Manuel Acevedo, Cam-Up, Military Park, A Call to Peace, 2019. (Monument Lab)

There is a great peace, after the war great love, after the hatred

– Amiri Baraka

Located in the heart of Newark’s Military Park, one of the nation’s oldest public spaces, a large bronze sculpture sits elevated on a raised pedestal layered with granite on its outer edges. The sculpture, Wars of America (1926), is nearly a century old and was included on the National Register of Historic Places. It forges the middle ground of a park that has been and continues to be a throughway, a gathering place, and a space to consider the multiple narratives that comprise Newark of yesteryear and today.

Wars of America stands out from most other war monuments in Newark and elsewhere, as it elevates a collective of people rather than a single heroic icon. Conjuring references of American conflicts from the Revolution through the Civil War and World War I, this grouping does not merely lionize the leaders of battle or abstract them in dignified poses. All forty-two of the human figures are depicted in the midst of struggles, on and off the battlefield, whether leaning toward conquest or reserved in protection or defiance. In front of the monument, a reflecting pool once extended outward in the shape of a sword, before it was converted more recently into a flower bed.

The purpose of the statue, it seems, was a statement of nationalism enmeshed within perpetual cycles of conflict. When sculptor Gutzon Borglum, later famed for creating Mount Rushmore, looked at his finished statue in the park on Memorial Day 1926, he proclaimed “the design represents a great spearhead. Upon the green field of this spearhead we have placed a Tudor sword, the hilt of which represents the American nation at a crisis, answering the call to arms.”

Though we initially encountered the statue at different times (Salamishah, a native Newarker and Paul, a visiting curator from Philadelphia), our shared relationship to the statue shifted upon learning two facts: first, that Borglum was closely affiliated with the Klu Klux Klan, and second, that he imported part of its granite base from Stone Mountain in Georgia, where he was in the process of designing a Confederate monument.

As a result, we felt that we had a unique opportunity to challenge his “calls to arms” with its opposite and hopeful antidote: A Call to Peace. Our title reflects Military Park as a contested site of pride and patriotism, gatherings and displacement, and memory and historical amnesia.

In addition to the Wars of America, Borglum is the artist behind three other works in the city, including Seated Lincoln (1911), Indian and the Puritan (1916), and First Landing Party of the Founders of Newark (1916). This series of earlier sculptures led into his relationship with city leaders and his commission for Military Park, a statue whose dominance and placement make it hard to ignore and yet difficult to engage. to the South; anti-apartheid activists in the 1980s; and the city’s annual Afro Beat festival today.

On the other side of the park rests a modest but moving historical marker honoring veteran Archie Callahan Jr., the first African American Newark resident killed during the attacks on Pearl Harbor Dec. 7, 1941. It was first dedicated in 1942, but miles away at Douglas Harrison Park, and later moved to Military Park in 2005. These two monuments are touchstones for a park that has and continues to be space at which everyday citizens, soldiers, and veterans meet. It was the gathering space for Union soldiers before they embarked to fight in the Civil War; for Civil Rights workers as they boarded buses going

Chakaia Booker, Serendipity, Military Park, A Call to Peace, 2019. (Monument Lab)

Chakaia Booker, Serendipity, Military Park, A Call to Peace, 2019. (Monument Lab)

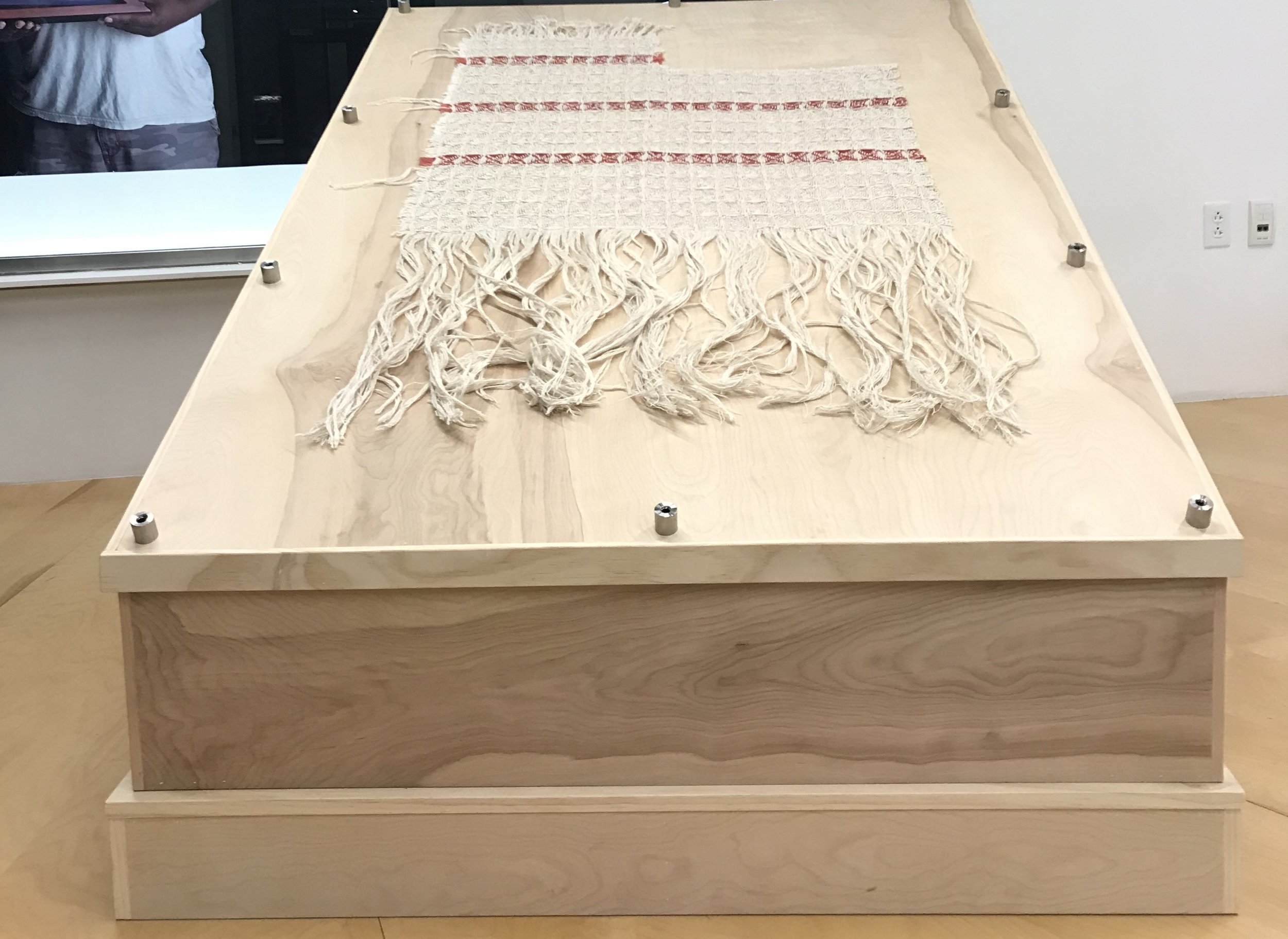

Sonya Clark, Monumental Fragment, Express Newark, A Call to Peace, 2019. (Stephen Smeltzer/Monument Lab)

Jamel Shabazz, Portrait of "Larry 'Free' Dyer," Veterans Peace Project, Military Park, 2019. (Monument Lab)

As the home to some of Newark’s most storied, inherited monuments and bordered by cultural anchors in the city including NJPAC, Express Newark, Newark Arts, and WBGO, Military Park is a power- ful place to engage artists, stu- dents, and city residents around questions about the city’s cultural memory and creative approaches to shaping its next chapters. Today, we see Military Park as a place to conjure new forms of monumental representation and reflection. A Call to Peace is an homage to sacrifice and struggle; dreams of democracy and deferred uplift; and the challenge of living together with the weight of our histories.

Now, as the park’s organizers are in the process of refurbishing the sculpture and officially updating the story told through around it in the park, including telling more truths about its sculptor and what it represents, we ask the central question in our exhibition for the here and now: what is a timely monument for Newark?

A Call to Peace invited four artists – Manuel Acevedo, Chakaia Booker, Sonya Clark, and Jamel Shabazz – all artists known for their innovative ap- proaches to art and social justice to create temporary prototype monuments that take up this question. The artists’ projects offer artworks and activations which respectively focus on underrepresented veterans, engaging the legacies of the Confederate statues, and addressing the relationship between public spaces and historical memory. The artists were invited based on their interdisciplinary and intersectional approaches to monumental work, their relationships with Newark, and their innovative and healing approaches to militarism and/or peace practices.

In a city with a strong artist-activist history, including Black Arts Movement poet Amiri Baraka’s Spirit House, visual artists Gladys Grauer and Jerry Gant, and now its current Mayor Ras Baraka, who himself has a background in spoken word, among others, the moment to reanimate the conversation about art, public space, and justice is now. Building on the momentum of the city’s successful public art projects like “Gateways to Newark,” the art wall at Fairmount Switching Station, and the forthcoming Four Corners, we see A Call to Peace as an invitation to members of the public to help redefine these complex histories and contested public spaces.

Research Lab, Military Park, A Call to Peace, 2019. (Monument Lab)

Alongside the artist installations, New Arts and Monument Lab will open a participatory research lab, staffed by local artists and educators, where passersby will be invited to contribute their own speculative monument proposals. The collected responses will be added to an open database, posted on a community board in Express Newark, and shared as a report to the city in 2020. (The approach is based on similar methods Monument Lab’s team has used in Philadelphia in 2015 and 2017, respectively.)

Every Thursday, the lab will also host weekly "Monumental Conversations" with critical members of Newark’s community who are actively working on issues of monuments, cultural memory, and historic preservation. Our exhibition is not meant as a start to a dialogue, but a gathering of various ongoing threads of critical and creative voices already and continually doing the work.

Our hope is that visitors in Military Park and Express Newark speak with our Lab team; attend events; and submit monument proposals to help collectively unpack, reframe, and reset a viewpoint on what monuments we have and what monuments could define our landscape for the next generation.

In 2019, 400 years after the first enslaved Africans arrived in Jamestown, our nation continues to experience a moment of intensity and uncertainty around public monuments — especially those that symbolize the enduring legacy of racial injustice and social inequality — we are reminded that we must find new, critical ways to reflect on the monuments we have inherited and imagine future monuments we have yet to build. A Call to Peace is envisioned as an opportunity for meaningful dialogue, multidisciplinary approaches to public art and public history, and collective call for social justice.