Le Marron Inconnu de Saint-Domingue, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Sculptor: Albert Mangonès, completed in 1967. (Kristina Just, 2012)

How are we facing the void of black monuments?

In our national conversation on the power that Confederate monuments hold in public memory, there is one dynamic discussion that has fallen off the radar. Last summer, a robust Black Twitter conversation emerged about statues found throughout much of the African diaspora. The discussion started through a single observation made by Samuel Sinyangwe, a policy analyst and data scientist who uses data to fight police violence for the Mapping Police Violence project: “First day in Barbados and we drove past this monument three times. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Screenshot of the initial tweet by @samswey in the slave rebellion monuments discussion on Twitter, July 1, 2017. (Screenshot by author)

What followed was a cascade of photos and recollections as hundreds of people shared their encounters with these statues honoring the rebellions of enslaved people from Brazil to Benin, and all across the Caribbean. Scrolling through the seemingly endless stream of tweets and absorbing these commemorations of black freedom made their absence in the continental U.S. all the more conspicuous. A refrain quickly emerged as many commented from the U.S.: we don’t have that here. While the National Park Service draws from the landscape to reinscribe histories of enslavement into public consciousness at several sites of conscience, including Philadelphia’s President’s House and Maryland’s Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park, these places evoke a different understanding of black freedom than prominent statues of rebellious people breaking free from bondage. These few National Park Service sites do the important work of contextualizing freedom seekers in the landscapes of their lives and challenging national narratives of democracy and liberty, but the numerous monuments to black liberation scattered elsewhere in the diaspora reflect their histories of decolonization: they assert the state’s support for overthrowing systems of subjugation. This Twitter exchange was a digital moment illuminating what UC Berkeley English Professor Nadia Ellis deems the “territories of the soul”: a queered diasporic recognition of elsewhere, a space where one belongs, yet which remains elusive.1 She draws on the work of the late theorist Jose Esteban Muñoz to conceptualize this space as a horizon of possibility, where one is aware that the point of fixation is beyond reach.

The Black Twitter conversation illuminates the painful resonance of our ‘missing monuments’—those histories too disruptive to our national myths to be commemorated by the state. In the years following the Civil War, Robert E. Lee himself opposed the creation of Confederate monuments, yet as of this writing, more than a dozen busts and monuments honoring his service as a Confederate commander stand all over the North and South, including one that remains on view inside the U.S. Capitol. There has been ample conversation about tearing down Confederate statues, but what of the void that we've all been living with for centuries—public commemorations of black resistance?

Good Hope Baptist Church, Culpeper Virginia, August 26, 2018. (Photo by author)

Good Hope Baptist Church is located on the outskirts of a small Virginia town, nestled in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. My ancestors lived on this property for generations; initially as property themselves, when they were enslaved by the Bowen family, and then as free people. While my branch of the family made their way north around 1900, some members remained in place. They founded this church on the land, and their descendants continue worshiping there today.

The public monuments that tower over traffic circles and market squares throughout the Caribbean inspire awe and reverence as they remind passersby of a proud history of resistance. They are the products of state support and public funding. This church is not like that. This church is located in a county whose statues honor its Confederate soldiers rather than recognize that a majority of its residents were enslaved in 1860 or commemorate its black freedom dreamers who walked off the plantations and emancipated themselves during the Civil War. This church exhibits none of the defiant, rebellious spirit possessed by the statues of El Yanga in Mexico or Le Marron Inconnu in Haiti, and yet there it stands: tucked away on a country road, neatly painted, steeple thrust toward the sky, expressing a quieter sort of freedom. Good Hope Baptist is a monument to the reclamation of a homeland. It is a testament to the capacity of faith to sustain endurance. And, in a once hostile territory, the establishment and continuity of this church, in this place, is a territorial assertion in its own right. As Kevin Quashie observes in The Sovereignty of Quiet, resistance is a significant aspect of black articulation, yet as a concept, it does not encapsulate the fullness of expressions of black humanity. An aesthetic of quiet enables what he terms “a sweet freedom: a black expressiveness without publicness as its forbear, a black subject in the undisputed dignity of humanity.”2 Not all monuments require public recognition. Some, in the grace of their intrinsic practices, simply are.

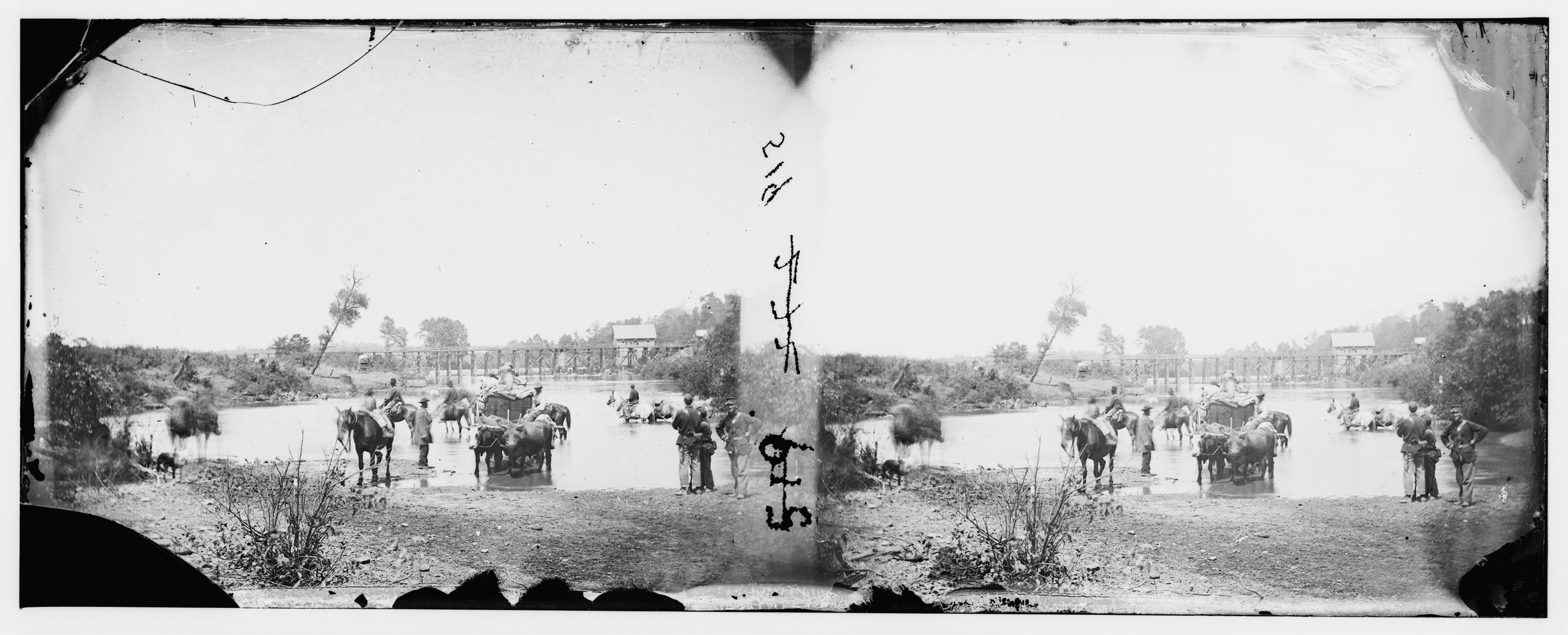

Self-Emancipation: Timothy H. O’Sullivan, Rappahannock River, Virginia. Fugitive Negroes Fording the Rappahannock (During Pope’s Retreat). Timothy O’Sullivan, August 19, 1862. (Library of Congress)

This year, in a series of essays for Monument Lab, I will situate monuments – the missing monuments, as well the obscured, the everyday, the spectacular, and even the speculative ones – within the discourse of black geographies. Thinking through the distinctions between voids of erasure, like the missing monuments of black resistance, and quiet, as seen in the endurance of the inward-oriented sanctuary, raises important questions of the legibility of landscapes and the centrality of displacement. In her pivotal work Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle, Katherine McKittrick develops the framework of a black absented presence, through which she suggests that histories of violent spatial erasure can be resurrected and made livable through a different sense of place.3 I argue that monuments inscribe meaning and possibility into our environments. By looking more closely at histories of black erasure and creation in the U.S., everyday sites might take on new significance and raise new questions. How are connections to place ruptured by, and sustained despite, processes of dispossession and displacement? How might ordinary places be as deeply imbued with a community’s values and struggles as any gleaming sculpture rising high above a boulevard? And how are people imagining and creating monuments anew?

As a scholar of planning history and urban geography, these questions are of great professional interest. Though I open this series with a reference to my own family’s histories, in the subsequent essays I will engage with the work of artists, activists, and scholars to discover how they are thinking about the communal production of public memory. What draws people together to fight for formal designation of an ordinary place, or organize and demand that statues should fall? And how do ongoing processes of black dispossession, through foreclosure, eviction, displacement, exclusion, and erasure, underpin these counter-hegemonic strategies of spatial remembering? As I sketch out the contours of my dissertation research, which will analyze black exurbanization and the community development practices of multi-located people, I will use this opportunity to think deeply and critically about the role of memory in black spatial practices. I look forward to sharing these thoughts with you.