A postcard showing the unveiling of the Confederate Monument, June 2, 1913. (UNC Libraries)

On August 20, 2018, the night before the first day of school, students and activists at UNC Chapel Hill came together—democratically, joyously, and raucously—to tear down the statue of Silent Sam, igniting a debate that quickly spread across campus and into the national spotlight.

Silent Sam is a bronze statue of an anonymous young confederate soldier, fashioned by the sculptor John A. Wilson sometime before 1909.1 Silent Sam originally stood atop a tall stone pedestal in the historic heart of the campus, McCorkle Place, bedecked in a fresh uniform and a jaunty hat with the brim pinned up on the right side. His nickname is likely meant to invoke Uncle Sam, the embodiment of American patriotic fervor.2 He holds a rifle, though his bayonet is sheathed.3 His cartoonishly large eyes give the effect of youth, spirit, magnanimity—a piercing, clear-eyed, heroic gaze. He honors the dubious claim that, at UNC Chapel Hill,

More than 1000 University men fought in the Civil War. At least 40% of the students enlisted, a record not equaled by any other institution, North or South. Sam is silent because he carries no ammunition and cannot fire his gun.4

Sam’s purpose is to honor and memorialize those many soldiers who fell in the Civil War, purportedly. However, make no mistake—Silent Sam was not erected to honor the Union student-soldiers. He is part and parcel of the argument Julian Chambliss makes in “Don’t Call Them Memorials.” Such a monument, as Chambliss redefines the term, is not a memorial, but rather a “‘political marker funded by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) and gifted to municipalities across the South to celebrate the reestablishment of white rule after Reconstruction.’”5 Silent Sam is precisely that. The United Daughters of the Confederacy gave Silent Sam to UNC Chapel Hill in 1909 in an overt effort to rewrite history in the name of white supremacy. And the university shelled out nearly four hundred thousand dollars a year to maintain this sculpture.

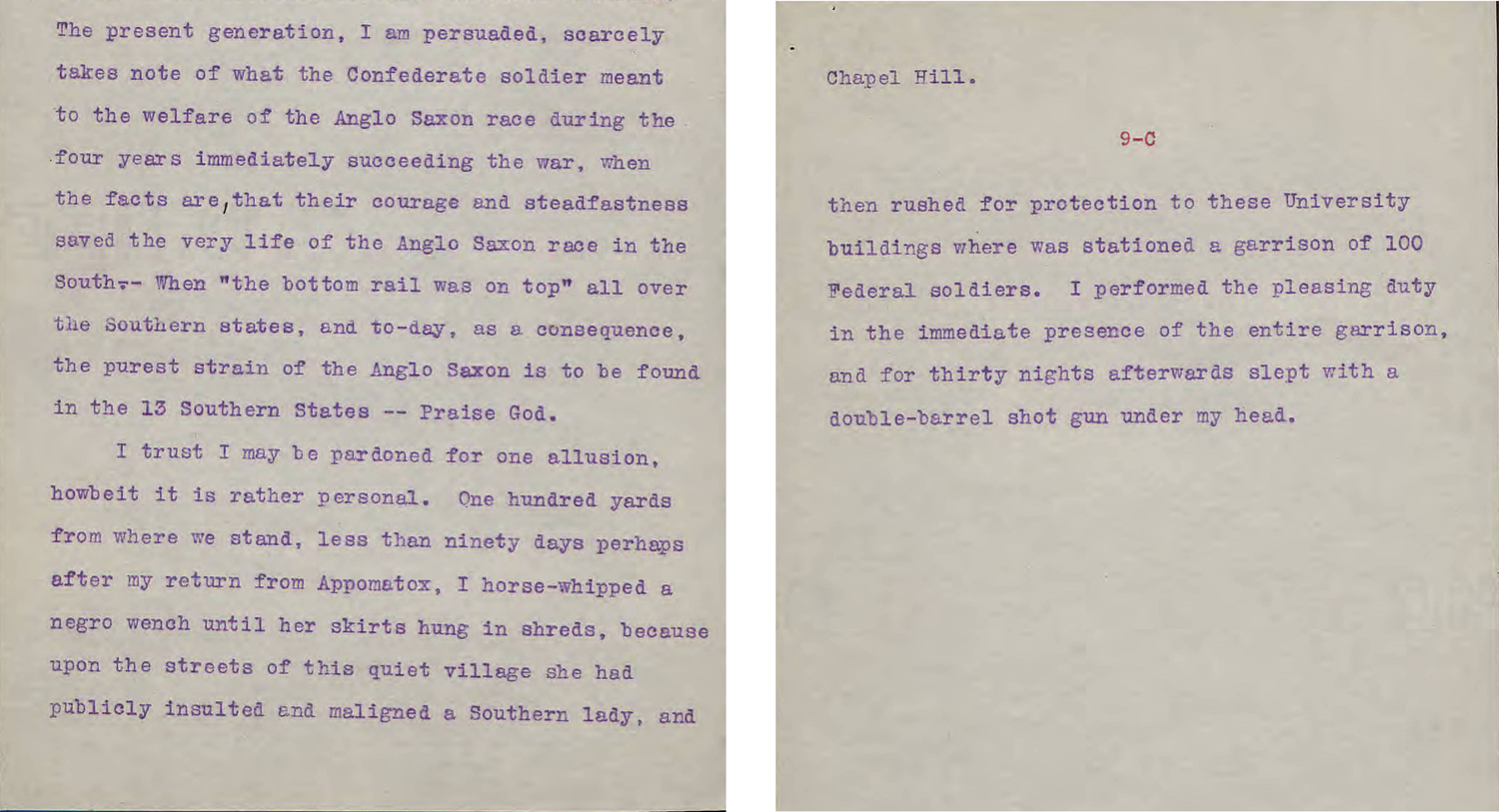

For any who might doubt the intent of the benefactors of the Silent Sam statue, consider the following excerpt from an infamous speech delivered on unveiling the statue. The orator, Julian Carr, was a slave owner before he became a Confederate soldier, and later an ardent supporter of the KKK. His harrowing 3,700 word panegyric to the Confederacy makes absolutely clear what Silent Sam represents:

Addresses, 1912-1914: Scan 104 & 105, in the Julian Shakespeare Carr Papers #141, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (UNC Libraries)

The full text of the speech is here. Historian Karen Cox notes the injustice these monuments impose on the people forced to live with them:

The stone soldiers who stand sentinel in southern towns pay homage to white heroes who were revered as both loyal southerners and American patriots, for their defense of states’ rights. Significantly, southern blacks, who had no stake in celebrating the Confederacy, had to share a cultural landscape that did.6

Not everyone forced to share this “cultural landscape”—what one historian calls a “landscape of denial”—would keep Sam’s silence.7 Four months before Silent Sam was finally toppled, Maya Little, a second-year doctoral student in History, smeared Silent Sam with a mixture of red paint, ink, and her own blood. Asked why she did this, Little explained:

The fact that Silent Sam stands there—uncontextualized, glorified, without our blood on him—needed to change. Adding blood to the statue is adding proper context. Because that’s what the Confederacy was built on. It was built on the blood of black people. That’s what Jim Crow was built on… My blood and the red ink symbolizing the blood of black people is context. To me, that’s the context for Silent Sam. The university doesn’t want that context.

Maya Little said the quiet message of the statue out loud, and for that, she was found guilty of a misdemeanor, and punished with eighteen hours of community service. Little wouldn’t let Sam be silent, because she recognized that the “silence” of Sam is his greatest power. Sam’s muteness makes it easy to overlook, seemingly benign—but to those who remember their history, it is an overt symbol of the persistence of white power, despite Confederate defeat. It is a celebration of the fact that Julian Carr was able to delight in whipping a human being nearly to death in sight of a Union garrison, and was able, fifty years after the fact, to proudly relay the story in a speech to a statue dedicated to that very cause. The silence of Sam is the silence of the Union garrison. It is the silence of the crowd listening to Carr’s speech.

Protests against the statue of Silent Sam on the Campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2017. (Martin J. Kraft/CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons)

When Silent Sam was finally ripped down from his pedestal, the administration at UNC Chapel Hill was forced to acknowledge the context that Little had highlighted in a rubric of her own blood. 8 Chancellor Folt convened a series of eleven hour-and-a-half long workshops over the course of a week of October 3-10th, attended by approximately 120 faculty, in an effort to canvas their collective wisdom for the sake of achieving some reasonable response to the felling of Silent Sam. Her efforts would ultimately topple her chancellorship. Their ninety-page report was made publicly available in late October. Shortly after, a UNC graduate student created the Twitter handle @now_what_sam, where she tweeted and re-tweeted the many faculty responses, ranging from thoughtful to ridiculous (see list below). Sam’s future was finally in question.

Relocate to outside of the Carolina Inn and have it hold a platter for serving cookies

Find a tree that was used for lynching, then bury the statue under it.

Curate the pedestal and treat it as a living thing; every year, a different artist rotates with a selection that has relevance and meaning

Return to the United Daughters of the Confederacy

Melt it down and make mini Silent Sam statues, if its meaningful to you, then you can own one for $9.95

DO NOT put it in a university library

Leave an empty pedestal.

Offer to President Trump.

Return to descendants of Julian Carr.

Bury the statue "in a process that never ends".

Auction the statue, use proceeds for scholarships (for African American students).

Sell tickets of $3 dollars each for a change for a blow with a sledgehammer to hit Silent Sam, then sell the resulting bits to raise money for reparation scholarships for NC African American students.

Sink in University Lake.

Give lump of metal to Elon Musk and Space X and let someone else do something with it.

Write obituary of Silent Sam, and notify his next of kin. 9

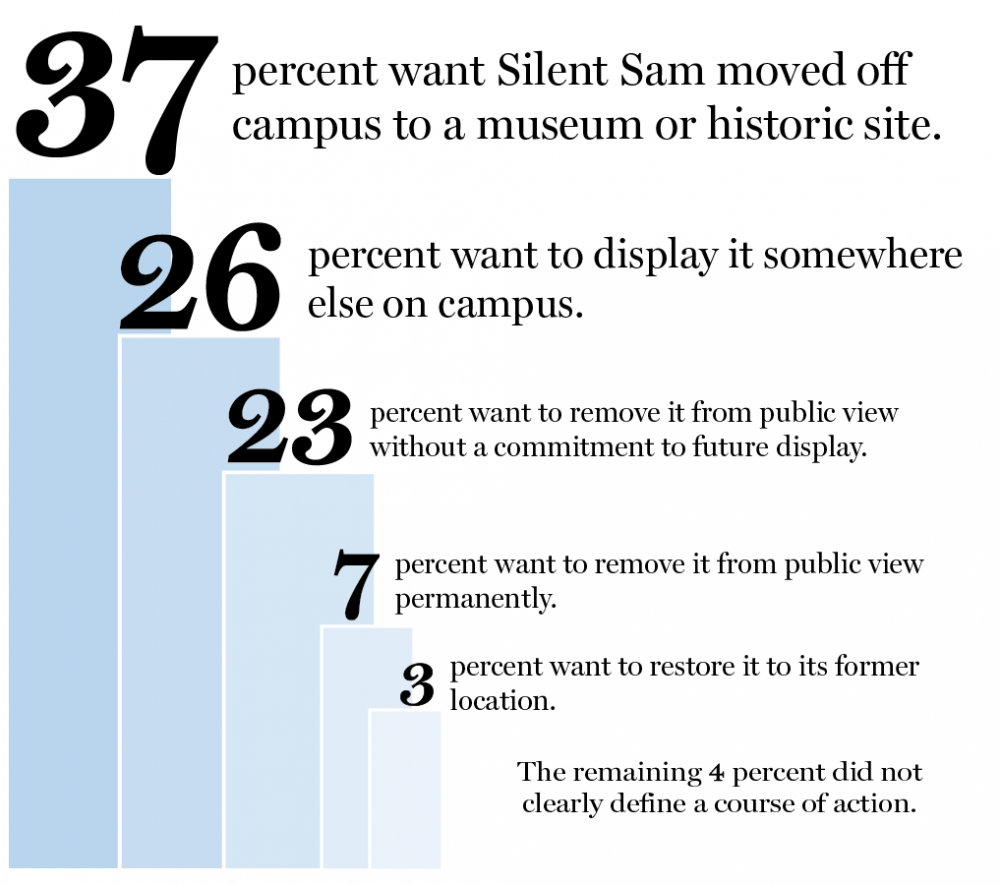

Concurrently, the Dean of the College Kevin Guskiewicz sent a survey to all 2060 faculty and staff at Chapel Hill, asking them what should be done about Silent Sam. Of the four hundred responses:

Screenshot of survey results, 2018. (Daily Tar Heel)

The survey revealed several epiphanies. One common thread is:

A surprising number of respondents claimed that studying the statue’s history convinced them it should not be returned. Many of these identified as white and Southern.

This point highlights the insidiousness of Confederate monuments: they are deliberately insinuated into public contexts, quietly. Without knowledge of who funded them, who erected them, the speeches that dedicated them, a well-meaning passerby could easily walk right by without any thought of what that handsome, clear-eyed “Anglo Saxon” statue is meant to signify. Silent Sam is not silent simply because he is without ammunition; he is silent because he is waiting for the appropriate audience to make him speak, a future audience of white supremacists. Until that audience returns, he silently waits. This is what makes his presence on campus so sinister: not just the past Civil War history Sam revises, but the future audience he anticipates.

Dean Guskiewicz’s survey took special pains to consider the eleven responses supporting the return of Silent Sam to his pedestal at McCorkle Place, though “none…presented a cogent argument for this action.” These responses in favor of returning Silent Sam fall into my taxonomy of Confederate Monument Apologism, particularly the fallacies of false equivalency, and erasing history. By contrast to those respondents for whom “studying the statue’s history convinced them it should not be returned,” there are those respondents who preferred not to review the historical record:

Some of the respondents who want Silent Sam restored to its old location gave credence to another respondent who wrote: ‘I am struck by the fact that those who demand, insist, and threaten that the monument be restored to its former place appear to have NO interest in learning about the intention of those who erected the monument.’ 10

Those who would have the statue returned are, at best, ignorant of the intention and purpose of the statue, or deluded by “Lost Cause” propaganda; at worst, they support Silent Sam’s racist worldview. The main takeaway of the survey is its conclusion:

We do not support the return of Silent Sam to our campus. 11

Sam lived out his long life for over a century as a marker of white supremacy at UNC Chapel Hill, a university funded by slave owners, built and maintained by enslaved people, and that did not accept black students until 1955. In what would be the last action of her chancellorship, Folt ordered Sam’s pedestal removed, effectively bringing the controversy to an end, though what to do with his corpse remains to be decided. White supremacy, however, is far from dead. It is nevertheless important to celebrate the destruction of any symbols of it.

The death of Silent Sam was a joyous occasion. One article describes how, "After the statue fell, jubilant protesters cheered, chanted, and embraced as the police looked on.” Confederate monument apologists tend to call the protestors a “mob,” but anyone who knows the history of Silent Sam, Civil Rights, American slavery, or civil disobedience knows better.

The joy reflects a maxim of the radical political activist Emma Goldman:

A revolution without dancing is not a revolution worth having.12

So long, Silent Sam—and good riddance!