Adjacent to an unmarked trail in Washington, D.C.’s Rock Creek Park, several hundred feet southeast of an active maintenance yard, a wooded area evades both stringent upkeep and easy characterization. For at least forty years, hundreds of slabs, chunks, and discs of sandstone, granite, and marble—all formerly parts of the United States Capitol—have covered at least 15,000 square feet of an otherwise nondescript site. Amassed in haphazard stacks and wall-like configurations, the stones bear evidence of stagnation and decay. Thickets of overgrown brush obscured several piles on a recent February day. Bright green sheaths of mildew and moss covered countless surfaces. The only visible sign nearby read, “Area Closed.”

In the 1950s, planned renovations of the Capitol building precipitated a large-scale demolition of its East Front portico. Elements of the facade dating mostly to the early nineteenth century were dismantled and dispersed across D.C. over several years. A set of Corinthian columns, for instance, eventually achieved recognition as a landmark housed by the National Arboretum. But the stones moldering in Rock Creek Park have inherited no such acknowledgement. Their presence strikes a much more ambivalent tone. Though they lie on National Park Service land, no instructive signposts guide viewers’ encounters. Their positioning resembles abandoned architectural ruins, yet a structure never stood in their place. They attest neither to permanence nor to the exhaustive ownership of a singular powerful agent. They remain devoid of an authorized narrative and profess no cohesive set of beliefs. In a city of over-administered municipal and public spaces, this is a rare site whose meanings have not been predetermined. Visitors have deemed the stones an unofficial monument, but what makes it a monument? And what would make it official?

Abstractions of the “Official”

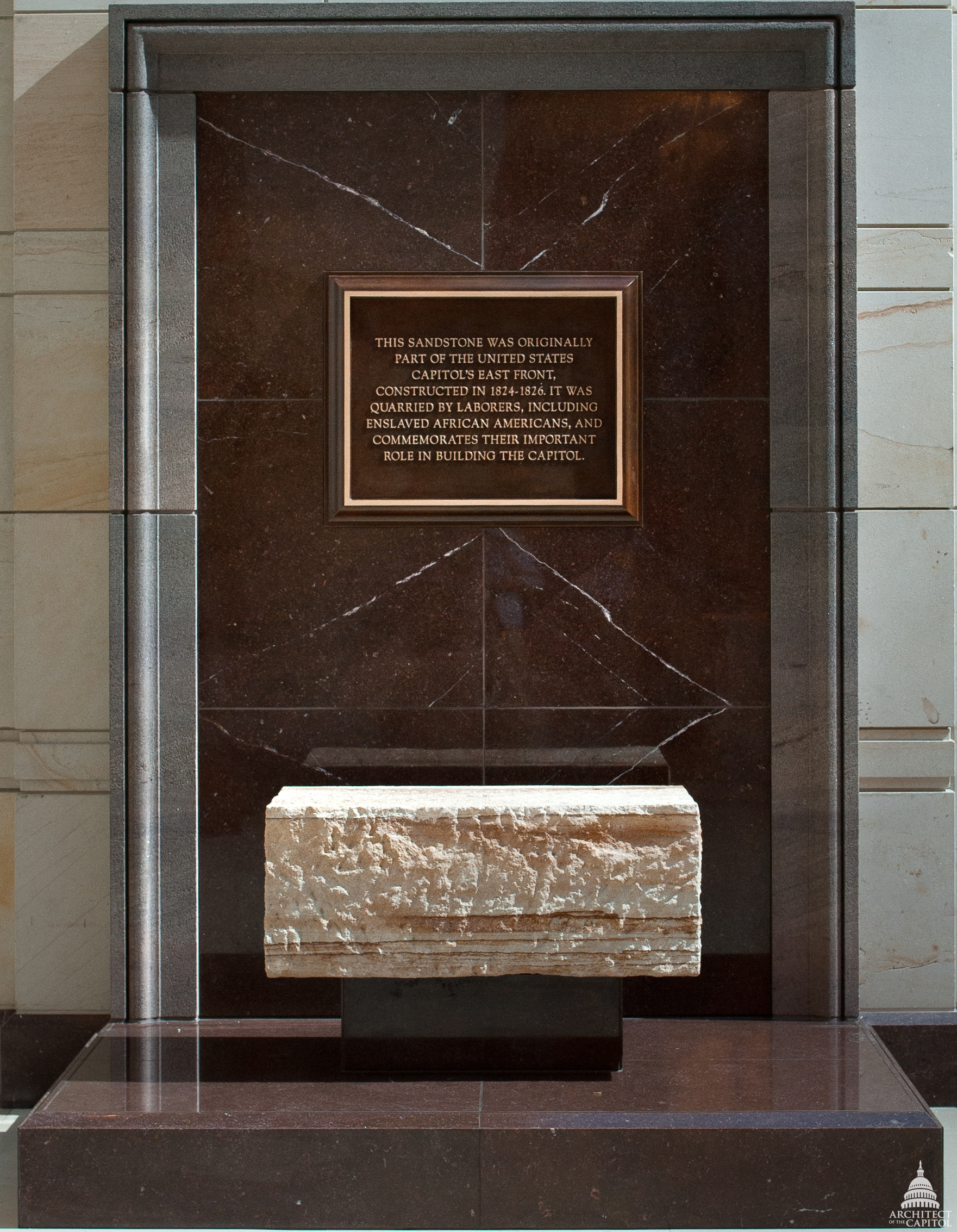

About eight miles southeast of Rock Creek Park, another block of sandstone from the Capitol’s East Portico has received markedly different treatment. By all accounts, its features are much more aligned with those of “official” monuments. It sits atop a marble pedestal against the northern wall of Emancipation Hall in the Capitol Visitor Center (CVC). Its spotless surfaces are the color of eggshells, save for the taupe-hued strata cutting horizontally across multiple sides. A bronze plaque identifies the sandstone as a marker commemorating labor performed by enslaved people in the construction of the Capitol, which began in 1793. The CVC’s accompanying brochure describes this appropriation of enslaved labor as a matter of necessity and expediency. It cites Washington D.C.’s rural eighteenth-century environs as a “fledgling city” in which “skilled labor was hard to find or attract.” Relying heavily on enslaved labor at this time, the brochure states, ensured the Capitol building’s completion prior to Congress’s relocation to Washington from Philadelphia in 1800.

This text abstracts and sublimates the foundational roles that transatlantic economies of enslavement played not just in the literal construction of the Capitol, but in the sociopolitical imaginaries that willed and enabled its existence. William Thornton’s original eighteenth-century designs for the Capitol building performed a similar sublimation. Architectural historian Peter Minosh notes how Thornton’s plans for a dual-elevation neoclassical structure aimed to mediate urban and pastoral ideologies: it would provide an intimate approach from its urban-facing east side and an anchor for the National Mall’s sprawling, picturesque square to the west. This vision’s realization relied on a leveraging of American plantation economies (which had displaced agricultural production to the South), yet the Capitol landscape’s constructed elegance would ultimately erase any trace of the structural violence that supported its production.1 An insidious whiteness inherent to the Capitol’s design manifests in this process of obfuscation. Per Minosh, Thornton’s plans were predicated on a biopolitical apparatus that figured enslaved peoples as commoditized subjects, yet the Capitol’s architectural performance of democratic ideals and Enlightenment-era “disinterested reason” invisibly subsumed this apparatus’s workings.2 The Capitol and its grounds’ initial configuration thus enacted an abstraction of the violent, racialized regime that birthed it.

The brochure text accompanying the CVC’s commemorative marker to enslaved labor demonstrates how these abstractions can persist through contemporary gestures of bureaucratic liberalism. The marker’s presence in Emancipation Hall possesses undeniable historical significance and a palpably striking visuality. However, its contextualizing language aims to account for enslaved people’s “contributions'' without condemning (much less naming) the abject violence through which those contributions were conscripted. This bestowal of an “official” narrative to the marker can promote a sanitized mythos of restitution, especially in the absence of materially reparative enactments of policy.

Manifold forms of racism propagate within such spaces of historical and epistemological abstraction. Prison abolitionist and geography scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore has described the lethal pitfalls of these abstracting operations as “displacement[s] of difference” into hierarchical, organizational structures that delineate relations among sovereign political bodies.3 Constructions of racialized subjects and nation states alike emerge from these displacements. For justice to be embodied, Gilmore argues, it must be considered as resistive to the ways in which racism pervades spatially, geographically, and through processes of place-making. It must combat the abstractive modes through which whiteness obtains power and maintains alterity—discursively, physically, materially—in the spaces it creates and the places it occupies.

The discarded Capitol stones at Rock Creek Park may not actively advance forms of embodied justice, but their conspicuous lack of context creates valuable space for interventional thinking. Marked only by material encroachments of geological time, the stones throw into stark relief the abstracting discourse that frames their staged counterpart at Emancipation Hall. They harbor the ambiguity of untold histories, implicitly questioning how state-sanctioned monuments’ professed histories might reinforce machinations of colonialist thought. They remind us that regardless of any intended functions or imputed narratives, every monument implicitly opens spaces for doubt and contestation.

Abstraction’s Inheritances

Racialized practices of abstraction have proliferated across American public discourse and social relations for centuries. Their consequences, however, crystallize in much less abstract phenomena: all too familiar acts of erasure, claims to power, and other forms of structural and corporeal violence in service of hegemonic whiteness. In recent months, these consequences have compounded in assertions of proprietorship over public spaces and state-operated structures, most notably the U.S. Capitol.

One such assertion came in the form of the December 2020 executive order promoting classical architecture as the “preferred and default” style for public federal structures in Washington, D.C.4 The order cited precedents set by George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, who ensured that the original White House and Capitol’s columns and triangular pediments embodied classical antecedents of democracy and self-determination. The order contended that in recognizing these structures’ historical connections, contemporary citizens should be reminded “not only of their rights but also their responsibilities in maintaining and perpetuating [the] institutions” of their national republic. Jefferson, an enslaver himself, personally chose Thornton as the Capitol building’s designer. Indeed, the two men subscribed to the same colonialist frameworks that deemed non-white people bereft of a privileged subjectivity that could attend to universal reason. What, then, lies at the core of the institutions to be “maintained and protected,” if not the self-preserving interests of whiteness ensconced in neoclassicist facades of sandstone, granite, and marble?

Assessing the events surrounding the January 6th Capitol siege, historian Lyra Monteiro recalled American statesmen’s Enlightenment efforts to map classical signifiers of power onto early federal architecture. She drew a direct historical throughline from the logic of these undertakings to that of the insurrectionists, who aimed to “rescue” an abiding model of white western empire by plundering that model’s most salient monument. The throughline Monteiro identified was that of “white heritage,” an assumed inheritance to social, political, and economic power ascribed to Greco-Roman “societies” that has steadfastly endured in paradigms of racial difference and state-sanctioned structural inequity. The insurgents understood the impending transfer of presidential power as a threat to that heritage. In turn, for several excruciating hours on January 6th, the Capitol ceased to be a tool of the political and cultural abstraction of white violence. This abstraction fell away and it became the domain of a white mob seeking to forcefully reclaim a monument to which they felt unduly entitled.

Now, in the siege’s long aftermath, an eight-foot tall chain link fence festooned with barbed wire encircles the Capitol and its legislative campus. It additionally surrounds the Supreme Court, the Library of Congress, the U.S. Botanical Gardens, several roads and pedestrian throughways, as well as thousands of square feet of public green space. This barricade and the National Guard troops dotting its perimeter severely undermine some of Thornton’s primary spatial concerns. No longer are the urban and pastoral juxtaposed in a harmonious, sprawling tableau crowned by an unimpeded view of the Capitol building. Instead, “the people’s” temple to democracy remains utterly inaccessible to the people it purports to serve. An air of surveillant, militarized defensiveness has discomfitingly settled across its environs.

If the fence stands as a visual consequence of the Capitol’s breached sanctity, let it also stand as an undeniable testament to the neoclassical “geography of domination” that has mythologized that sanctity.5 Let the fence’s protective impenetrability evoke the calamitous dangers that arise from abstracting centuries of violent whiteness. Let the fence’s imposing presence visually undermine this abstraction and, like the stones at Rock Creek Park, invite reinscriptions of spatially embodied knowledge and agency. Let the Capitol’s three-mile-long enclosure remind us that every monument’s story—whether “official” or otherwise—is necessarily a permeable, unfinished one.

The author would like to thank Mashinka Hakopian, Katherine Hand, Judy Salveson, and Michael Salveson for their invaluable input and support of this text.