Flooding of pathways surrounding the Tidal Basin. Photo Credit: Sam Kittner. Photo provided by the author.

Washington, D.C.’s iconic Tidal Basin is sinking. Built in 1890, the Basin was meant to regulate flood waters and keep shipping lanes open along the Potomac. By allowing silt and sediment to flow in and out with the tides, the engineered waterscape negated the need for constant and often futile dredging. Starting in the mid-20th century, the Basin also became a renowned commemorative landscape, gradually encircled by the Thomas Jefferson (1943), George Mason (1990), Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1997), and Martin Luther King, Jr. (2011) memorials.1

The memorials are tucked into a canopy of beloved cherry blossom trees, which attract a million visitors that flood the Basin during their short-lived but much anticipated bloom. Millions more come to see the memorials over the course of a year. Meanwhile, the National Park Service, which manages the Tidal Basin as part of the National Mall and Memorial Parks, is facing a backlog of hundreds of millions of dollars in differed maintenance costs in the Basin alone.2 The pressures on the Tidal Basin are enormous, and so is the potential for a different future.

Embedded Pasts

In 1901, the Senate Park Commission, known colloquially as the McMillan Commission, was formed to create a cohesive vision to guide the development of the nation’s growing capital. In its report to the Senate the following year, the Commission left much development potential for future generations. In envisioning a possible pantheon on the site of today’s Jefferson Memorial, the authors wrote that the ultimate decision “may be left to the future: at least the site will be ready.” The foresight, however, was conditional: the Commission recommended that any new buildings or infrastructure must duly respect established styles and visual relationships. This primacy of an established order became paramount in the mid-20th century battle against rampant urban renewal.

Made into law in 1966 to protect against the unbridled razing of historic properties, the National Historic Preservation Act established the National Register of Historic Places. Administered by the National Park Service, the Register has grown to contain some one and a half million contributing properties. Often offering nominal protection unless a property receives government funds, listing in the Register establishes which aspects of the historic look need to survive to retain integrity, tied to a set period of significance. The recently expanded National Mall Historic District’s period of significance begins in 1791, after settlers drastically changed the surrounding landscape.

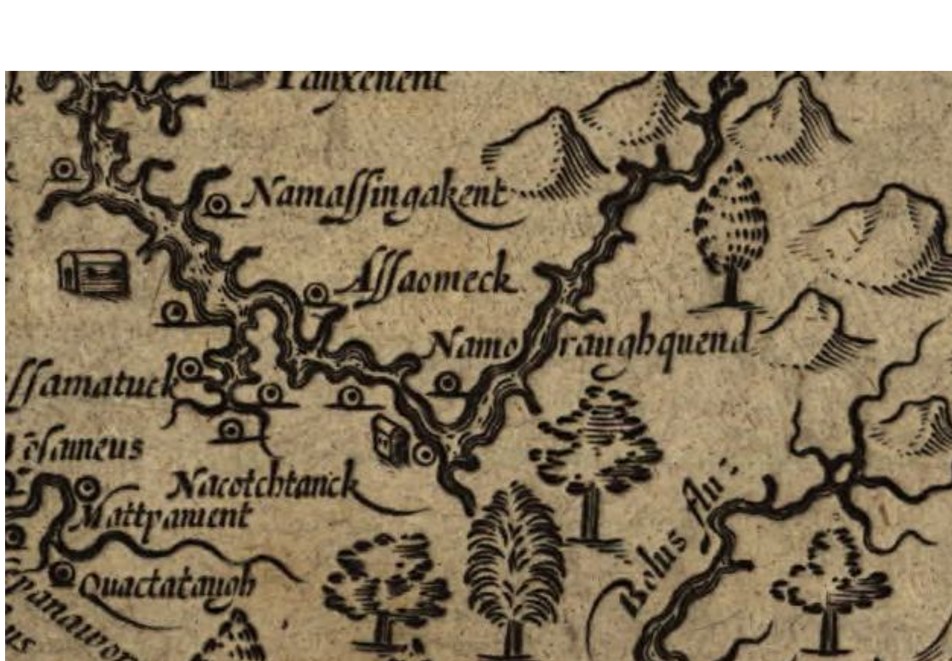

Detail of John Smith and William Hole’s 1624 map of Virginia showing the Anacostia River and nearby settlements near the site of the Tidal Basin. Image credit: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division. Image provided by the author.

Recent opinions in the press regarding the appropriateness of the Jefferson Memorial have brought up questions about the disparity between reverence and reality. What has come to the fore is an overdue stripping away of layers upon layers of settler-colonial aesthetics. The McMillan Commission’s continuation of Pierre L’Enfant’s axial configurations and forced sightlines are alien to the personal relationships between land, water, and cultures that have existed for thousands of years. When Indigenous communities were consulted on the redevelopment of False Creek Park in Vancouver, for example, plans for an overlook were removed in favor of an approach into the water, an act of defiance against the dominance of constructed views.

Flexibility of appropriateness, at least in style if not in subject, was established in the forward-thinking Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture, written in 1962 by Daniel Patrick Moynihan and issued during the Kennedy Administration. In them, Moynihan recommends that “the development of an official style must be avoided.” If Moynihan’s suggestion is extended to a broader conclusion, an official time should similarly be averted. With a deeper sense of time, the Potomac would be allowed to return more fully, and so to would its enduring cultural associations.

The Potomac and its tributaries were high roads of trade, ideas, and gossip shaped by enormous ecological pressures as well as everyday acts of cultural endurance. In The Old Ways, Robert McFarlane writes, “along the sea paths for thousands of years have travelled ships, boats, people, objects and language: letters, folk tales, sea songs, shanties, poems, rumors, slang, jokes, and visions.”3 As with other long stretches of shoreline, the river can be seen as a continuous territory, a geography that flips our land-based concept of boundaries on its head. From this vantage point, water is zone of encounter that unites rather than divides, a lively space of exchange both fraught and friendly.

Comparison between 1793 shoreline and 2019 projected flood zone. Image Credit: DLANDstudio. Image provided by the author.

The original impetus for the Tidal Basin was a mixture of major flooding and the clogging of mercantile passages, a result of ecological disruptions from agriculture, industry, and settlement that clear-cut forestland and removed absorbent wetlands. The disruptions boomeranged back onto the settlers: five strong floods occurred between 1856 and 1867 alone. Intensive dredging projects tried to keep shipping lanes open until the work was wiped away after a particularly strong flood in 1877. Soon after, a previous plan to create a winter harbor protected by infill was adjusted with sluicing basins and construction of the Tidal Basin began.

The story of the Tidal Basin’s significance does not begin when engineers filled in West Potomac Park, or with Pierre L’Enfant’s 1791 plan for the federal city. The Tidal Basin’s story is not just about the reclamation of land, the control of water, the planting of trees, or the placement of monuments: its history and its future are really about the inseparable interaction between people and the landscape. The Potomac was not a backdrop; it was and still is a lifeway, with its own gravitational pull.

Today, this construction—in essence an engineered replication of natural processes—is slowly being subsumed by the forces it was built to control. This ongoing process of decay, antithetical to preservation, offers an emergent, less rigid, and far more inclusive vision.

Emergent Futures

The only thing inevitable about the Tidal Basin is entropy: the slow mixture of natural and cultural forces into a steady state of ruin. Robert Smithson’s concept of “ruins in reverse” elucidates that a sense of timelessness occurs because of change rather than in spite of it. For Smithson, ruins are not failure but are instead a living work open to the unknowable. Viewed this way, ruins, defined elsewhere as “where nature and humankind work together to form a collaborative work,”4 are inevitabilities to be encouraged, and perhaps guided, rather than stalled at all costs.

The value of this perspective is in showing a flipside to the current standards of preservation practice. To retain integrity, preservation standards demand that any alterations or additions are guided by four specific treatments: preservation, rehabilitation, restoration, or reconstruction. The most flexible of the four is rehabilitation, which aims for minimal, compatible change to the historic fabric.5

Cultural exchange, however, does not depend solely on the material. By viewing the landscape through the lens of ruin, a different, as-yet unsanctioned treatment positions entropy as paramount. In this fertile ground, anonymous collaboration frees unknowable possibilities. Through this optic, change is inexorable and meaning trumps materiality.

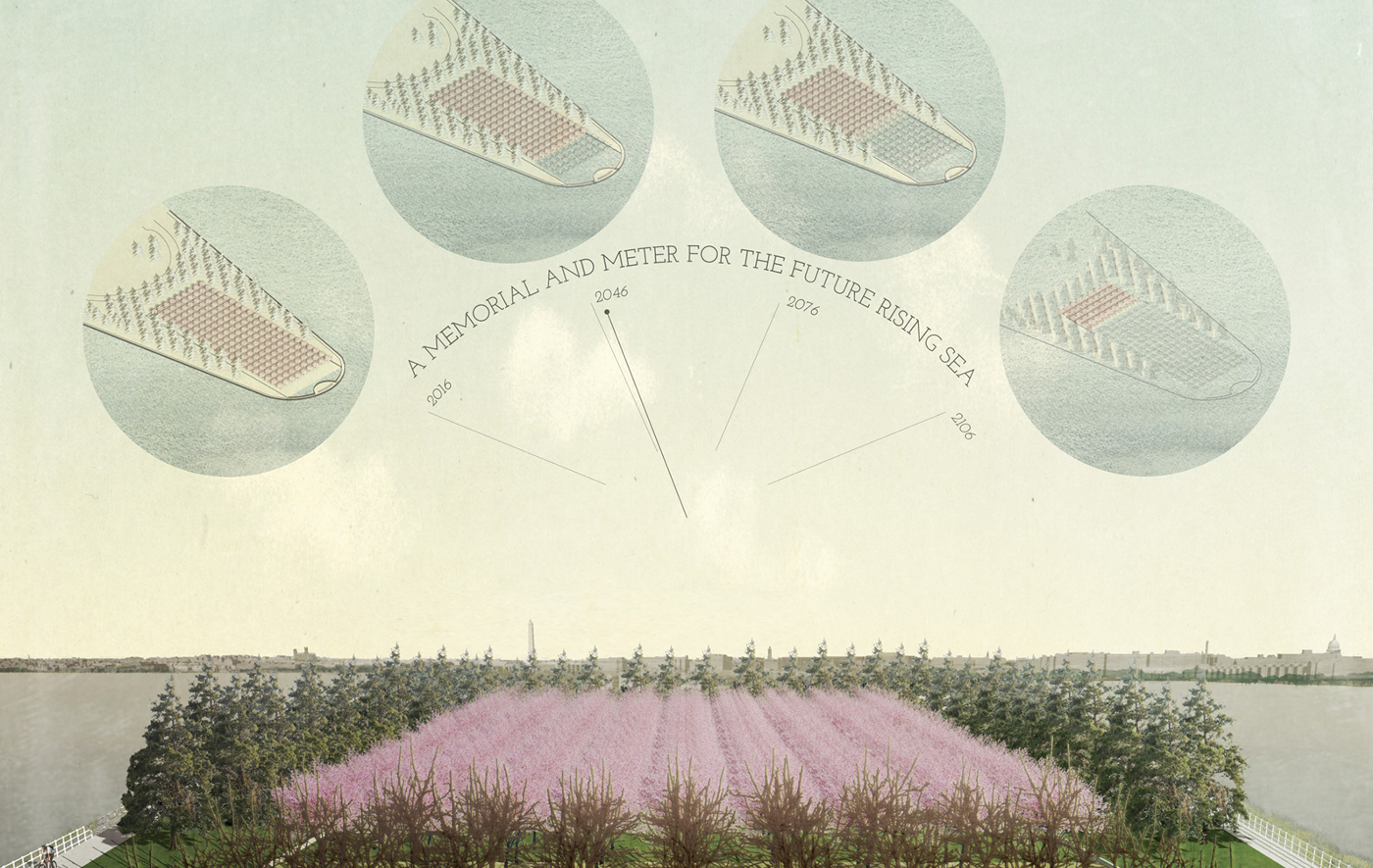

A focus on meaning and an openness to change can be seen in several recent proposals for the future of the Tidal Basin and nearby areas. Thinking specifically about function, the Memorials of the Future competition sought to explore the experience of commemoration, with many proposals embracing fragments over grand narratives and variation rather than stasis. Timed with the 2016 centennial of the National Park Service, the competition was the result of collaboration between the Park Service, the National Capital Planning Commission, and the Van Alen Institute. Lasting six months and open to designers, artists, and social scientists from across the country, the competition sought to challenge traditional, inflexible memorialization aesthetics that do not allow for change or multiplicity of perspective. Out of some 89 entries, four finalists were selected by a committee of professional jurors.

The finalists, in coordination with competition partners, produced visionary proposals that combined the past and future as one inseparable force. The Van Alen Institute’s key findings noted the possibility of temporary, ephemeral forms as well as added functions, especially the commemoration of universal experiences, such as climate change. The winner, Climate Chronograph by Azimuth Land Craft, which remains unbuilt, proposes rows of cherry trees at Hains Point that gradually die off row by row as sea levels rise. The emergent process leaves bare, weathered trunks to decay in place: the poignant reverse of “preservation in place.” Here, the ecotone – the transitional edge between communities – is central, and every visit reveals a new reality: new ideas are just as important as past notions, and age loses its significance. Alive within a kaleidoscopic, ever-changing cultural aesthetic, the commemorative landscape reveals itself as a thin place where new and old meet and see no difference in each other.

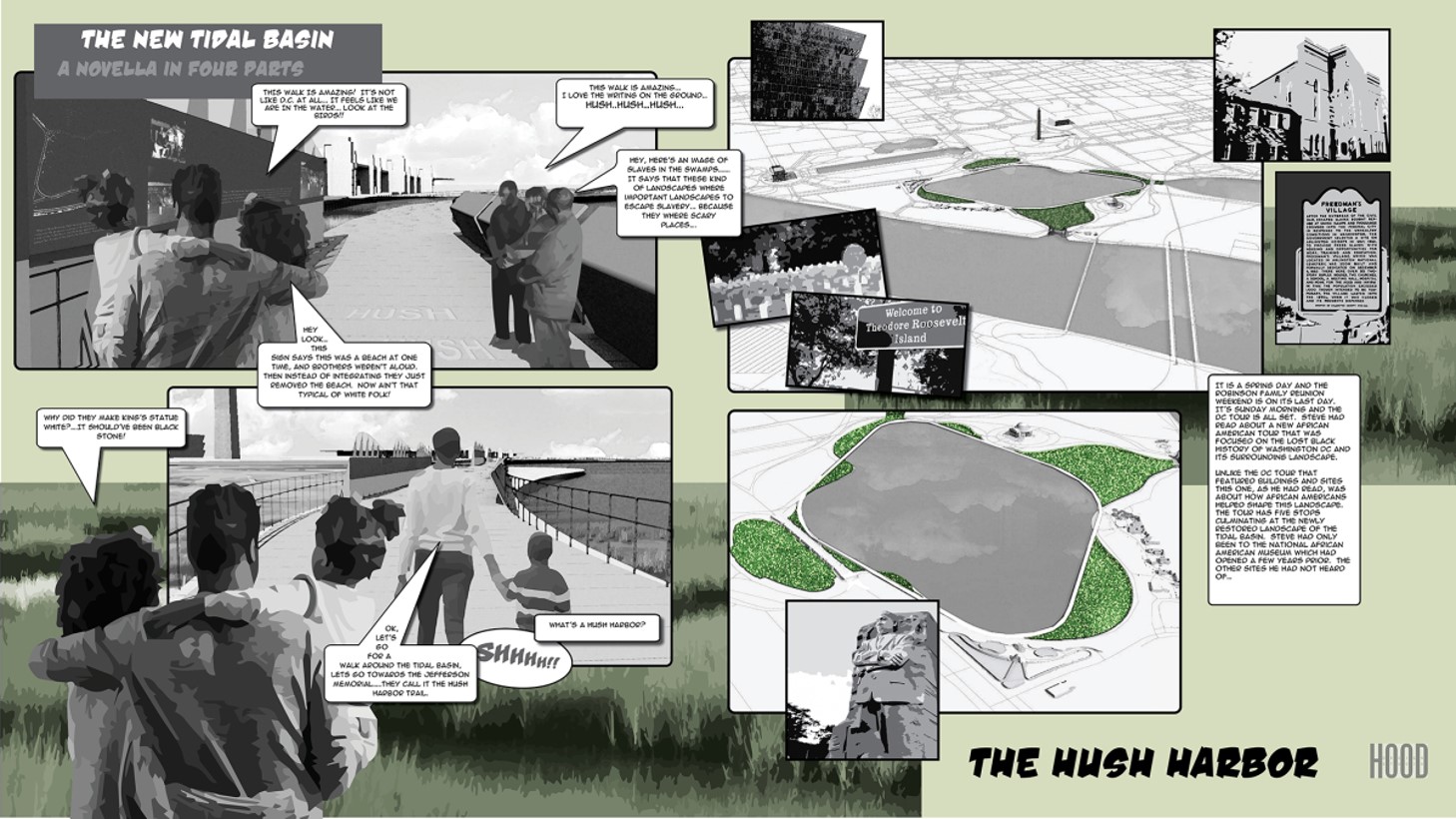

Hood Design Studio, Hush Harbor concept of the Tidal Basin Ideas Lab, 2020. Image credit: Hood Design Studio. Image provided by the author.

In 2020, the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the Trust for the National Mall launched the Tidal Basin Ideas Lab to draw attention to its needs and build support for a creative vision for its future. Originally proposed as an in-person exhibit at the National Building Museum, the virtual exhibit features proposals for the Basin’s future from five leading landscape architecture firms: DLANDstudio, Gustafson Guthrie Nichol (GGN), Hood Design Studio, James Corner Field Operations, and Reed Hilderbrand. Unlike a design competition that selects a single winner, the Ideas Lab is a cooperative visioning exercise. While each firm developed its own scenarios, an animating ideology emerged that harmonizes ecological and cultural forces. This ideology, unveiled slowly in a decades long process, softens edges, embraces flooding and tidal cycles, and abandons expectations of control. Origin stories give equal voice to the marginalized while memorials are allowed to accrete new forms and meanings.

Launched during the pandemic, the Ideas Lab incorporates public feedback driven through local and national media attention. Participants largely echoed designer intent, sharing a desire to introduce new ecological systems, especially wetlands and marshes, and better knit together the Basin with its surroundings through expanded circulation networks. Speaking to traditional monuments, one respondent noted, “if we honor the past by stone structures only, we miss the bigger picture.” By extending the commemorative landscape to include everyday lived experiences, from pre-settlement to the unknowable future, the Basin itself becomes a memorial to possibility. The result is a synthesis of potential, a bricolage of nature and culture, future and past. Seen in this way, the Tidal Basin is limitless: boundaries decay into each other, expectations collapse, entropy takes over.

What emerges is an understanding that the contemporary condition is temporary, and the only thing to confidently strive towards is the unknown. As recent proposals observed, the unknown is nothing to be afraid of. Untethered from sanctioned, authoritative definitions of style and time, the Tidal Basin models a speculative preservation treatment and, in the end, becomes whatever it wants to be.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Jeanne Dreskin and Caitlin Schnur for their invaluable thoughts and edits.