In the previous two essays for this series, I examined how the historical record is constructed through active erasure, and probed at the radical potential that imagination holds for charting black cartographies of freedom. Yet contestations over collective memory extend far beyond recognizing absences and doing imaginative work. Sometimes, counternarratives are documented all around us.

“Los Angeles is a city of conquest,” historian Kelly Lytle Hernandez writes in her most recent book, City of Inmates.1 In attempting to trace how Los Angeles came to be the incarceration capital of the nation, she was confronted with a research dilemma: how could she examine the history of incarceration in a city whose policing institutions had systematically destroyed their own records for decades?

Her methodological intervention, the “rebel archive,” suggests a way forward. In trying to uncover the history of mass incarceration in Los Angeles, she turned to “the words and deeds of dissidents,” whose far-flung records documented more than a century of resistance to human caging.2 She weaved together the scattered fragments of evidence, which ranged from scribbled notes to Congressional testimony. By looking beyond repositories maintained by the state, she expanded the scope of her evidence and critically analyzed different perspectives on a single social institution. She presents a forceful argument, backed by extensive research that spans two centuries: mass incarceration in Los Angeles is the outcome of the eliminatory logic of settler colonialism. Her conclusions ultimately rely on the ongoing struggles that targeted communities have sustained against a violent and repressive state.

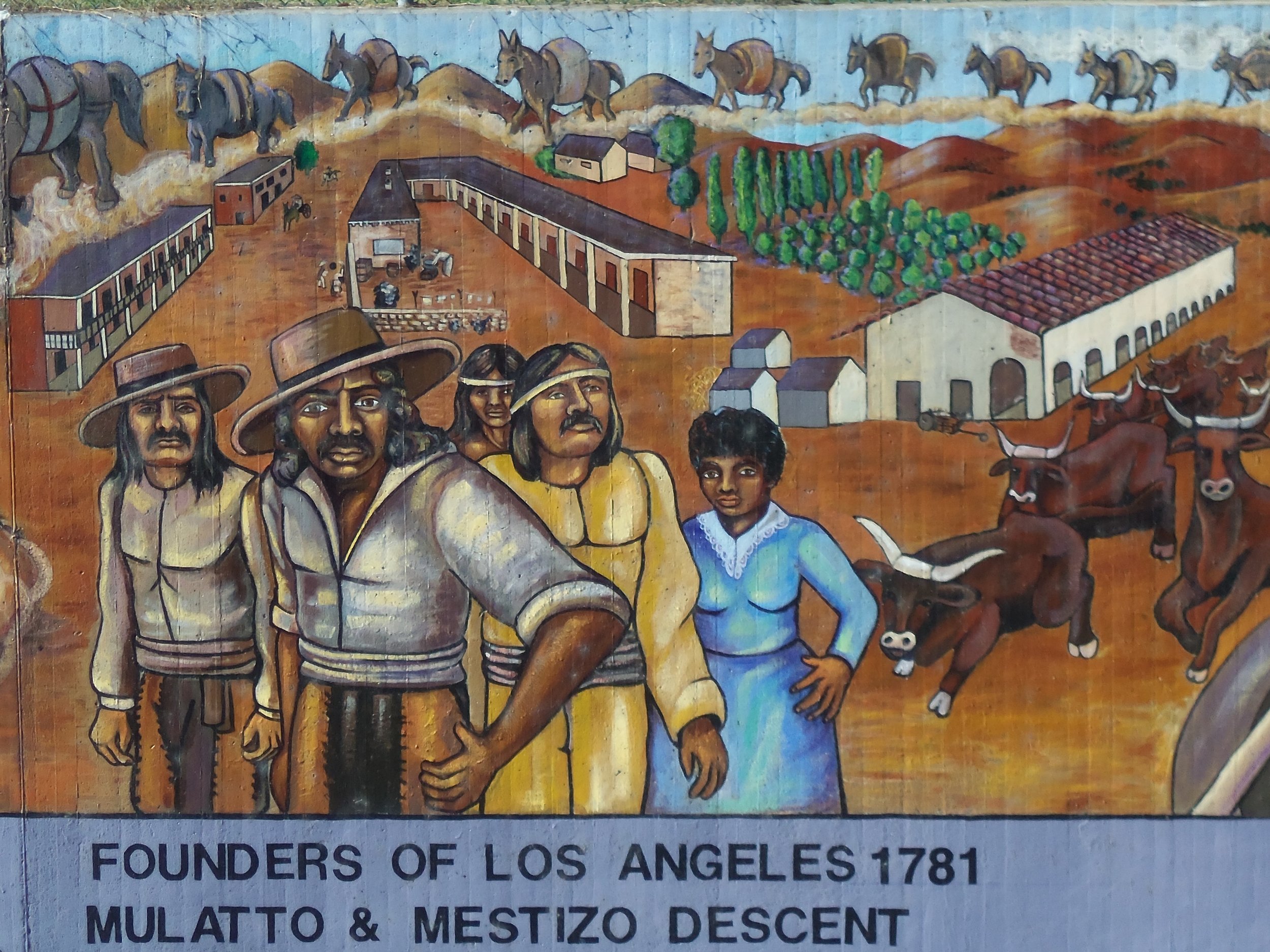

Photo of panels from The Great Wall, 2019. (Photo by author)

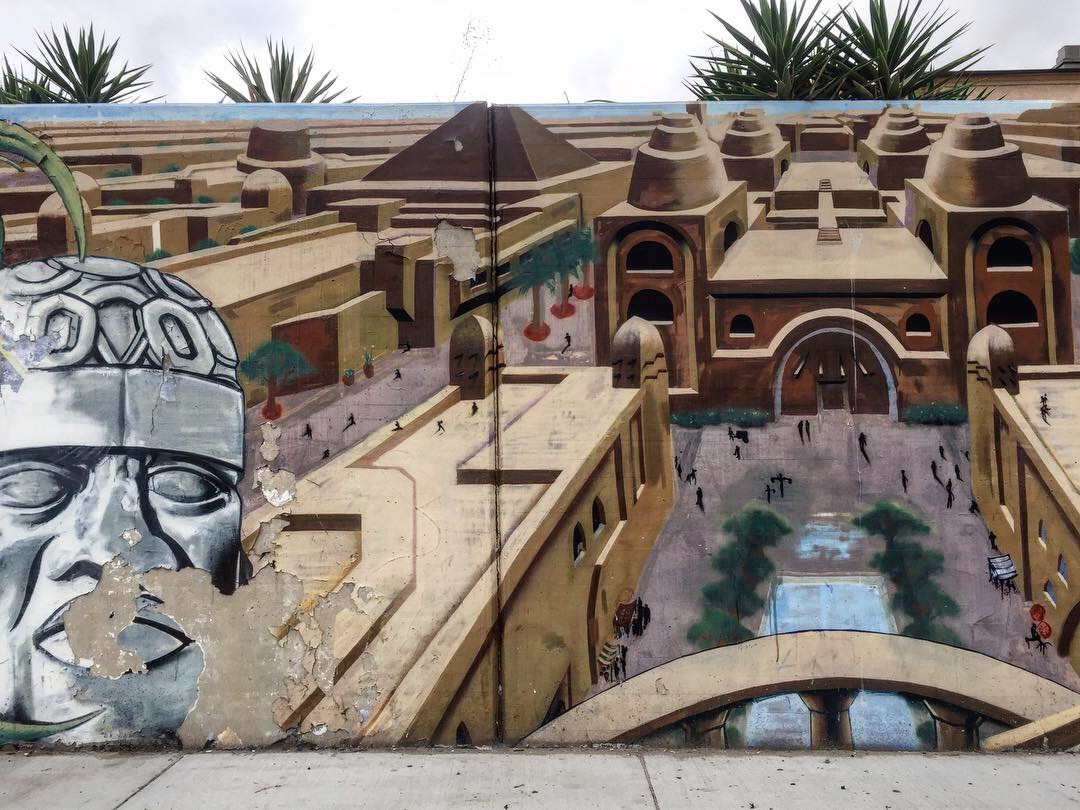

Like Lytle Hernandez, muralist and scholar Judy Baca foregrounds conquest and struggle in her study of Los Angeles. The Great Wall of Los Angeles, pictured above and below, is the product of the participatory efforts of more than 400 local teenagers, who worked collectively over several years to create a visual narrative of the multicultural history of Los Angeles.3 Mounted alongside the retaining wall of a concrete channel in the San Fernando Valley, the mile-long mural was begun in 1976 and is thought to be one of the longest in the world. The panels are organized as a timeline, starting with the prehistoric era and then tracing the Native communities who have inhabited the land for millennia. Significantly, the muralists framed the colonial encounter dualistically: indigenous perspectives of colonial conquest appear adjacent to the myth of discovery. The mural subsequently follows this contrapuntal reading, and is heralded today for its attention to the obscured dimensions of the city’s history: labor organizers and community activists appear alongside global icons, and histories of violence, including lynchings, housing discrimination, and mass deportations, are framed as events that shaped local life as significantly as the development of the film industry. The Great Wall, then, is a monument: not to silencing, but to the power of subaltern narratives that are preserved and shared despite ongoing suppression and threats.

Kaelyn Rodriguez, a PhD Candidate in Chicana/o Studies at UCLA, researched The Great Wall for her master’s thesis and supported its cleaning in 2015. In her research, she framed the participatory creation of the mural by the team of predominantly low-income teens of color as a monument in its own right. In an interview for this piece, Rodriguez observed that “Judy single-handedly organized this effort to work with youth who would have otherwise been a part of the juvenile justice system, because they were already on the road to incarceration… She was able to convince other folks in the city and say, ‘instead of putting these kids in a detention facility, give them to me for the summer.’” As the teenagers worked together over multiple summers on the mural, Judy brought in historians, artists, dancers, and poets to work with them and teach them the history.

Photo of panel from The Great Wall, 2015. (Photo by Kaelyn Rodriguez)

This collaborative ethos brought together people from very different backgrounds. As Rodriguez notes, “this was L.A. in the ‘80s, when there was a lot of racial tension. But no one got stabbed on the project, you know; there might have been fights, but Judy was a force and people respected her and the work. For me, that is part of the amazing legacy of this project—all of the people who participated in making the mural.” In a recent reflection, participant Ernestine Jimenez similarly characterized the creation of the mural as a transformative experience. Not only did these 400 Angelenos craft a larger-than-life counternarrative of the city, they continue to carry these histories and transform collective memory by sharing these stories with new generations.

The Great Wall is celebrated locally as a foundational corrective to whitewashed myths about the City of Angels, yet hundreds of such works of public art are scattered all over the city. Across town, “Our Mighty Contribution” tells a different story. The mural along a wall on Crenshaw Boulevard connects black struggles in the U.S. to African history, Afrofuturist dreams, and global black consciousness. While murals have adorned the Crenshaw Wall since the 1970s, “Our Mighty Contribution” was created in the early 2000s by RTN (Rocking the Nation), a collective of graffiti artists.4 Heroic figures like Frederick Douglass and Marcus Garvey are depicted, as are the pyramids of Kemet and soldiers of the U.C. Colored Troops.

Photo of panel from Our Mighty Contribution, 2019. (Photo by author)

These icons of black history are not directly connected to this city, yet the mural is deeply embedded in place, for it monumentalizes South Los Angeles as the heart of black life in the city. The mural draws references from across time and space to assert Crenshaw’s role as a diasporic anchor. In a city whose black population has dropped precipitously since the 1990s, this is a bold territorial claim. Land claims in black American communities are continuously threatened by structural forces, ranging from eminent domain to eviction; as a result, argue sociologists Marcus Anthony Hunter and Zandria Robinson, black senses of place are at once rooted and mobile.5 For people in search of the black community in Los Angeles, the references enshrined in “Our Mighty Contribution” unambiguously announce that they have arrived.

As geographer Laura Pulido reminds us, “all living things that pass through a landscape leave a trace—an energy if you will—that inhabits the land. Just as individual trauma rests in the body, collective trauma rests in the land, even when it’s rarely visible and in the everyday landscape, due to our heavy investment in denial.”6 The state’s investment in denying and erasing its own violence is heavy indeed, but valuable records of the rebel archive lay all around us, if we know where to look.