In 2016, what was a Latin-themed dance night filled with joy and celebration ended in tragedy: 49 died and more than 50 others were injured by gun violence at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida. The very next day, guerrilla memorials grew on sidewalks, parks, and businesses as Orlando residents expressed their shock, fear, and grief. In the wake of the Pulse tragedy, there were three prominent locations in which people had begun to lay flowers and memorabilia in commemoration of the lives lost and survivors in recovery: (1) the green field in front of the Dr. Phillips Arts Center in downtown Orlando, (2) the “Orlando Health” sign in front a hospital where victims were being treated and (3) the Pulse nightclub itself. Of the three spaces, Pulse nightclub would ultimately become the site where individuals would continuously return for collective grieving; mounds of crosses, roses, pictures, and flags continued to grow around the site of the tragedy. Today, the Pulse nightclub is the site of an interim memorial, where photographs and ephemera are preserved and displayed across a winding, ribbon wall.

On one of my many visits to the memorial, this ribbon wall made me think: how does community consensus develop surrounding memorials of very recent tragedies? Who has the power to determine the narrative and placement of a memorial? And how is it shaped by the local community? The activity at the Pulse Interim Memorial can begin to tell us what it means to memorialize mass shooting tragedies.

Memorial-Making and Queerness

The Pulse nightclub transformed into an “official” site of memory in 2018, when Barbara Poma, the club’s owner, formed the onePULSE Foundation. Since then, the Foundation has leveraged local contributions while rallying national attention and funding. Moreover, the Foundation worked closely with the Orange County Regional History Center to assure local residents that their contributions to makeshift memorials would be preserved, curated, and displayed on the ribbon photography wall.1

The Foundation states that there are currently 200-300 visitors a day to the Pulse Interim Memorial. But there is an underlying tension regarding who the Interim Memorial is commemorating-- queer people in Orlando? For LGBTQ+ people of color? For the victims of the mass shooting? And to what extent can a memorial, something concrete and permanent, be inherently “queer?” Indeed, the Foundation notes on its official website that the permanent memorial and museum will become “a sanctuary of love, hope, and healing that remembers the 49 lives taken in a senseless act of violence…” However, there is very little semblance of Pulse becoming a designated space to learn about LGBTQ+ culture other than commemorating the individual, mostly LGBTQ+ Black, Brown, and Latinx victims of the tragedy.

After three 2-hour visits, and a deep dive into the onePULSE Foundation’s official website, my dissection of the Pulse Interim Memorial illuminates the ways communities are grappling with the Pulse tragedy and the process of memorialization.2 Moreover, seeing what is and what is not communicated across an expansive wall presented as “Orlando’s contributions to Pulse” can be insightful to the future of how Pulse will be preserved and remembered in the projected $45 million planned museum and memorial.

Rainbows, Disney, and America: 528 Images Dissected

The dominant narratives across the wall were both affective (love, etc) and patriotic narratives. The visuals of might, strength, and local/national unity could be seen in images of civilians pledging to the flag, American flags embroidered to include rainbow colors, and the many ways that “Orlando Strong”—the most repeated phrase along the ribbon wall—was incorporated in items, letters, events, and clothing.

The recovery from Pulse included the City of Orlando and the police force that rescued survivors during the tragedy. These entities are visually reinforced along the wall which includes a newly-wrapped police car stating “Orlando UNITED.” The interim memorial also provides prominent space to corporations and organizations that exhibited their support and allegiance to the Pulse recovery. For example, Disney was a repeated thematic element across the wall–often times being used to accentuate the term “Orlando Strong” (drawing Mickey's ears in the “O” of Orlando) or the rainbow lighting of Disney's own Magic Kingdom Park.

The least represented narratives were about sexual identity, cultural identity, religion, and politics. 90% of the victims in the Pulse tragedy were of Latinx backgrounds — half were Puerto Ricans, three were Mexican citizens, and four were Dominican.3 The only area where their heritage identities were acknowledged is the secondary wall, which sits in front of the primary photography wall, where individualized posters honor each victim. This secondary wall is crucial as it centers exactly who defined the community, who loved coming to Pulse, and how their passing affected everyone around them.

In some instances where cultural or religious identity was represented, there was language to counteract its specificity in the service of patriotism. For example, one of the images reads:

The Arabic and Muslims communities highly condemn the barbarian terrorism attack which targeted innocents in Orlando City. We stand with you during this critical time. GOD BLESS YOU ALL.

Another example states:

I don’t care if you’re black, white, latin, asian, indian, muslim, straight, bisexual, gay, lesbian, religious, athiest, republican, democratic, rich or poor. If you are nice to me, I will be nice to you. SIMPLE AS THAT. – Orlando Strong.

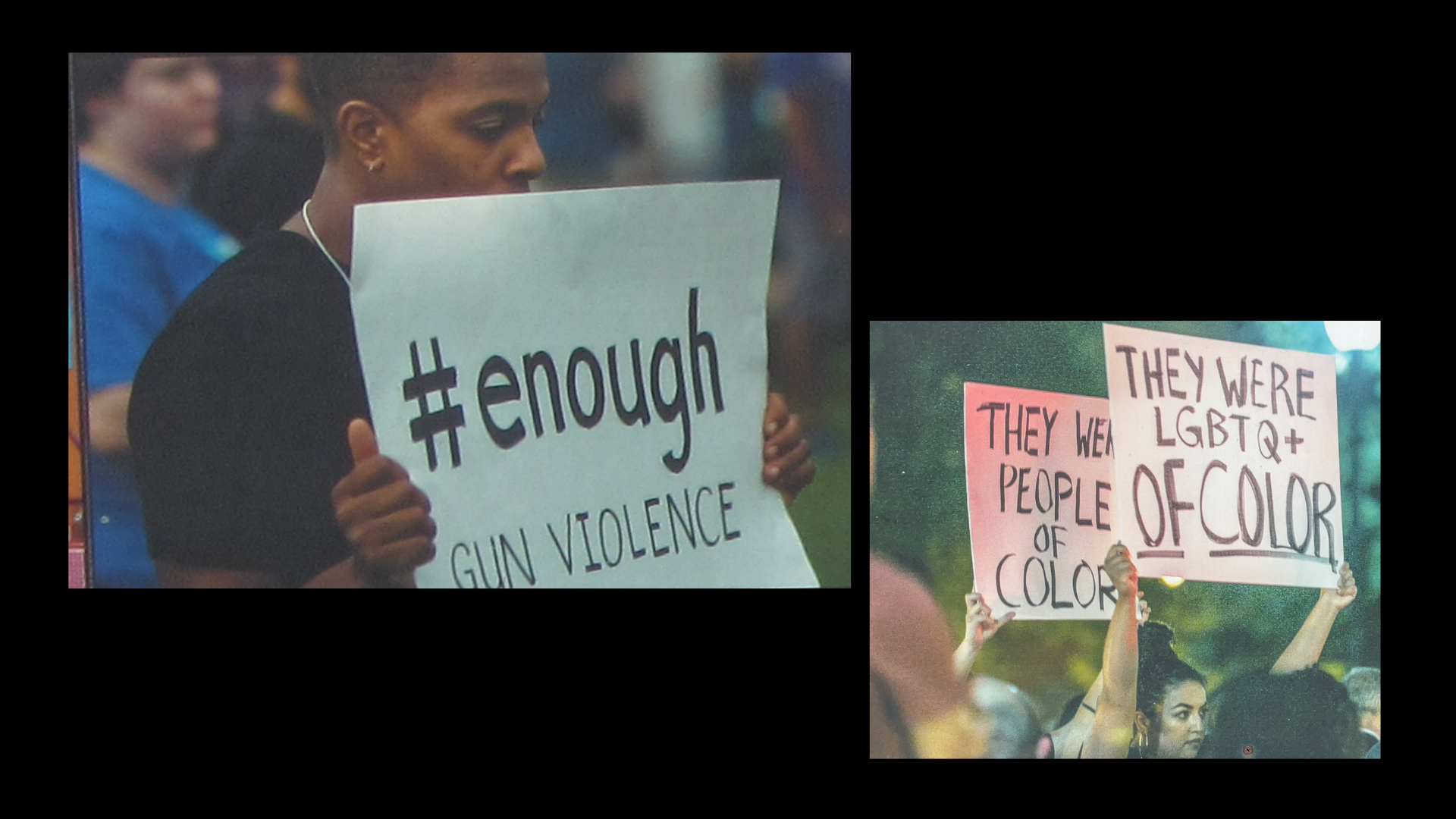

These two specific examples speak to a prevalent phenomenon in the wake of the Pulse tragedy: while the incident deeply impacted LGBTQ+ Black and Latinx people, there was a driving force to emphasize nationalism on multiple levels: that the shooting was an affront against the community, against Orlando, and against the United States. Only one image specifically references the victims of Pulse being LGBTQ+ people of color and another explicitly references an end to gun violence as a whole.

In the aftermath of Pulse, there was intense media focus on the shooter, Omar Mateen, and his connection to terrorist groups. Despite being born and raised by Afghan parents in the United States, framing Mateen as an anti-American terrorist fueled by hate overtook discussions on the wide availability and ease of purchasing guns in Florida. In E. Cram’s discussion of the Pulse tragedy aftermath, they write in reference to the recent memory of 9/11 that “context matters because narratives of catastrophe become powerful anchors of public feeling, their markings of place, bodies, and power as formative and heavy as their erasures.”[ref] Cram, E. (2016). Pulse: The matter of movement. QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking, 3(3), 147. https://doi.org/10.14321/qed.3.3.0147[/ref] In other words, community members and the media-at-large had an immediate tendency to stir fear around foreign terrorism as a motive for shootings. Regardless, what is lost in a more homogenized narrative that emphasizes terrorism and patriotism is an explicit lesson on the elements that lead to mass shooting tragedies, and especially how homophobic and transphobic sentiments justify targeted violence.

Reflections on Pulse, Power, and Legitimacy

The OnePULSE Foundation states its role is to: “create and support a Memorial that opens hearts, a museum that opens minds, educational programs that open eyes, and legacy scholarships that open doors.” The formalization of its role brought along recognition and support from powerful organizations and corporations. Indeed, by including images of the Apple logo to Macy’s employees and Disney logos on the ribbon wall, the Foundation is able to visually represent its legitimacy and institutional power. Likewise, in 2021, President Biden designated the Pulse Memorial as a National Memorial, which helped to further legitimize the Foundation’s work and encourage more vague calls to action, such as #outlovehate and assuring “incidents of hate never happen again.” And by recognizing the police and first responders, the memory of the Pulse tragedy has come to focus on the very moment of the shooting, as well as its immediate after-effects. Such subjects of memorialization are at odds with what’s urgently at stake: how are these victims publicly remembered? How do communities bereft in grief and shock commemorate what’s occurred? What stories will be told? And what is the message we leave behind?

Each year, especially in the month of June, I remember the shock and overwhelming grief I felt learning about the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida. Being Queer, Latinx, and Floridian, I read the names of the lives lost and see my own family and my own friends in the list of 49 victims. Pulse is still the deadliest recorded mass shooting of LGBTQ+ people in modern American history but today, it can be seen as a dot on the lengthy list of mass shootings in the United States (246 mass shootings have occurred from January-June 2022 alone). However, the renderings for the permanent Pulse Museum and Memorial at the interim site lack references to explicit political narratives about gun control or outright language discussing LGBTQ+ culture.

In my own reflection of this discourse and the ribbon wall, I wish for a continual push from organizations and community members to think of how Pulse is not just a static space that focuses on patriotism and #outlovinghate, but one for people to grapple with the factors that led to the shooter’s actions and what it means to support LGBTQ+ individuals that undergo harassment from institutions, and powerholders such as police departments. In my perspective, “queer memorials” are sites of reflection dedicated to gender and sexual minorities not acknowledged in larger historical narratives or tragedies.4 On top of that, queer memorialization can exist in different ways: The AIDS Memorial Quilt in Washington D.C. is an example where public commemoration does not require a concrete structure.

There can also be a reckoning to rethink how we memorialize recent mass shootings–especially as families of victims and survivors still undergo immense trauma. Perhaps it means congregating with survivors and providing open, natural spaces that offer reflection, activism, and resources. As Florida’s Governor cuts funding for mental health support that served Pulse survivors, there’s much more that we can do to lean into community remembrance work that can also benefit those directly affected by mass shootings.

* DeArmas, N., Miller, J. R., Givoglu, W., Moran, D. T., & Vie, S. (2018). Understanding participatory culture through hashtag activism after the Orlando Pulse tragedy. Discourses of (De)Legitimization, 126–150. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351263887-7.

Journal of Homosexuality, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2021.191391