When I was a sophomore in high school, I stumbled on a Ms. Magazine publication of Alice Walker’s essay In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens. The essay, which has come to transform my life and work, addressed the nature of Black women’s creativity in the American South. In it, Walker argues that though institutional, physical, and societal barriers have limited Black women’s freedoms to pursue artistic work formally, our essential creative spirit has not been destroyed. Rather, we have manifested our vivid, brilliant, and deeply powerful creativity in avenues outside of the traditional art world. Out of the necessity of telling our stories, Black women have developed inventive, subversive ways of making and thinking about art.

There are countless examples: the quilt hanging in the Smithsonian made by an “anonymous Southern Black woman” who, in the words of Alice Walker, “left her mark in the only materials she could afford, and in the only medium her position in society allowed her to use,” or Augusta Savage, who created the Harlem Art Centers to provide accessible arts education and content to her community, recognizing art as a powerful tool for transformation of the self and the larger society. One of the most striking cases Walker describes in the essay is of her own mother, who despite working long hours in the fields and at home, expressed her creative voice by tending painstakingly to her garden. The work of these women “mothers” our own—their resilience in articulating their creative visions leaves behind a legacy of “respect for the possibilities—and the will to grasp them,” inspiring and informing generations of creativity.1

A is for Assata from Abecedarium of Black Girl Magic, 2019. Embroidery on Dishcloths. Melissa Blount. (Photo courtesy of author)

Since first reading the essay, the question of how to honor and monumentalize these women, mothers whose artistic legacies guide the way for our own, has stayed with me. Part of me wants glistening bronze monuments to all the unsung heroines of our art history. But another part asks what there is to be gained, and what is lost in integrating our heroines to the visual and formal language of a traditional monument. Though they hold immense cultural capital, these monuments also maintain a distance from the lives of those who they ought to reflect. Monuments reify power structures as much as individuals, and in their traditional forms they “retain something of the demagogic,” leaving little room for what is personal.2 As monuments enshrine stories as historical artifacts in glass cases and bronze casts near centers of power, where is the work of keeping those stories alive for the disempowered?

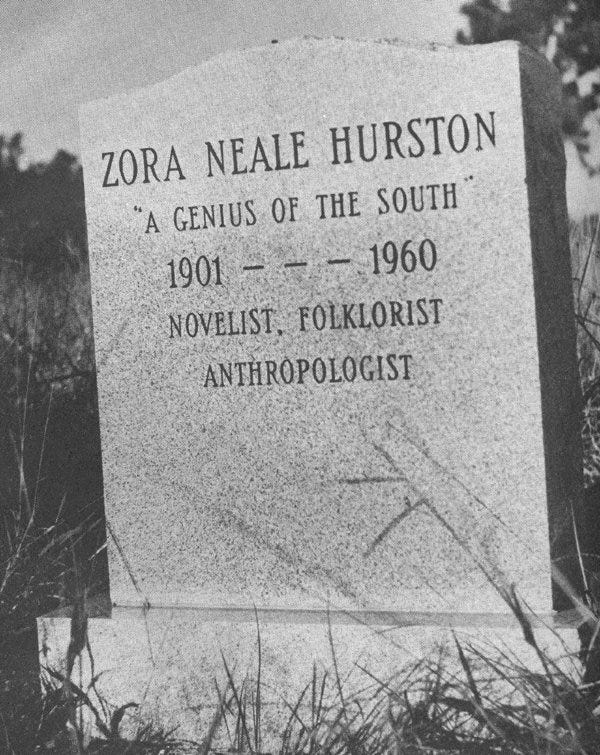

What would monuments to these women look like if they were personal, communally accessible, and tangible? Like Betye Saar’s altars, in which viewers don’t just passively admire, but contribute something of their own to the objects. Or the Organization of Black American Culture’s Wall of Respect, the mural of the names and faces of influential Black figures painted on a wall at 43rd and Langley in Chicago’s “Black Belt,” designed by community members and local artists. Or Thomas Hirschhorn’s Gramsci Monument, honoring the Italian philosopher’s maxim, “Every person is an intellectual,” with a summer-long offering of workshops and resources in the Forest Houses housing project in the Bronx.3 Or the headstone that Alice Walker commissioned for Zora Neale Hurston’s grave in 1973, after discovering that the “genius of the South” died in “poverty and obscurity.” Like all monuments, the location of the gravestone was as much a part of its story as its material—a consistent reminder not just of Hurston’s greatness, but of how that greatness had been misused and ignored.

Zora Neale Hurston’s gravestone, commissioned by Alice Walker. (Photo via University of Florida's George A. Smathers Libraries)

As Walker describes in her essay, Finding Zora, she felt an obligation to ensure that Hurston was monumentalized because, “We are a people. A people do not throw their geniuses away. And if they are thrown away, it is our duty as artists and as witnesses for the future to collect them again for the sake of our children, and, if necessary, bone by bone.” It is this meticulous process of collecting our geniuses “bone by bone—” an act of labor certainly, but also of overwhelming tenderness—that appeared inseparable from the essence of curatorial work. Curating, from the Latin root cura, meaning care, is necessarily related to digging out the rubble of our pasts, and finding within it that which we cannot afford to forget.

Walker’s act of care pushed me to look into developing a curatorial practice that would honor my creative mothers, and invite others to do the same. This curatorial framework would be informed by theories of womanism, which centers love for black women, values unification among diversity, seeks out the voices of the most marginalized, and is grounded in spirituality and ancestry.4 This womanist curatorial practice would honor the creative work that is ignored and misused—work which (like so much of women’s work) is made invisible. Through Walker’s writings and interactions with workshop participants, it became clear to me that as Black women’s external creative limitations multiplied, so did their ability to look beyond these limitations to redefine creative expression. At a workshop in October 2018, I asked audience members to share details of women in their artistic lineages whose creative legacies they’d like to honor, and I received stories about the women who crafted crowns out of hair, like Chicago artist Shani Crowe; the mothers who taught us to mend and weave; the grandmother-poets who inspired lifetimes of creativity. The diversity of these practices (some of which I myself had yet to face as deeply creative work) meant that womanist curation had to be willing to constantly work to deconstruct boundaries that define what is creative or valuable.

Womanist monuments to our creative mothers are visible in the fact that when Black women create today, we are telling our own stories, but we are also giving voice to the unsung stories of our mothers and grandmothers. Or, as Walker writes of Phillis Wheatley’s mother, “Perhaps she was herself a poet—though only her daughter’s name is signed to the poems that we know.” Thus, our continued creative production is a living monument to the work of those who came before us—one which we can pass down and make real; one which is infinitely reproducible; one which lives in memory, and touch, and movement.

Inspired by this framework of commemorating our mothers without trapping them in history, I developed the In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens series, a calendar of public programs building living monuments to the intergenerational and nontraditional creative legacies of Black women. In collaboration with Chicagoland artists who use their own practices to honor Black women’s stories, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens offered workshops that used active creative work to bring these stories to life.

Nicole Alcade-Hester working on a fabric square at the Black Lives Matter Witness Quilting Circle, March 2, 2019. (Photo courtesy of author)

The first workshop in this series took place in February 2019, when an intergenerational group of women gathered in a lunchroom at Chicago’s Village Leadership Academy for a community quilting circle led by Evanston artist Melissa Blount. Blount is creator of the Black Lives Matter Witness Quilt Project, using quilting to keep alive the names of Black women who were killed by institutional and interpersonal violence. In the workshop, participants learned about the artistic legacy of the Gee’s Bend Quilters, a group of Black women who have been creating striking abstract quilts in Gee’s Bend, Alabama since the early 1800s. They are women whose artistic practices have been passed down through generations, whose art originally served partly a practical function—quilts to divide rooms and keep their children warm—whose creative work was inseparable from the work of mothering (which, in making something out of nothing, is its own act of creativity). The group, including mothers from Ways We Make, a collective of mothers of color who meet to discuss and share resources around creative work and mothering, was able to discuss the parallels between the work of the Gee’s Bend women and their own creative practices, as they worked in the margins of life, using leftovers of material and time. They then collaborated on squares for a quilt that would be given to an incarcerated survivor of domestic violence. The quilt served two purposes: as a monument honoring her and her story, but also as a physical care object to cover her with love.

Participants at the Through the Lens workshop discussing the legacy of Black photojournalists in Chicago, March 29, 2019. (Photo courtesy of author)

As I reflected on what it meant to monumentalize our mothers’ legacies, I saw the need to reckon with the archive as a monument to particular ways of seeing, surveying, and categorizing Black womanhood. Like all monuments, the archive is constructed, yet made to appear as part of the landscape under the guise of objectivity. These public material, photographic, and textual histories, constructed by particular (White supremacist, patriarchal) power structures enforce their ontologies of Black womanhood, which displace intimate histories, and render everyday lives invisible. Two workshops in the series sought to disrupt this process by inviting participants to intentionally produce their own contributions to the archive from a position of agency.

In the Past, Present, Future workshop, participants were led in discussion by Renata Cherlise, a multidisciplinary artist whose work explores themes of identity and family, and brings archives to life in Black communities. The conversation covered Black women’s historical and contemporary positions within the archive, and then looked forward, creating digital archives of their lives through photographs and audio descriptions of objects and photos with significance to them.

Through the Lens was facilitated by photojournalist Tonika Johnson, whose work uplifts counter-hegemonic narratives of Black community. This workshop discussed how visual media (from the daguerreotype, to newspaper headlines, to Instagram snapshots) shapes narratives of Black women, and how we can create and curate our own visual narratives. The workshop concluded with a portraiture workshop, allowing participants to shape their own representations of Black womanhood.

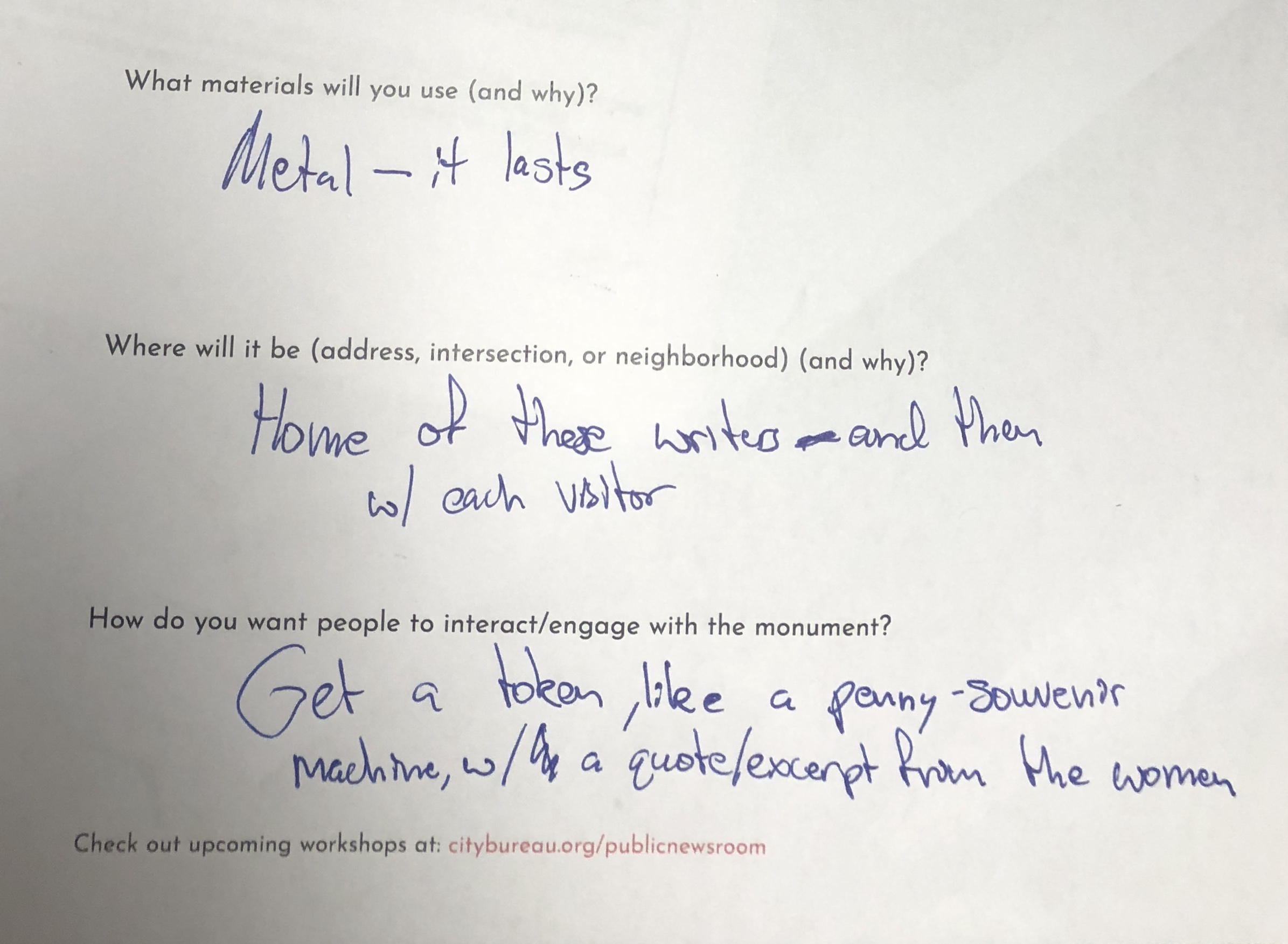

Plans for a monument to honor Octavia Butler and Leanita McClain, designed by participants in the In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens Public Newsroom, April 11, 2019. (Photo courtesy of artist)

The In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens series culminated in an exhibit of the art created in the workshop and by the teaching artist. Across mediums of quilting, painting, video, photography, and embroidery, the exhibit celebrated the myriad ways in which Black women’s artistic histories continue to be re-imagined. To celebrate the opening of the exhibit, a workshop was held in the gallery space co-facilitated by myself and Essence McDowell, whose book Lifting as They Climbed (co-authored with Mariame Kaba) tells the largely untold stories of Black women on Chicago’s South Side who transformed history in the city and beyond. After McDowell presented on several of the women’s stories, participants were invited to design a monument to a woman who was discussed in the book or who has been influential in their own artistic lineage. One of the blueprints that came out of the workshop was for a coin press that would imprint the writing of Octavia Butler, Leanita McClain (a pioneering Chicago journalist), and other great Black women authors. The monument would be both stationary (the press would be located permanently at the homes of these authors) and portable (the coins could be carried), questioning the limits of size on a monument, and asking how we can carry monuments and memories with us.

Grandma’s Kitchen 1, Archival Inkjet prints, Tonika Johnson. (Photo courtesy of artist)

In grounding my work as I curated this series, I continually asked myself why we needed to monumentalize and honor these women’s stories. The answer to this question was expressed strikingly during a panel conversation I moderated with the teaching artists. The question asked how the artists’ work was in conversation with “mothers” in their creative lineage. In response, Essence McDowell brought up that when she is experiencing frustration and anxiety over the state of our world, she is able to look back at the women in her book, and be confident in the knowledge that they already “came up with the blueprints” for our liberation. In Alice Walker’s essay, she writes that if Black women were to lose the knowledge of our artistic lineages, we would have “perished in the wilderness.” We must find ways to keep our mothers’ stories alive because they are our roadmap. So let’s rejoice, for we have not perished in the wilderness; we have the blueprint; we know the way forward.

Listen to full audio panel from In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens below.

On April 11, 2019, Tonika Johnson, Melissa Blount, and Essence McDowell gathered to discuss how their work within diverse artistic practices honor Black women's histories, explore connections between creative work and resistance to oppression, and redefine Black women's relationships to the archive. This discussion was moderated by Kanyinsola Anifowoshe to celebrate the opening of the In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens exhibit. This audio was recorded by City Bureau.

Listen to "Public Newsroom 103: In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens" on Spreaker.