Over the last 40 years, Nicaragua has been a country of no lasting resonance, trapped in a cycle of impermanence and urban deconstruction where innumerable monuments, buildings, and entire neighborhoods have been demolished.1 This political fashion has been imposed by each new government in attempts to erase the memory of their predecessor. The current regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo, who have ruled the country under an iconoclastic political dynamic since their reelection in 2007, has increased the deconstruction frenzy of landmarks across the country with an accelerated rhythm in the capital, Managua. Subsequently, their administration has commissioned a mass production of political imagery with no patrimonial value in lieu of the demolished monuments. The imposition of these new artifacts has been a key component in the political indoctrination program that has exacerbated police brutality, inequality, poverty, racism, and the suppression of education. Nicaragua remains a dictatorship where the lack of free speech and manipulation of urban spaces have intensified the need to reminisce history without any political bias. Therefore, the regime’s attempt to eradicate urban memory in order to insert its own political doctrine has created a collective resistance to oblivion.

Deconstruction Frenzy

During times of political turmoil, the cityscape can be experienced as parallel historic events, a living force defining its present based on its past and hopes for the future. In this dynamic, monuments function as symbols of history, resilience, and human achievements. Therein lies their importance in the built environment, as vestiges of time that can impact the development of society.2 While in many countries monuments are taken down, intervened, and recontextualized in the quest to redefine the politics of memory and oppression, in Nicaragua, these urban elements are destroyed and reconstructed in a reversed process of history by design.3

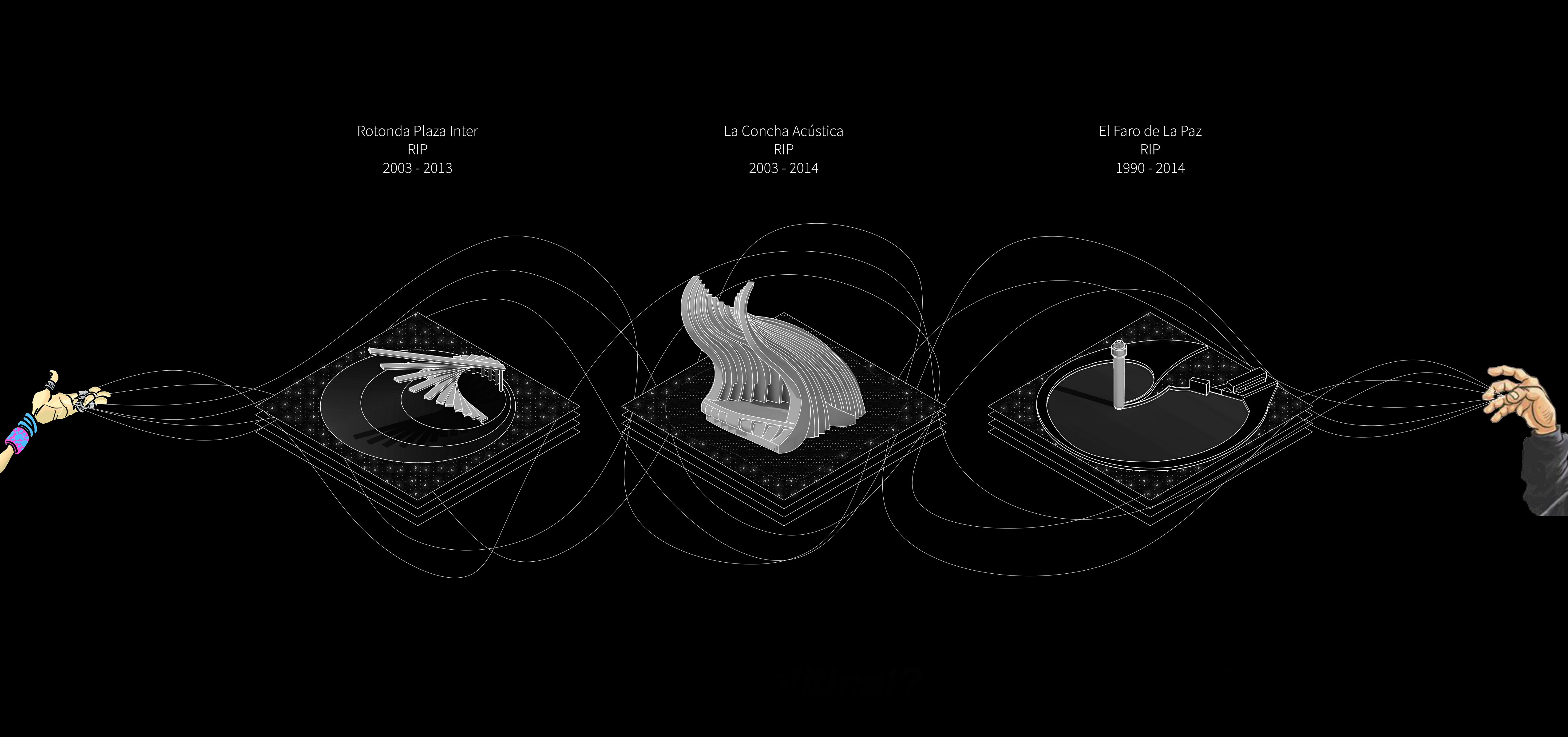

Among the demolished monuments in Managua, we find “La Concha Acústica” (The Acoustic Shell), “El faro de la Paz” (The Beacon of Peace) and “La Rotonda Plaza Inter” (The Plaza Inter Roundabout), along with murals, fountains, squares, and parks with relevant meaning to specific moments of Nicaraguan history. The volatility of the cityscape affects the capacity of communities to connect with the new urban imagery due to their lack of permanence and social agency. Consequently, the cleansing of landmarks by the current regime only emphasizes the loss of spaces where collective memories had been created. In this regard, the essence of the destroyed monuments prevails over their successors as a counter-memory that refuses to disappear. Additionally, technology amplifies our collective memory, so communities are able to track the constant changes in their cities to a point where demolished landmarks can embrace immateriality, and become ghost monuments.

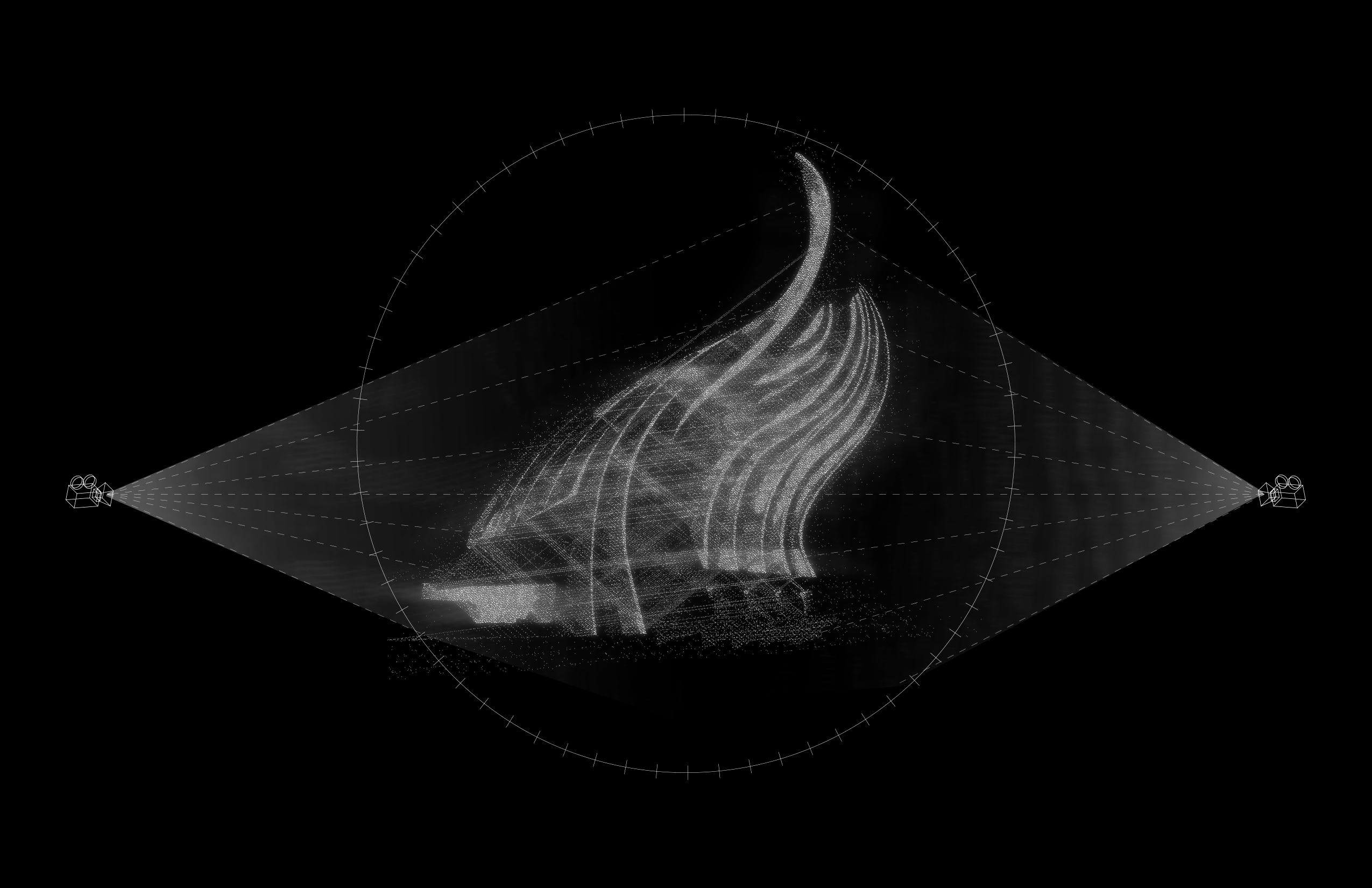

The murder of “La Concha Acústica” is one of the few well-documented case studies of destructive actions towards urban memory in Nicaragua. It was an outdoor amphitheater in Managua, located at the shores of Lake Xolotlán, between “Plaza Juan Pablo II” and the National Theater “Ruben Dario”. This monument was commissioned under the administration of Mayor Herty Lewites, who became the closest contender against Ortega for the presidency until his sudden death before the elections in 2006. The main purpose of its construction was to create an urban space for public events relating to art, culture, and music, as a way to promote community engagement. The architect for this project was Glen Small, who inspired its design in the silhouettes of the tropic. With the view of Momotombo Volcano in the background, the curvy monument resembled a flame emerging from the crater, moving along with Xolotlán breeze. By using traces of digital memory, it is possible to map the deconstruction process of this monument where patterns used in its demolition and other landmarks can be identified.

How to Kill a Monument in Seven Days

There are many ways to kill a monument. Often, the detachment between communities and their monuments is intentionally planned so that time can obscure their image. Likewise, environmental factors and other forms of neglect can quicken the decay of monuments, giving governments cause to demolish them. However, because regimes cannot always let time be their murder weapon, other actions are taken to accelerate the process of erasure for monuments that are slower to natural decay.

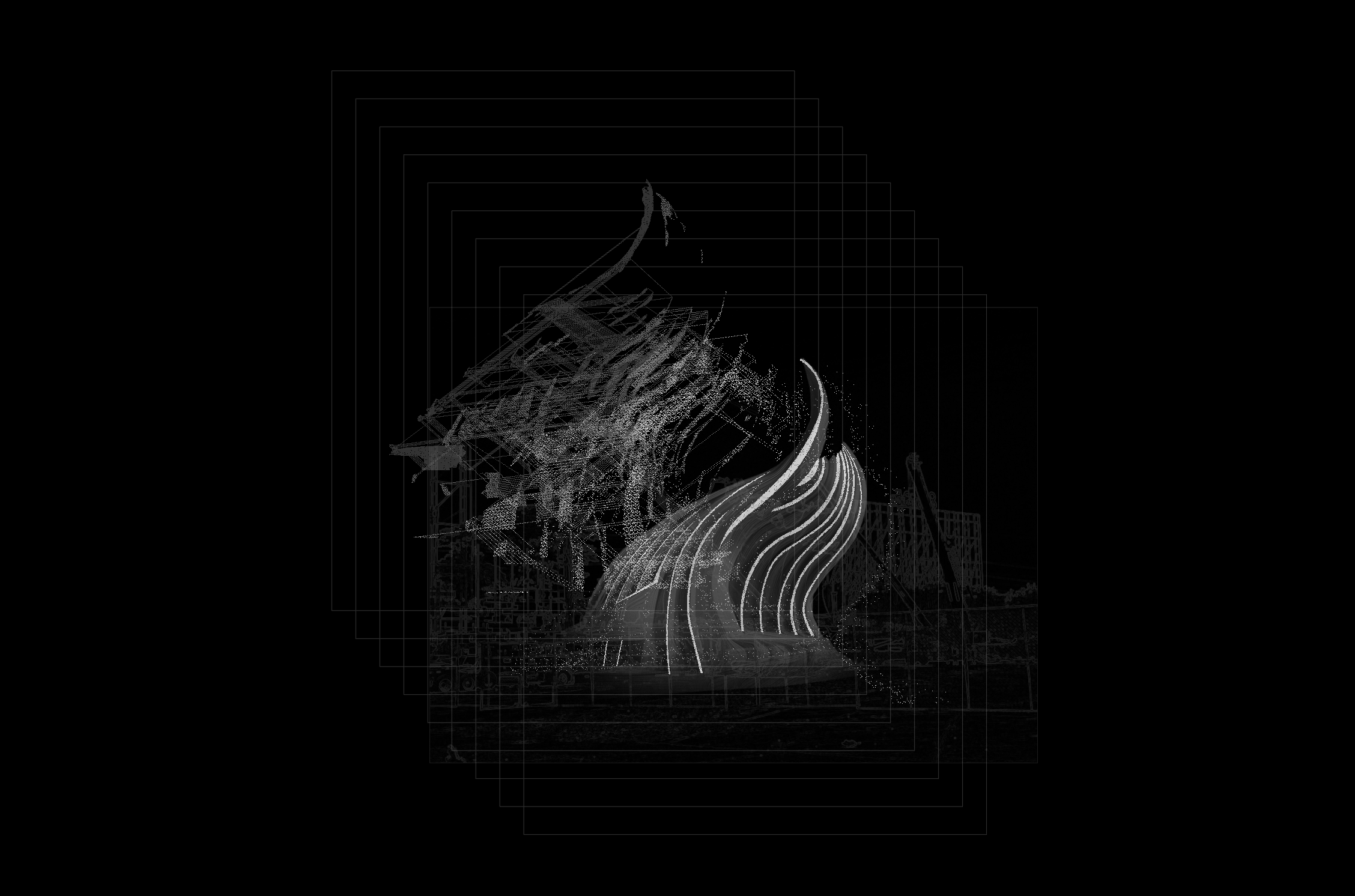

After the presidential reelection of Ortega in 2006, there was a rapid appropriation of the legacy built by the previous administration. “La Concha Acústica” became the selected space for Ortega’s presidential speeches and the celebration of events of the Sandinista party. The hijacking of the programmatic use of the amphitheater soon escalated; Leading to the start of the deconstruction process of this monument with a vandalism by the addition of political iconography. Several artifacts and propaganda were placed, attached, and even inserted into the monument, causing numerous superficial damages and notorious cracks on its concrete skin. Over time, “La Concha Acústica” was entangled in several layers of political propaganda in an attempt to appropriate its urban memory.

As the vandalism process only revealed the intentions of the regime, the obliteration of the urban landmark was the last resource to undo its memory. The deconstruction was carried out at high speed with no apparent explanation in May 2014. It was not until the process started that journalists asked Julio Maltez, an engineer employed by the Managua mayor’s office, who alleged that the structure was a matter of public danger since it could collapse at any moment, especially during a seismic event. The rest of the mayoral office’s specialists affirmed that there were irreparable fissures due to the constant seismic activity in the country that would only worsen with the rainy season corroding its inner metal structure. However, there were no official studies conducted to demonstrate the instability of the monument. Regardless of the unsustainable rationale and unlawful actions that were taken to approve its demolition, there was a clear manipulation by government authorities of the historic memory of earthquakes destruction in the country. In fact, Sergio Obregón, the structural engineer of the monument, affirmed that the constant seismic activity in Nicaragua could not have caused significant damage to the amphitheater and the cracks on its concrete surface could have been repaired.

During the first days of demolition, heavy machinery and a wrecking ball were brought to the site in an attempt to destroy the monument by smashing it; but its steel inner skeleton wouldn’t give in so easy. The allegedly unstable structure took seven days to collapse, resisting the government’s heavy machinery as the lie behind the monument’s structural instability was uncovered by its resilience.[ref[/ref]

Becoming a Ghost

The language of memory is able to carry on as its words are erased. Andre Aciman develops an interesting connection between memory and space, alluding to “ghosts spots” as those spaces charged with someone’s energy even after their physical absence as if their essence had been captured in a loop that keeps playing as their loved ones visit those spaces after their death.4 Aciman grasps the idea of memories printed on walls, furniture, and even instances when light enables a phantasmagorical reminiscence in certain spaces. Ghosts are usually imagined as entities trapped in a limbo between time and space. But what happens when it’s the space itself that becomes the ghost? Inversely, then, spaces become an entity trapped in our memory while creating parallel realities.

The ghost monument is not only one that lingers in the space where it no longer exists, but also extends into the possibility of reimagining the political iconographic monuments built at the rapid pace of the current regime’s urban memory monopoly. Intrinsically, ghost monuments are an antagonistic force against the rendering of the city as a unilateral space for denied accountability towards authoritarian ruling. Nicaraguan monuments have historically empowered the right to act. Subsequently, as if trapped in a cycle, during the socio-political reckoning of 2018 against the electoral reforms and violation of human rights by the government of Daniel Ortega, the political icons he created to replace historic monuments became the targets for graffiti and civic disobedience during protests. However, as we have come to see in our history, the mere destruction of political monuments will not help prevent a future dictatorship.5 Instead, it creates a void in memory. I thus argue that it is necessary to go beyond this amnestic pain and find a starting point to reconcile with our past without forgetting its aftermath.

After the demolition of “La Concha Acústica”, the regime commissioned to build from its remaining foundations a new musical fountain that only lasted for a few months. This new monument was demolished in August 2014 for a new major touristic urban masterplan at the shores of Lake Xolotlán The original site of the amphitheater became an arid plaza slowly populated with political artifacts. The physical absence of “La Concha Acústica” was a clear reminder of the regime’s crimes. Over time, the use of digital mediums allowed for a safe arena for protesting towards Ortega’s administration; immortalizing the memory of wrongfully demolished monuments and creating a parallel feeling of looking at the new monuments, but really seeing the past ones; as if their presence only serves to host the essence of their ghosts.

Monuments can be preserved through digital devices that transplant their essence from one medium to another. In this way, their story informs beyond their lifetime to also enlighten us about their deconstruction and the monuments created to replace them. The ghost monuments offer an intangible approach to understanding urban memory and recontextualization through design. In this regard, it opens the threshold for imagining the future of the current political monuments once the regime ends. Architecture has shown persistently how buildings can be repurposed and take on new typologies. On that premise, the regime’s creations could be recontextualized or repurposed. Then, instead of continuing a cycle of destruction, communities can design the decay of the political artifacts, reverting the scale of power by confronting hurtful memories with gestures of hope.

The chance to remember the past and yearn for the future is what maintains the endurance of communities who are living under oppressive systems. The digital memory of ghost monuments has created a safe medium for memory holding, as a silent reminder hid in plain sight for those who resist to forget.