sites, including Deseret Chemical Depot, Envirocare’s low-level radioactive waste disposal, and the U.S. Magnesium Corporation plant. These poisonous encroachments upon Indigenous lives and environments perpetuate environmental racism and colonialism by industrial means, enacting a continued dissolution of Indigenous lifeworlds and an unfettered siphoning and expenditure of Indigenous resources in support of a settler state and its military.

Orchestrate, Simulate, Perpetuate

At its outset, DPG aimed to bolster U.S. abilities to combat (and defend itself from) its perceived World War II adversaries, which included the Empire of Japan. Consequently, the Proving Grounds and their desert environs became loci for federal efforts to orchestrate, simulate, and perpetuate violent offenses against Japanese and Japanese American populations.

In 1943, aiming to gather more serviceable data on the efficacy of new incendiary weapon systems, a series of “detailed reproductions of typical German and Japanese housing forms” were constructed on DPG grounds as bomb test objects. The Japanese-style buildings’ wooden frameworks and adobe brick walls were, according to their planners, designed to correspond with structural characteristics of residences typical of industrial districts in Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka, and other urban centers.17 Workers (including prisoners recruited from Utah jails) outfitted these dwellings with approximations of Japanese domestic furniture.18 They assiduously determined the pieces’ most appropriate configurations and placed them accordingly, hoping to measure their effects on structures’ flammability.19 With this simulative precision, DPG aimed to gauge as accurately as possible how two-story Japanese homes would incinerate upon impact.

In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, the U.S. military would rationalize deploying weapons of mass destruction against civilians through a heuristic of zero-sum thought. Japanese and American lives were presumed to be mutually exclusive and mass death in Japan was deemed necessary to preserve American sovereignty.20 As cultural critic Rey Chow has argued, a deeply ingrained throughline runs between American exceptionalist principles and efforts at legitimizing the bombing of Japan—that of the United States’ “absolute conviction of its own moral superiority.”21 This conviction offered implicit endorsement of the military’s rehearsals of carpet bombing offensives at DPG. The Japanese village stood as a surrogate theater of war, enabling military simulations of Japanese deaths at a “safe” visual, physical, and psychological distance, allowing misconceptions of these deaths as moral imperatives to proliferate and abstract themselves. By facilitating this process, DPG’s landscape reprised one of American deserts’ most consequential historic roles: it became a projection screen for an ideological apparatus that upheld white supremacy as an imperative for guarding the “sanctity” of American nationhood.

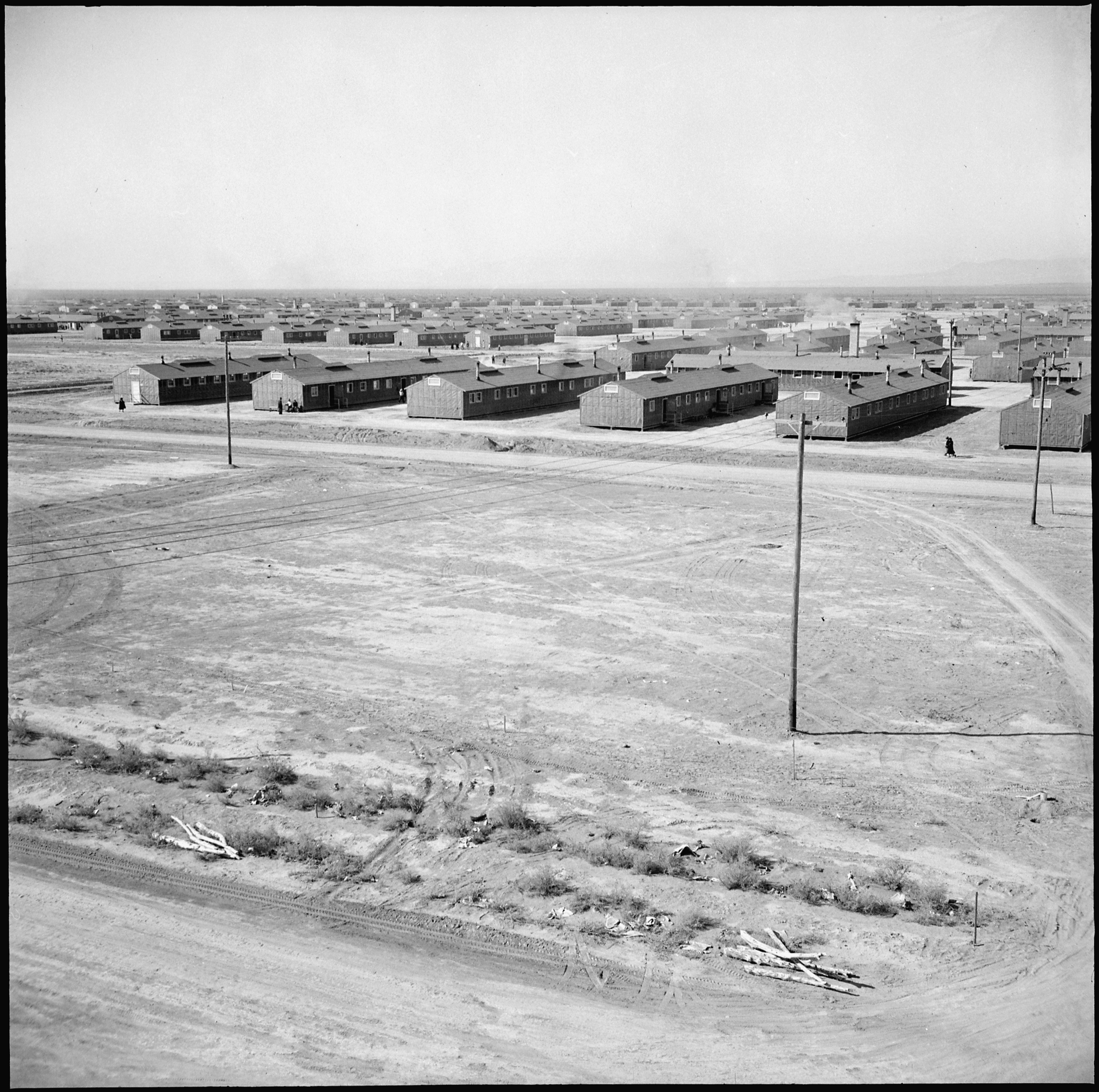

Not seventy miles south of DPG, this ideological apparatus also suffused the historical origins and daily operations of Topaz (also known as “Jewel of the Desert”), the internment camp where roughly 11,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated between 1942 and 1945.22 Just a few months after ground was broken for DPG, construction for Topaz began on a flat, dust storm-prone valley in Utah’s Sevier Desert. The U.S. Army prioritized desolate locations for Topaz and other large camps as a matter of maintaining national security, insisting that all sites be placed on expansive terrain that might discourage or stymie prisoners’ efforts to escape.23 The Sevier’s remoteness and inhospitable climate was therefore seen as advantageous, permitting maximal circumscription, surveillance, and control of Topaz prisoners.

Federal power holders continually relied on racist contrivances of alterity in justifying these waves of displacement and imprisonment. Army general John L. DeWitt, who helped catalyze and direct internment efforts, defended these efforts by characterizing Japanese Americans as an “unassimilated, tightly-knit racial group bound to an enemy nation by strong ties of race, culture, custom, and religion.”24 Heavy trafficking in essentializing stereotypes fueled these discourses’ ideological currency. As Rey Chow argues, stereotypes become most dangerous when they produce otherwise nonexistent realities that political regimes can leverage to support and enact violence for purposes of war, national defense, and protectionism.25 Though most internment camp prisoners were American citizens, federal and military agencies dismissed that reality. Instead, they allowed ethnocentric stereotypes to take precedence, devaluing their own beliefs in the national allegiances that citizenship conventionally demands.

Plans for Topaz were forged through the same racist and xenophobic 1940s rationale that gave rise to DPG’s Japanese village. In both cases, desert conditions proved to be exceptionally hospitable to these illogical paradigms. There, these ways of thinking could unfurl and expand, firmly implanting and replicating themselves in arid seclusion.

An American Mahnmal

In her essay “Building a Marker of Nuclear Warning,” art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson discusses a monument of stone monoliths and text-based signage proposed for the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP), a nuclear waste storage facility in southeastern New Mexico. The monument would have to retain visibility and legibility for at least 200,000 years, the length of time that radioactive matter stored underground at the site might remain lethal.26 Bryan-Wilson debates the potential efficacy of such a monument, charged with carrying an urgent warning across hundreds of millennia whose linguistic evolutions couldn’t be foreseen.27 Attempting to confront this protracted nuclear threat, Bryan-Wilson notes, conjures a “deferred imminence” that challenges conventional imagnings of futurity.28 It underscores the impossibility of conceiving a “known” constant across such an extensive timescale.

If we must imagine a monument to warn future humans of the deadly, insidious creep of nuclear toxicity, we should also imagine monuments that warn against equally enduring, equally insidious beliefs in false virtues of white settler state violence. How can monuments attending to this insidiousness issue dual calls for remembrance and vigilance? How can they telegraph understandings of historical atrocities that mustn’t be repeated, while at the same time imagining disastrous futures that must be avoided?

Like the English word “monster,” “monument” stems in part from the Latin verb monere, to remind or to warn. In German, several terms pertain to monuments’ capacities for transtemporal messaging. As philosopher Susan Neiman has explained, Denkmal might signify the commemoration of a salient event. Mahnmal, however, denotes dovetailing functions of memorializing violence or tragedy and auguring future dangers. German Mahnmale of the later twentieth century, including Berlin’s iconic Holocaust Memorial, are deeply informed by post-World War II processes of Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung, which refers to ongoing practices of recognition and redress through which the country has endeavored to reconcile its culpabilities and complicities in the Holocaust.29 In the U.S., on the other hand, “we don’t want to know about our own national crimes,” Neiman observes. Here, in service of chimeric allegiances to “liberty and justice for all,” authoritative cultures of remembrance too often reflect the state’s attempted sublimation and erasure of its own atrocities.

Adrian Piper’s Parallel Grid Proposal… stages an intervention into these time-honored, quintessentially American conventions of repressing the nation’s incriminating—and patently criminal—histories. If we understand her proposed structure as both a recognition of chemical weapons testing gone awry and an active network for local information distribution, then its inherent refusal to adhere to a single timescale or event horizon becomes clear. While tracking the sun’s shifting position in real time, the Dugway construction would also activate its surroundings through a nexus of temporal registers, gesturing at once to past incidents and to the looming potential for future ones. In this sense, we might consider the structure a would-be Mahnmal. Its gridded shadows and consistent announcements would compel local residents to more vigilantly consider their accountability in—and vulnerabilities to—nearby testing events, whether those be remembered or yet to come. Part sculpture, part sundial, part memorial, part community alert system, it demonstrates how monuments’ capabilities to commemorate and warn can become mutually generative forces.

While inheritances of settler colonialism continue to metastasize through virtually every American institution, in few places are they as emphatically seen and unseen, felt and unfelt, as they are in the fabled “American desert.” Histories of DPG and Topaz demonstrate how imbricated state, military, and corporate bodies have mobilized deserts as tools of dispossession, exploiting imperialist myths that have labeled their topographies as untouched and everlasting.

Ensconced in these myths, federal facilities like DPG become black boxes where violence is imagined and implemented, endangering communities of color under guises of “protection,” “research,” and “precaution.” As long as these enterprises persist, so will our need for monuments that address past and future timescales, that can both excavate buried histories and expose perils hidden in hegemonic silence. As DPG approaches its eightieth year, Piper’s work reminds us: any site where this silence can live and regenerate is a site that will indeed remain dangerous.

The author would like to thank the Adrian Piper Research Archive (APRA) Foundation, Berlin, for their support and assistance in the preparation of this text.