“If, like James Joyce wrote, ‘history is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake,’ then history is something that is constantly under construction…”

In the city of Bristol, a former slave port at the height of British empire, protestors tore down the statue of the notorious enslaver, Edward Colston. Rolling him over to the harbor where he was symbolically drowned, Colston subsequently sank to the bottom of the same ocean that claimed the lives of those forcefully displaced and enslaved on their transatlantic journey to the Americas.

As the weight of the past bears down on the minds of the living, communities across the globe connect contemporary injustices to a longer genealogy of racism and oppression folded into the fabric of empire. Monuments are symbols in a system, and toppling, defacing, and destroying monuments should not be viewed as solely disorderly acts. Instead, reckoning with monuments signals a re-ordering of our concrete and imagined worlds, a symbolic overthrowing of current political regimes. In what follows, I discuss how monuments suffer from what the Haitian historian and anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot has called, “the burden of the concrete,” which arguably never leaves us but is always under construction. I then move on to exploring how Trouillot’s ideas help us understand when and why monuments must be destroyed through examples from Mexico, Paraguay, and the Republic of Ireland.

Monuments as Concrete Burdens

In his classic book, Silencing the Past: Power and Production of History, Trouillot crafts a theoretical framework for understanding the myriad ways that power and history are inextricably linked. Trouillot is deeply concerned with how “power enters the story” and emphasizes the role of silences or absences in the production of history. For Trouillot, the production of history is always uneven, stained by struggles for equality in a world premised on colonial, capitalist structures that depend precisely on the reinforcement of inequalities. There is an inescapable tension to the making of history because every act of “historical production”, like assembling an archive or erecting a monument, means choosing one narrative and potentially silencing many others. So, too, there is a distinctly material quality to history for Trouillot. Not only are there the facts of the matter for historians to consider, but the matter of facts. Monuments are an example of this. They are the matter of history, proof that something or someone came before us. Trouillot’s notion of what he calls “the burden of the concrete” emphasizes the role of matter – or materiality – in producing and validating particular historical narratives. In some ways, “the burden of the concrete” points to how material evidence makes history real within a Western purview. As Trouillot eloquently writes, “…history begins with bodies and artifacts: living brains, fossils, texts, buildings.”1

Yet these material receptacles of history are rarely, if ever, neutral. Symbolic and emotionally-charged, monuments – whether they appear as statues, murals, or architecture – testify to purported historical truths and speak to which histories matter and to whom they belong. The palpable silences hidden inside monuments haunt us. To gaze upon a monument or take it into our hands forces a confrontation with the material reality of history and the reminder of its uneven production. Monuments render the ghosts of the past inescapable; monuments can be literal concrete burdens, stony facades reminding us of violence and oppression. “The bigger the material mass, the more easily it entraps us…”2 Suddenly, the “weight of the past” takes on an emotional and visceral meaning. How do we exorcize the ghosts and suture old wounds? Dismantling, destroying, and removing monuments is one way to confront monuments that have become concrete burdens.

Dismantling: Views from Latin America

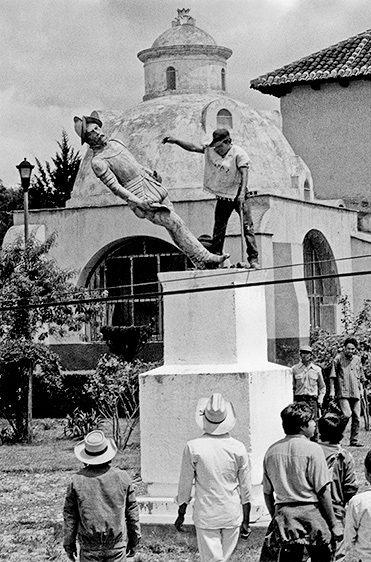

Deconstructing a monument’s form is a powerful social and political statement. To quote Dan Hicks, “...their physical removal is part of dismantling systems of oppression.” Recent examples of dismantling - from decapitation to dismemberment - can be found in Chile and Paraguay, the latter being an instance where a steel monument memorializing Paraguay’s former dictator, Alfredo Stroessner, was sundered apart, disassembled, and melded between two blocks of concrete.

In San Cristóbal de las Casas, the capital city of Mexico’s Chiapas state, indigenous Mayan leaders tore down and deconstructed the monument of Spanish conquistador, Diego de Mazariegos y Porres, on October 12, 1992. This date commemorated the 500th year anniversary of Spain’s conquest of the Americas. The Emiliano Zapata Campesino Organization had planned its removal, and also orchestrated the resistance march that culminated in dismantling the statue. Alongside Andrés de la Tovilla, De Mazariegos colonized Chiapas and “founded” San Cristóbal de las Casas in 1528. Whereas the state-sanctioned narratives of Mexico celebrate a mestizo culture, Indigenous scholars like Yásnaya Elena Aguilar Gil argue that the ideology behind this – known as mestizaje – conceals colonial structures and further reinforces racist policies against Indigenous Mexicans by assimilating their culture and claiming it as everyone’s while also silencing their voices. Dismantling the ‘material memory’ of conquistadors is one way to counter history and grapple with this particular concrete burden. The mere presence of these conquistador statues is a symbolic colonization of public space. Toppling the statue before an audience signals empowerment and is an active disavowal of a history stained by genocidal acts and the continued marginalization of Indigenous people. Here, people took control of the narrative in order to negate colonialism. The gaping social, physical, and psychic wounds inflicted by de Mazariegos – and the conquest in general – are sutured through resistance and the literal fragmentation of his violent legacy.

Destruction and Displacement: Rubble in the Republic of Ireland

A second mode of killing monuments is through a totalizing destruction. Individuals and collectives might obliterate monuments using dynamite or bombs so that all that remains is rubble or dust (and possibly the shade of whatever that memory may be). Even after they’re destroyed, however, these material receptacles of memory persist in our archives. We might even say that they occasionally return to haunt us.

At least that’s what has happened in the Republic of Ireland, a former British colony, which achieved independence in 1922. While Ireland was still under British rule, authorities unveiled a statue of Field Marshal Hugh Gough, a high-ranking colonial commander, in Dublin’s Phoenix Park. One of Ireland’s most contested public statues, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) recognized the equestrian monument as a symbol of British imperialism and made five attempts to dismantle or destroy it.

Why the persistence, one might ask? What’s most important to understand here is that Ireland is not a ‘recent’ colony. The British colonization of Ireland began in 1536 and crystallized in the early 17th century with the Ulster plantations. For nearly 400 years, segments of the Irish population organized multiple rebellions against the British settlers until they finally achieved independence. Yet despite independence, symbols of British rule continued to occupy public spaces and remind the Irish of a past with which many would rather cut ties. Destroying the Gough monument was imperative. It was beheaded in 1944 but governmental authorities both recovered the head and soldered it back on. In 1956 the IRA blew up the monument, but only succeeded in damaging the horse. Finally, IRA forces orchestrated an explosion in 1957 which at last blew the Gough monument off its pedestal and into pieces.

Although the story (and memory) might end here with the monument’s death, its rubble was rescued and brought to England where it was ‘painstakingly’ restored by Humphrey Wakefield. It is now leading a second life as a fixture of Chillingham Castle. When talks of repatriating the Gough monument to Ireland occurred in the 1980s, Ireland’s Department of Justice contended its repatriation was undesirable, even dangerous. One of Dublin’s ‘vanishing statues’ targeted by the IRA as they decolonized and severed ties or memories of British imperial rule, the Gough statue is one of many ghosts of colonialism that no one needs to see return.

Concluding Thoughts

As the Saint Lucian writer Derek Walcott reminds us in his poem, “The Sea is History,” our actions leave indelible marks on the land, sea, and each other’s bodies and minds. Yet history, “the sound” coming from furtive chambers “like a rumor without any echo,” is always a construct bending to the will of those in power.3 This instrumental quality of history is something Trouillot adeptly highlights through his “burden of the concrete” and his concept of “silencing.” If we think of silencing as an active and decisive act, then we can see how monuments are condensations or bundles of silences. They often represent a dominant narrative and hide other historical realities and experiences. In other words, their mere presence makes known a palpable absence.

Trouillot also remarks upon how monuments “embody the ambiguities of history. They give us the power to touch it, but not that to hold it firmly in our hands – hence the mystery of their battered walls.”4 Monuments make silences real just as they realize particular political agendas. Vibrant, tangible, and dynamic, monuments are concrete burdens to be reckoned with. The killing of monuments is another way to interrupt narratives of power: quite resolutely, their destruction is a forceful reassertion that we get to choose who and what matters. History is always under construction.