Excerpted from The House on Lemon Street: Japanese Pioneers and the American Dream (University Press of Colorado, 2012), by Mark Rawitsch. Used by permission of the publisher. www.upcolorado.com.

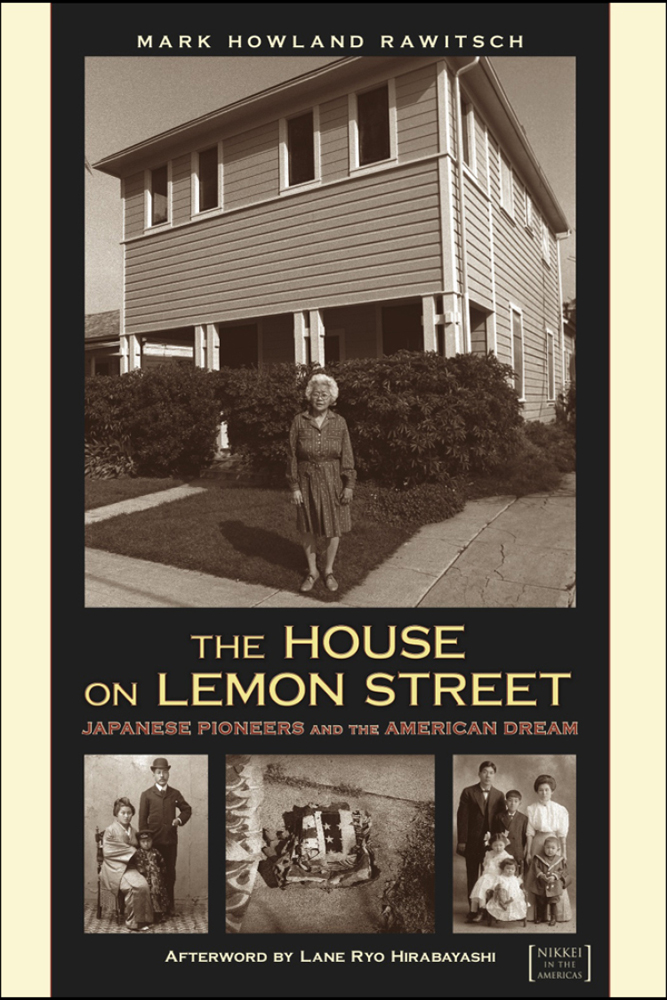

In recent years, efforts to identify and preserve American historic landmarks reflecting a wider vision of the past have begun to expand understanding of our diverse history. Harada House National Historic Landmark in Riverside, California, is one of those places. The purchase of the house in 1915 by Japanese immigrants Jukichi and Ken Harada led to the first Japanese American challenge to the California Alien Land Law of 1913. Its use in the late 1940s as a small refuge for homeless Japanese Americans returning from the forced removal of World War Two added to its significance. This excerpt from The House on Lemon Street: Japanese Pioneers and the American Dream by Mark Rawitsch (University Press of Colorado, 2012) sets the stage for the story of an American family facing great odds to triumph over prejudice and inch ever closer to realizing their own American Dream.

Although the God-fearing citizens of Riverside had over the years been more tolerant than many of their California neighbors, when the Haradas bought their new house on Lemon Street, the Golden State was still the place where some of its grandfathers had comfortably espoused the political campaign slogan “The Chinese Must Go!” Many more men and women in the American West were fretting over the growing number of Japanese immigrants, what had been termed the Japanese Question. And, as Cynthia Robinson’s Riverside newspaper had said earlier that year at the preview of motion picture director D. W. Griffith’s cinematic triumph The Birth of Nation, the entire country was becoming increasingly occupied with discussions of race and what many still called the “Negro problem.” If old Mrs. Robinson or any of her neighbors had been influenced by the disturbing images of director Griffith’s controversial motion picture master piece, Jukichi Harada’s plan to move his family to a nice house on Lemon Street might have made them think their neighborhood was in grave danger. Like the unnerving scene in The Birth of a Nation when black soldiers with rifles push a white man and his children off the sidewalk, to Cynthia Robinson and her neighbors living on Lemon Street the idea of a Japanese immigrant moving his family to the center of what the local paper called “one of the most favored residence districts of the city” was simply too much to bear.

Although the Haradas had already suffered one terrible setback when their second son died in 1913, they had made steady advancement over the last few years toward success in sunny California. Yet despite their progress, Ken had already pointed out to Jukichi that they might not succeed in a place that sometimes felt so far away from home to her. If they could just find a house of their own in a good neighborhood among other decent families, a healthier place than living downtown with transient roomers on the second floor of a rented boardinghouse, perhaps they could finally make a better home life for their children. Or so they hoped.

Within hours of Jukichi’s first visit with widow Cynthia Robinson, his new neighbor sounded the alarm that a Japanese family was coming there to live. In no time the turmoil bubbling around the Haradas’ new house began to spread. Jacob Van de Grift, the property broker who had not answered Jukichi Harada’s repeated requests for assistance, lived in a fancy Victorian home just around the block on Orange Street. He soon joined Mrs. Robinson and other concerned neighbors to form a committee to prevent the Haradas from buying the house on Lemon. Other influential people in town, however, sided with the Haradas. Before long, the State of California joined the fray, filing the first lawsuit against a Japanese family under California’s Alien Land Law of 1913.

After years of squabbling about the future of the Golden State, a place many had long regarded as White Man’s Country, and acting against the wishes of the nation’s leaders and others concerned about the emergence of Japan as a powerful player on the international stage, the state legislature had passed its first Alien Land Law in 1913 to halt Japanese advancement in California. When Jukichi Harada, a Japanese immigrant ineligible for American citizenship, bought the cottage next door to the widow Robinson, he landed his family squarely at the center of a social maelstrom that would not subside for another generation. In twenty-five years the battle for acceptance and equality of Japanese Americans as citizens of the United States and equal participants in the American Dream would lead to one of the most challenging and shameful events in all of American history, but in the winter of 1915, long before anyone had ever even heard of a faraway place called Pearl Harbor, the fight was just beginning.

As real estate agent Noble prepared the deed to the house on Lemon Street, he thought it unusual Mr. Harada had asked that ownership of the house be recorded in the names of his three youngest children. All were under ten years of age. The oldest of the three, daughter Mine, was only nine; her sister Sumi would turn six on Christmas Day; and her brother Yoshizo was just three years old. Unlike their oldest brother, Masa Atsu, who had been born in Japan before his parents came to California, the three youngest children were citizens of the United States because they were born on American soil. It was, however, unusual for Noble to record the sale of a house in the names of anyone so young. As soon as the deed to the property was completed and filed at the county courthouse, it took only a few days for Noble to hear that he and Mr. Gunnerson might be in some sort of legal trouble for selling a house to the underage children of a Japanese alien.

Worried about the possible consequences, Noble wrote a brief letter to California attorney general Ulysses S. Webb to find out more. Webb was the state’s chief law enforcement officer and one of the authors of the 1913 Alien Land Law, so he should know whether Noble and Gunnerson had violated the law. Noble asked Webb, “Can a Jap boy or girl born here in California acquire and hold real estate?” As Frank Noble awaited Attorney General Webb’s reply, others closer to home took far less time to respond. A week after Jukichi Harada purchased the house, regional newspapers reported that a local “storm of protest” was growing quickly into an issue of statewide interest. In a few more months other reports would claim that even the government of Japan and officials in Washington, DC, were closely watching the situation on Lemon Street.1

In its disquieting first review of the circumstances brewing in Riverside, “Land Titles to Children; Jap Plan to Evade Law on Aliens,” William Randolph Hearst’s Los Angeles Examiner said one Lemon Street resident planned to isolate himself from his new Japanese neighbors with a “spite fence.” Next-door neighbor Cynthia Robinson, it was claimed, intended to “plow up her driveway which leads to the rear of the Harada home.” Other members of the neighborhood committee soon developed more formal plans to oust the Haradas from their new house. Perhaps hearing rumors that hotelier Frank Miller intended to support the Haradas’ purchase of a new house, they soon hired Miller’s political rival, Riverside attorney and former state senator Miguel Estudillo, to represent them in a lawsuit aimed at evicting the Japanese family. At a meeting in Estudillo’s law office, neighborhood committee spokesman Van de Grift and attorney Estudillo tried once more to pressure Jukichi Harada to give up his new house. By then, however, Jukichi’s mind was set. He was not about to back down now. Van de Grift told of Harada’s refusal to accept their final offer, and the die was cast: “Mr. Estudillo made him an offer of $400 more than he paid, and he said: ‘I won’t sell. You can murder me, you can throw me into the sea, and I won’t sell.’”2