Planning has begun for the celebration of the Semi-quincentennial of the American Revolution, set to take place in Philadelphia in 2026—with a federal commission, sleek website, and a non-profit foundation arm to boot. But for many, the city’s 1976 Bicentennial doesn’t seem far gone. Relics of the Bicentennial survive across its host city of Philadelphia, if you know where to look. There are the faded American flag murals that dot concrete walls in the Riverwards; the Liberty Bell, ceremoniously moved on New Year’s eve out of Independence Hall and into its current public location for that year’s festivities; and the ‘76 emblazoned coasters, patches, and baseball caps that remain the desk drawers of those grandparents’ rowhomes that double as time capsules.

Harder to come by is evidence of the radical, 40,000-person parade that snaked through the streets of working-class North Philly on July 4th, 1976—a “people’s Bicentennial” that tells a very different story about American history than the spectacle of unfettered patriotism and kitsch that overtook the city’s downtown. It’s there, though, in the newspaper clippings and contact sheets that persist.1 These relics bring to life the radical syndicate, the July 4th Coalition, that took issue not with a particular policy issue, but with the Bicentennial’s progress narrative writ large, aiming to illuminate forms of American oppression that remained alive and well in the late seventies.

Police and protestors attendance at the July 4th Coalition protest parade, July 4th, 1976. Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA. Photograph by Joseph P. McLaughlin. Image provided by the author.

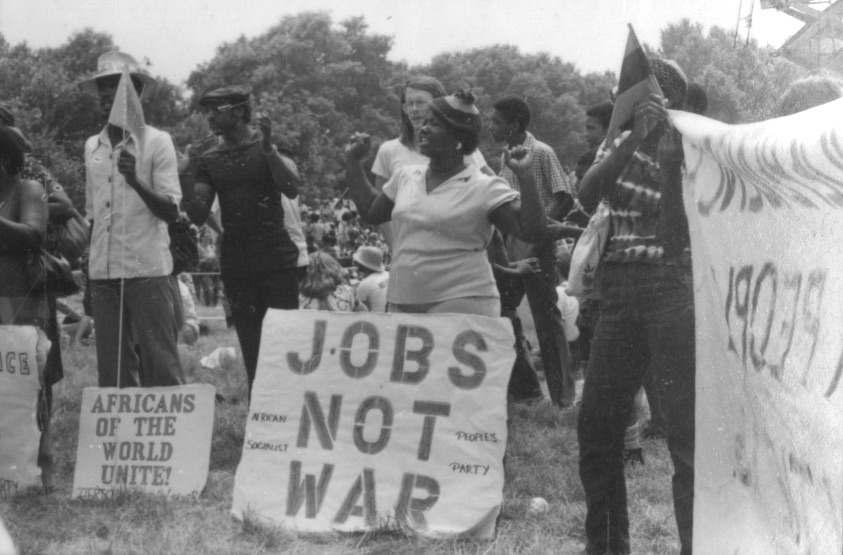

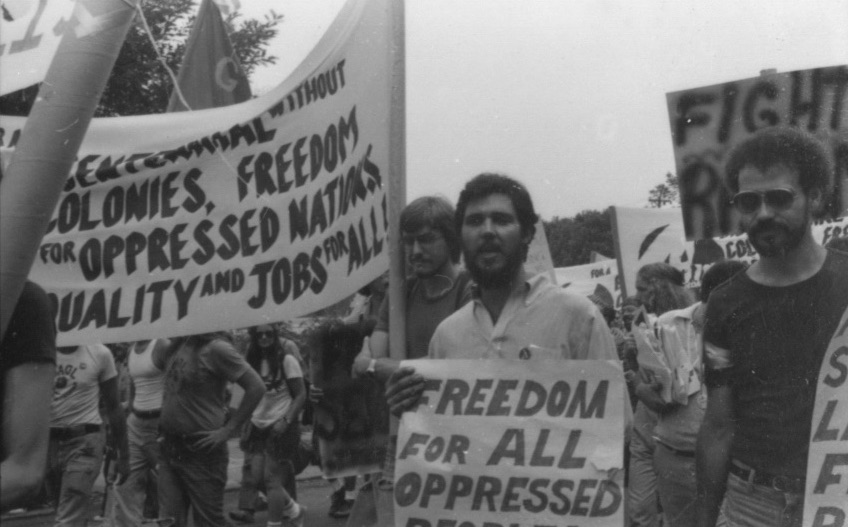

Puerto Rican socialists, Vietnam veterans, women’s rights advocates, Black liberation groups like the Black Panthers, and unemployed workers joined into one march that proceeded west along Lehigh Avenue and into Fairmount Park at Oxford Street, ending with a sprawling concert and cookout on the fairgrounds built for the 1876 Centennial. The sanctioned Bicentennial Corporation events (a parade on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, a covered wagon pilgrimage to Valley Forge, a large birthday cake) could not have stood in starker contrast to the counter-parade, which offered both a less rosy portrait of American history but—perhaps more so than the Bicentennial Corporation festivities—also offered an alternative future, a point of departure from the tired patriotism of the main parade.

Participants in the July 4th Coalition protest parade, July 4th, 1976. Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA. Photograph by Cathy Cockrell. Image provided by the author.

Reporters Mike Zielenziger and Rod Nordland described the protest in the Philadelphia Inquirer:

. . . the parade of blacks and whites, many of them in their late 20s and 30s went past. The group was accompanied by about 150 members of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Dressed in Army fatigues and marching in approximate formation, they counted cadence ‘One, two, three, four, we won't fight a rich man’s war’ as they walked by. The July 4th Coalition chanted slogans including ‘The people united will never be defeated,’ ‘No more broken treaties, no more Wounded Knees,’ and ‘Ho, ho, homosexuals, the sodomy laws are ineffectual.’ The July 4th Coalition’s numbers swelled during the rally in the park, where rock and folk music was featured in addition to speeches. Several busloads of police were near both demonstrations. There were, in addition, numerous legal observers from the bar association and other groups.

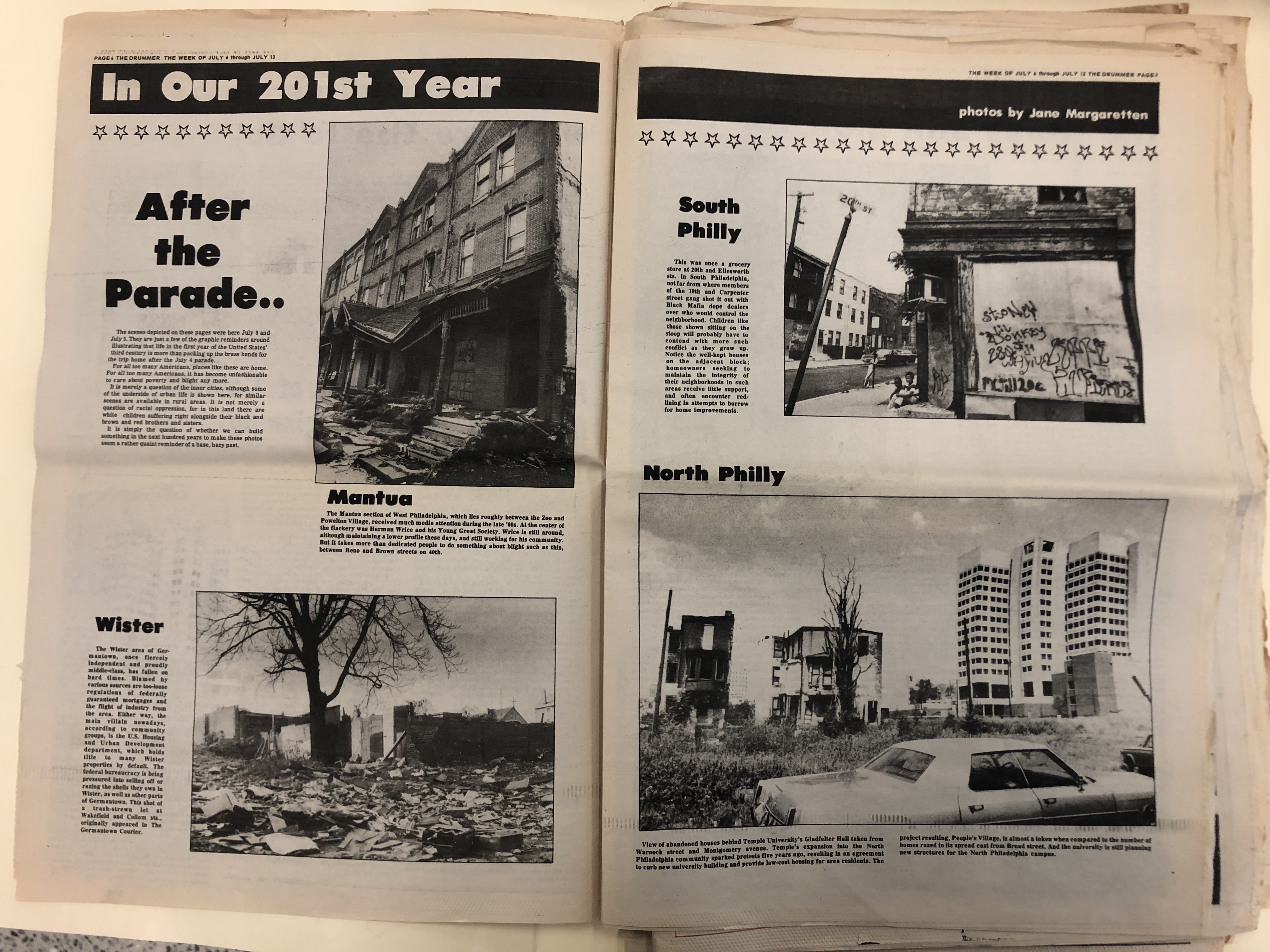

The Drummer (newspaper), no. 408, July 6–13th, 1976. Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA. Photography by author.

Summit on Dispossession

The protest came after weeks of fearmongering by Philadelphia Mayor and former police commissioner Frank Rizzo, who requested 15,000 federal troops to combat “a substantial coalition of leftist radicals” who he anticipated would violently disrupt the Bicentennial with acts of terrorism. Federal authorities rejected the baseless request, and the protest went on peacefully.

Members of the Dakota Nation participate in the July 4th Coalition protest parade, July 4th, 1976. Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA. Photograph by Joseph P. McLaughlin. Image provided by the author.

What seemed to strike out-of-town reporters covering the event was not its violence, but its proximity and relationship to poverty. The New York Times reported: “The march moved through the rundown black areas of North Philadelphia, where the windows of the abandoned buildings are covered with tin, indecipherable graffiti. Only one United States flag was seen on a drive of dozens and dozens of blocks through North Philadelphia.”

Participants in the July 4th Coalition protest parade, July 4th, 1976. Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA. Photograph by Cathy Cockrell. Image provided by the author.

Contained within this recounting of the July 4th Coalition parade is the unspoken shame of the Bicentennial: Philadelphia’s poverty—and the difficulty of feeling patriotism in its face. In what came to be known as the “Battle of the Bicentennial,” all sides—the establishment and the insurgents, the city and the protesters—instrumentalized urban decay and the daily trials of the city’s poor on the anniversary of the Revolution. Mayor Rizzo, for his part, hoped to use the Bicentennial as an opportunity to further criminalize poverty and assert control in the regulation and use of public space in an era thought to be defined by its lawlessness. After the uprisings of the late sixties and in the wake of the Vietnam War, the Bicentennial came at the right time for bureaucrats to assert an alternative to counterculture and disruption; they meant to reinscribe the values of family and patriotism that had been challenged in the preceding years. In contrast, the protesters understood the city’s fatal flaw not as its lack of order but as antagonism from an unsupportive state. A cover feature in , an alt-weekly newspaper in the city, from the week of July 6th, 1976 showed documentary photographs of the city’s poorest neighborhoods—Mantua, Wister, Point Breeze. “The scenes depicted here were July 3 and July 5,” the article read. “They are just a few of the graphic reminders around illustrating that life in the first year of the United States’ third century is more than packing up the brass bands for the trip home after the July 4 parade. For all too many Americans, places like these are home.”

Participants in the July 4th Coalition protest parade, July 4th, 1976. Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA. Photograph by Cathy Cockrell. Image provided by the author.

In some ways, the Bicentennial in Philadelphia became a summit on dispossession and disinvestment, with two conflicting answers: one, the official Bicentennial parade that strong-armed its way into obscuring these facets of the city, the other asserting itself purposefully in the margins, in the very spaces of poverty it aimed to cast light on. Indeed, by re-focusing the Bicentennial on the poverty of its host city’s inhabitants, the coalition seemed to ask: what does it say about the American Revolution that poverty, subjugation of women and people of color, and forms of imperialism remain so dominant in the United States? In other words, they asked the question that has preoccupied historians of the American revolution for decades: was the revolution really a revolution?

Historical Reenactment

The planning underway for the Semi-quincentennial in many ways recapitulates the Bicentennial’s original drama. While the federal commission plans nationwide celebrations, the local group Philadelphia250 has initiated a public process, through which everyday citizens can propose projects commemorating the anniversary of the revolution; 16 projects will be selected to receive substantial seed funding. While this gesture toward citizen-driven projects is admirable, it’s difficult to recognize the machinations of a foundation as a true instantiation of democracy. Indeed, while terms of debate from the Bicentennial are replicated in the Semi-quincentennial—namely around the question: what history will we tell about our country’s founding?—this time around, freedom has been replaced by the language of innovation; history has become more inclusive, but only as funding structures become less so. A once-public Bicentennial, funded and planned entirely within federal and local government commissions, has fifty years later been transferred to the anti-democratic private sector. On the anniversary of American democracy, it seems celebration, monument, commemoration, and history have met the same sorry fate as so many other functions of the state.

Participants in the July 4th Coalition protest parade, July 4th, 1976. Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA. Photograph by Cathy Cockrell. Image provided by the author.

Like all grassroots movements, the July 4th Coalition protest was not without its shortcomings. In particular, many accounts of the event recognize the awkwardness of tens of thousands of protesters, many from out of town, streaming through residential North Philly, where the neighborhood’s inhabitants—whose quality of life constituted the subject of the parade’s ire—seemed uninterested or frustrated by the disturbance. For its flaws, the parade nevertheless modeled a radical vision of democracy in a country that they felt had failed to meaningfully represent its people. The photographs of the event evoke a freedom—to express, play, and join in community—that is missing from representations of the explicitly patriotic events of the day, which more readily embraced the language of freedom. While positioned in opposition to a kind of flag-waving patriotism, the protest evoked the American founding in ways perhaps not entirely legible to the participants. Modeling an alternative society from the streets of Philadelphia, the July 4th Coalition reenacted anew the societal rebuilding figured forth in the Revolution. In other words, despite its radical tendencies, the July 4th Coalition did not abandon the American project outright. In a particularly mid-seventies political gesture, the parade articulated a new Americanness as it critiqued an old one.

Parade on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway during the Bicentennial, July 1st, 1976. Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA. Photograph by Joseph P. McLaughlin. Image provided by the author.

If all goes according to plan, the festivities in 2026 will do little to challenge democracy’s contemporary failures. In Philadelphia, where the Semi-quincentennial’s partner organizations include Comcast, Aramark, Penn Medicine, and Bank of America, the celebration assigns the power to commemorate to the same actors that already dictate much of the city’s identity and economy. Indeed, the Semi-quincentennial seems primed to swap out the Bicentennial’s traditionalist patriotism with a fresh neoliberalism—celebrating individuals instead of ideas, the leanness of the private sector rather than the representative possibilities of the state. Another approach, taking cues from the July 4th Coalition, might break from this status quo altogether, inscribing a new social order in the way only protest can.