Mercedes Dorame (Gabrielino-Tongva) is an artist living and working in Los Angeles. Drawing on languages, traditions, and ceremonial practices of her Tongva ancestry, she implements photography and sculpture to newly imagine past, present, and future Indigenous visibilities. The artist engages collaborative, speculative storytelling to intervene into forced erasures of Tongva cultural heritage, reclaiming material and narrative relationships to Tovaangar landscapes (which include present-day Los Angeles). Her images, installations, and temporary monuments explore the politics and poetics of moving through Indigenous spaces, timescales, and forms of knowledge. Her work is currently or has recently been on view at venues across the Los Angeles area, including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Getty Museum; Los Angeles State Historic Park; the Fowler Museum at UCLA; the Art Museum at The Huntington; the Autry Museum of the American West; and the Fullerton Museum Center. She received a Creative Capital Award in 2020 and is currently a member of Monument Lab’s Los Angeles-based Re:Generation team.

Mercedes Dorame with her work Pulling the Sun Back – Xa’aa Peshii Nehiino Taamet, 2021. Installation view at Los Angeles State Historic Park. Photo by Robert Dorame. Image provided by the author.

Jeanne Dreskin: Your MFA at the San Francisco Art Institute and your early work were both rooted in photographic practice. You’ve previously reflected on themes of loss and evidence present in the history of the camera: photographs have been considered indexes of lives, places, and objects lost to time, providing evidence of their previous existences. But you’ve used photography to counter these understandings, demonstrating how Tongva lands, languages, and lifeways were not “lost to time,” but rather forcibly taken. Can you talk a bit about how your relationship to photography has evolved and how it’s been useful in terms of (re)connecting with ancestral histories and forms of Indigenous knowledge?

Mercedes Dorame: I actually started working with the camera on a school newspaper. The idea of objectivity—that the photographer is an unmarked viewer who has no impact on the scene—felt like the ethos around image-making in this realm. When my uncle gave me a Rolleiflex, a medium format film camera, I developed a very slow, measured, ability to work in solitude and I realized that journalistic rules around the use of the camera didn’t fit me. That’s how I found my way into grad school.

During my MFA program, there was a moment where I took some images in the context of work I do as a Tongva cultural consultant on archaeological sites. The pictures were about the environment and the objects that existed in a ceremonial reburial space. It was an experience that was so heavy and emotionally charged that it was hard for me to talk about and not get emotional. But when I showed them in critiques, people were seemingly unaffected by the images. This made me feel like the camera and the photograph had failed me, because something wasn’t coming through in the way that I intended.

Because of this tension, I stopped taking images for a time and started working sculpturally. I worked with found objects, things I had collected that had family history, things from sites that weren’t of scientific value. I was trying to build ephemeral relationships between these objects in a way that built meaning between the viewer and the work. When I came back to the photograph I had a much better understanding of my relationship to the camera. I was talking about ideas of entitlement, and access, and land, and permanence. I had ideas of forcing viewer perspective, engaging people to build an openness or receptivity in a space by giving part, but not all, of a story. When those things clicked in, I felt like I knew when, why, and how to use the camera so that it didn’t feel like it was failing me.

Mercedes Dorame, photograph from the series Living Proof, 2008. Image provided by the author.

When I talk about how Tongva culture wasn’t lost, it was taken, that’s also a shift in perspective. It’s about permanence. Within the ways that Tongva people are viewed and validated by external forces such as the federal government, there’s this idea of ancestry being a continuous line. But historically, you were very discriminated against if you claimed any Indigenous ancestry. When I think of my own interactions with my grandparents…early on, I was frustrated that they were so quiet about so much of my family’s history. But it took a different sociopolitical perspective for me to realize that it wasn’t their fault. So many Tongva cultural practices and a lot of the cultural knowledge...didn’t disappear or evaporate, but it did have to become covert. Now, when I use the photograph in making permanent records of Indigenous presence in landscapes that I have temporary access to, it is not only about reclaiming space and creating an image—one of LA particularly—but also about imaging space in a way that asserts an inescapable presence.

JD: Can you talk a bit about your consulting work, to give some context around the work you mentioned?

MD: Right. As a Tongva person living in Los Angeles, I sometimes work as a cultural consultant on sites where cultural belongings—whether they be things or our ancestors—are being taken out of the ground so that development can happen. There has to be Indigenous representation at these sites and there’s a list of people who are deemed “most likely descendants of the tribe,” so somebody in the community has to be there. My father is one of a few people on the list and has been doing this work for a very long time and he brought me into it.

The site that I referred to earlier was a cemetery. Over 1,000 people, dating back 7,000 years up to post-Mission contact, were taken out of the ground. At this particular site, there was a lot of pushback to stop the removal of these people from their resting place and to have them return to the earth since we were unable to stop it. Finally, six years later, a local councilperson who had a relationship with my father stepped in and helped move the process along. It was a very long, fraught process...we were trying to care for these people and do ceremony, and get them reinterred with their belongings. We would not even want this to be happening in the first place, but in these situations cultural consultants only have the power to “give a recommendation.” You carry the responsibility and the burden of trying to do the right thing to honor your ancestors and the community, but you can’t always get people to listen to you or honor your requests. These experiences made me think about land use, access, development, objectification, and relegating Indigenous people to the past tense. It really pushed me into wanting to talk about a lot of the things that I talk about in my work.

JD: As you discuss these very personal experiences that have influenced your practice, it underscores how your object-making always operates alongside your efforts to reclaim, recode, and recontextualize Indigenous objects, materials, and land. You demonstrate great care for the forms of cultural heritage that these things can carry. Can you speak more about how you see the lives of these objects, materials, and geographies as connected to the lives of Tongva communities not just of the past, but also of the present and future?

MD: When I first started working with objects not in a photographic way, I brought in things that had been passed down, or things like a stone, or a shell, that I had collected from sites of cultural or personal importance. I got interested in working with what I call “star stones”—which are technically called cogged stones—when I worked on a site where many were found. They’re incredibly beautiful and intentionally made and specific to our tribal area and our immediate neighbors. But, we don’t know what they were used for, so there’s this disconnect of their story. Again, this story wasn’t lost, it was taken. Since they’re such incredible objects, this disconnect points to the severity of that taking.

For me, these stones are about star mapping. I’m not saying this is the official Tongva verdict on use or meaning, but it speaks to that ability to create meaning. Working with these objects, sculpting some myself, and allowing them all to be seen in the world...it’s about re-empowering them and myself to tell a story in a way that’s about imagination. I intentionally use the words “cultural belonging” over “artifacts” to describe them. When you say artifacts, you think of things of the past, but cultural belongings have connections to the living, breathing community that still exists in a place.

JD: That brings us to a question I had about collaboration, which could be another way of characterizing the vast relationality of your work with objects like the star stones. Collaboration takes on a multitude of forms in your work--you’ve worked with communities, family members, other artists/designers. In the case of your 2019 interactive installation Tovaangar at the Autry Museum of the American West, you worked with museum visitors. Collaboration with nonhumans, including animals, lands, and environments, is also key to your practice. How would you say collaboration functions in your work, and why are the specificities of places and materials that you choose to work with so important for this?

MD: I actually like this question because I didn’t always see that vein so heavily in my work. I think of myself as being kind of introspective, but I’ve always understood my photographs and landscape interventions as collaborative. When I talk about these as ceremonial, I’m not going to tell you what the ceremony is, but I will tell you that the objects and materials that I'm working with are very important, and meaning can be built there.

One of the images from the Ceremonial Interventions series, To the Land of the Dead – Shiishonga (2018), depicts a spider web that looks like a black hole. That’s a portal I made in collaboration with a spider. These works are always a response to the landscape, which attunes you to seasonal shifts and movements of animals through a space...those kinds of presences that are left. The materials are really important because I carry them with me to these places not knowing what they’ll turn into, or what arrangements will happen.

When collaboration has come in in other ways...it’s never super comfortable, which I appreciate. For the Autry piece, I was on a plinth all night, taking pictures of people with an instant camera. I asked them to tell me what home was. I thought I was going to build a coordinate point map, but instead it became a constellation of sentiment around ideas of home, which was really beautiful. For my project at Grand Park in Los Angeles, Wee Nehiinkem—All my Relatives, Nechoova yakeenax—Dance with me, Taamet’e Pakook—The Sun is Rising (2020), I did a lot of consultation with community members. The project was public-facing; it was about monumentality and the removal of the Christopher Columbus statue two years earlier, so the gesture of it was really to serve the Tongva community. Cindi Alvitre, who I very much respect and love working with, also did a component part for that project, so we worked together to create that space. Most recently, working with the architectural designer Liliana Castro on Pulling the Sun Back – Xa’aa Peshii Nehiino Taamet (2021) at the LA State Historic Park was a different kind of collaboration, where I had to let go a little bit of the formation of the work. We had these amazing conversations and she built this structure that was exactly how we wanted it to be, but it wasn’t imposing or enclosed in ways that I’d anticipated. It just came together.

JD: The Grand Park project you mentioned was considered a temporary monument. You also recently made Portal for Tovaangar (2021), a virtual monument to Tongva land, as part of a collaborative initiative between the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and Snap, Inc. These works address multiple timescales simultaneously--they connect the “here and now” of their viewing experiences with histories and imagined futures of Tongva communities and lands. How do these projects respond to and expand on preexisting understandings of monumentality?

MD: Monumentality first came into my work in formal language in the Grand Park project, which was a direct response to the removal of a Christopher Columbus statue at the site in 2018. When I was asked what I might make, my first impulse was to imagine Toypurina, the Tongva woman who tried to lead a revolt against the Mission. I was thinking about what you do in your stereotypical “on a pedestal” kind of monument, like the Columbus statue. With this coding, your immediate response is to pick that important person, put them up, and make them important. But that’s a projected version of history, but it’s not “the history,” even if there could be a “the history.”

What do I look up to? Who do I look up to? What are the things I want to elevate? For me, monuments tell a story, but as important as Toypurina’s story is, I realized that’s not what I wanted to do. I think a lot about ancestral connection, and in that, there’s this sophisticated understanding of being able to position and understand seasons, time, and position in the world in response to astronomical movement. I knew this story about how the celestial bodies of the Pleiades and Taurus came to be. It’s a beautiful story about sacrifice, selfishness, love, and connection. The Grand Park project was about that kind of storytelling, about pointing back to ancestral knowledge, sophistication around technology, positionality, and attunement. The plinth at the bottom was the Pleiades and the tarps above were Taurus, so there were two constellations. The sun was meant to beam down onto the plinth through cutouts covered with gels. The light was making the connection between those two constellations, which happens in the story, and they’re also physically located in the sky in proximity. It didn’t line up perfectly, but it was really a moment of possibility.

What makes me excited about ideas of monuments is pushing forward into possibility while pushing against a singular place, time, or person. For this piece I was thinking about grandeur, modes of looking, and the viewer’s posture in response to a reference point that maybe isn’t about an institution.

JD: This institutional point strikes me as relevant to Portal for Tovaangar, which straddles virtual and physical space on LACMA’s campus. Historically, the museum’s space for monumentally-scaled works has skewed towards white male artists, including Chris Burden, Richard Serra, and Michael Heizer, whose Levitated Mass (2012) is adjacent to where your work is sited. Can you tell us about the process of creating this work, why you chose to locate it at the museum, and how you see it operating in the context of LACMA’s other “site-specific” works?

MD: As for placement, it was a little about taking up space and being present--being active and activated, but not in a historical, artifact sense. There was an overlap of presence for me at the site: LACMA as this huge cultural institution has a certain weight to it, then there’s this knowledge of the site that I have in a cultural way, then there’s this family history of my dad being there, and talking about the remains that were taken from that place, and his work in repatriation, and how that’s looked at. There was the proximity to the Tar Pits, which was an important site that was used for Tongva ti’ats, which were the plank canoes that went out to Pimu (Catalina Island). There was also Levitated Mass, this huge boulder suspended over a pathway that was very much in proximity. What does it mean to levitate star stones next to this other piece? What does it mean to have something that is seen only in a virtual mode versus something that you can’t escape the presence of? It’s a charged space and there was definitely an intention of presence.

I also painted a canvas and made a sculptural arrangement for this monument, which was confusing to people, but I wanted to document it in the site...take it to LACMA, put it out on the ground in a physical way, and spend a day there photographing it so the same light hitting it would exist in the app. This project was a really great opportunity to do things that I couldn’t do in the physical world, like have salt float into the sky, and move stones up into the air. You could also walk inside of it. You probably couldn’t do that anywhere else--be inside, look up, get on top of it. Be immersed.

There were other things that came out of Portal for Tovaangar that I’m really proud of, too. Deliasophia Zacarias, the Snap Research Fellow in the Director’s Office who I worked with, wrote a really beautiful post for LACMA’s Unframed blog that gave more context for the project. I also worked with the Education team there to create a podcast series. I talked to Ed Krupp, the director of Griffith Observatory, Dr. Wendy Teeter, Curator of Archaeology for the Fowler Museum at UCLA, my father Robert Dorame, and my cousin Megan Dorame reads a selection of her poetry. It’s a really beautiful series with conversations that go into the layers of history, time, and experience in this particular space in a broader context of Los Angeles. It’s always my hope, when I participate and engage in these projects, that they spark some interest and visibility and understanding that leads to more Indigenous representation in general. Those conversations were really amazing and for me, that’s the permanent part of the project.

JD: Maybe we could segue from talking about Portal for Tovaangar to portals more generally, which have continually emerged across your practice. They appear in your photographic work, like in To the Land of the Dead – Shiishonga, which you mentioned earlier. These ephemeral interventions evolved into constructed installation works that include what you’ve called micro-constellation portals. Can you explain how you conceptualize portals in your work, the multiple ways in which they operate, and what kinds of movement they allow for?

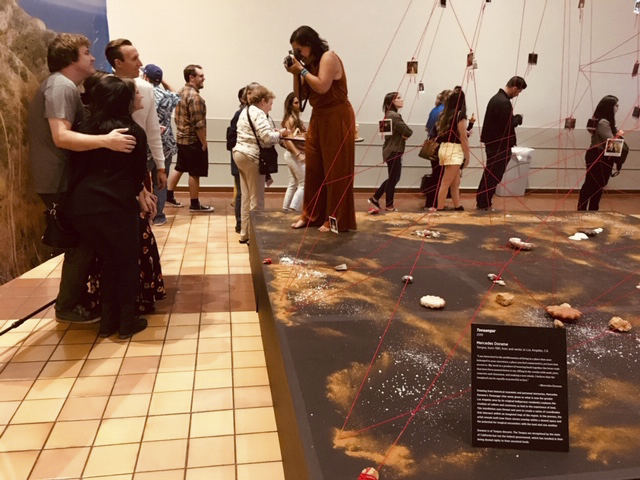

MD: I think...I had been working with this motif of the portal for a long time and maybe not naming it. That’s why I say To the Land of the Dead – Shiishonga, the collaboration with the spider, would be my first portal. That was earlier on, predating the installation at the Hammer Museum by months. The piece in the 2018 “Made in LA” exhibition at the Hammer was titled Orion’s Belt—Paahe’ Sheshiiyot—a map for moving between worlds. In Tongva cosmology, there are layers of worlds, and the ceremonial space is that place where we’re able to make transitional moments and move between them. That’s why I map the constellations, and why they’re heavy, and concrete, and exist on a plane in my installations. When I was thinking about the star stones for the Hammer piece, they became these anchor sites or anchor maps for how to get back when you go out.

The soundtrack of Portal for Tovaangar includes recordings of my ancestors made from wax cylinders that are held in the Smithsonian. That’s one voice. You have my voice in there. You have ambient sounds from crows that root you in the here and now, and my daughter sings on it, too. A lot of times ideas of portals, time, and space also exist in generational experiences. Moving between worlds is sometimes about talking to somebody who had been in that space fifty years ago or thirty years ago, or the stories my dad told me about walking there with his father, as a kid. In my earlier years, when I wasn’t supposed to talk about beauty, nostalgia, memory, or intuition (which were these unspoken rules in grad school), I would never have been talking about ceremony, or ancestral connection, or feeling attuned to things…now I’m open and acknowledged it as a mode of research and query that I take seriously.

JD: I’d like to talk in a little more detail about the aesthetics of verticality and levitation present in your portals and micro-constellations. In addition to some of the works we’ve already discussed, you recently installed Our Land and Sky Waking Up - ‘Eyoo'ooxon koy Tokuupar Chorii’aa (2021) at the Fowler Museum and Ancestors Leading the Stars - ‘Eyoohiinkem He’uuk Shishyoota (2021) at the Begovich Gallery at Cal State Fullerton. You use lengths of red string to elongate your installations, mapping your engagement between land and sky and implicating the body of the viewer. Sometimes this happens in a gallery, where you’re acknowledging and responding to architecture. Sometimes it’s outdoors...a different kind of architecture that’s about the building up of public space, public land, Tongva land. The string encourages viewers to look up and down, to develop awareness of Indigenous space as both terrestrial and celestial. Can you talk a bit about this?

MD: In its elemental idea, the red string is about the same positionality that I was talking about in relationship to monuments. Sometimes we forget to look up, we get so wrapped up in things. Like, today is a new moon...do you know what phase the moon is in? There’s an element of paying attention to those kinds of moments and understanding their bigger scope. But, it’s not just about looking up, it’s also about following that line back into the land, which speaks to the idea that you brought up about public space being Tongva land. Do you know where you are, really? The Tongva were caretakers of this land for thousands of years before the last two hundred years of occupation. Thousands of years. From a distance, my installations do kind of have this micro-constellation, portal, night sky feeling, but as you get closer, those objects become more indecipherable instead of becoming more deciperable. They point to understanding as continual engagement, connection, history, context...kind of a push and pull.

JD: Your sculpture in LA State Historic Park, Pulling the Sun Back – Xa’aa Peshii Nehiino Taamet (2021) combines elements of Tongva community structures of home, healing, and ceremony to address spatiotemporal continuities of Indigenous existence on and in Tovaangar landscapes. So much of what we’ve been talking about—formal aspects of your work, phases of your career, your work’s thematic breadth—they all come together in this piece. When I saw it, I was reminded of something that was so poignantly gestured to in the Tonvaangar episode of Netflix’s City of Ghosts, in which you starred: in the absence of recognition by the federal government, Tongva communities lack access to tribal lands. With no officially designated spaces, public parks have at times been some of the only places available for ceremony and other gatherings. I wanted to ask you to tell us about the structure and layout of this sculpture, its status as a public artwork, and what relationships it has to its surroundings.

MD: Pulling the Sun Back takes you into a movement of working through space, ideas of alignment between the sun and shadows. The oculus sits over the plinth, and that crux is a ceremonial arrangement. There was also a relationship between the sculpture and the oak tree nearby; it became really important as a grounding moment in the scale and orientation of the project. I incorporated some of the acorns from the tree, and some of the flowers, and some leaves that had fallen as a kind of offering and recognition of the space.

The installation doesn’t feel ephemeral, but it’s kind of an ephemeral piece--it’s rebar, river rock, canvas, and paracord material. In a full-circle kind of way, the canvases also reference the photograph because I’m still working with the negative. I make them by putting tape down to create a negative space, and then impose pigmentation on top of that and remove that negative, and that creates the image. I like the idea that the wind, rain, and sun will have an impact and leave their own mark on the piece as well. It’s also kind of beautiful that people have started leaving things...little random, strange, unexpected things. I think this speaks to the work having a feeling of openness; it becomes another collaborative moment.

When I started talking about land and having space to have ceremony or to rebury our ancestors, that’s not controlled, sovereign land. That’s a missing component for Tongva communities, but what fills in for that are these public spaces. I remember having conversations with the creators of City of Ghosts, and they asked where would make sense to me as a setting for the Tonvaangar episode. I said I go to Griffith Park a lot and I walk along the LA River a lot. Those are the spaces where I have these moments of reconnection, so they become very important. These public parks are the spaces that we have left, that we have access to. That access is bookended by regulation, so it’s contingent access...but these are our sacred spaces. Working on Pulling the Sun Back in LA State Historic Park...I liked taking up that space, claiming it, and inviting the Tongva community and the broader community to engage in that kind of understanding.