One major expectation of a monument is that it will last. This hope derives from its role as a reminder, as an object intended to outlive those who erected it in order to perpetuate a story they want heard. Durable materials such as granite, marble and bronze are generally preferred for this purpose. They are considered well-matched to resist the perilous weather and everyday hardship that comes from their traditional placement outdoors.

Fig1: Abraham Lincoln during his annual spring clean, April 1994. (Source The Atlantic)

Sometimes, however, monuments need a little maintenance. This maintaining is usually referred to as restoration or preservation. It involves the participation of specialists who are knowledgeable of material properties, chemical compositions, and various techniques. Yet, the language of science and preservation has a tendency to obscure what is also going on here. Restoration projects and monument maintenance are ultimately an expression of care and, critically, a form of validation.

Scholars of memory have tended to focus on the more conceptual or contrary aspects of this process. Most famously, Pierre Nora argued that sites of memory result from the decline of “living memory” and the failure of communities to keep the “real environments of memory” alive. In this sense, monuments emerge when the memory of what they represent is no longer present or intrinsic to our everyday lives.1

While maintaining monuments might similarly be regarded as an ‘everyday’ or ‘routine-like’ engagement, there is a distinctly different emphasis. Maintaining a monument makes an investment in the current memorial landscape. It involves the effort and labor of others whose success is premised on making invisible change.

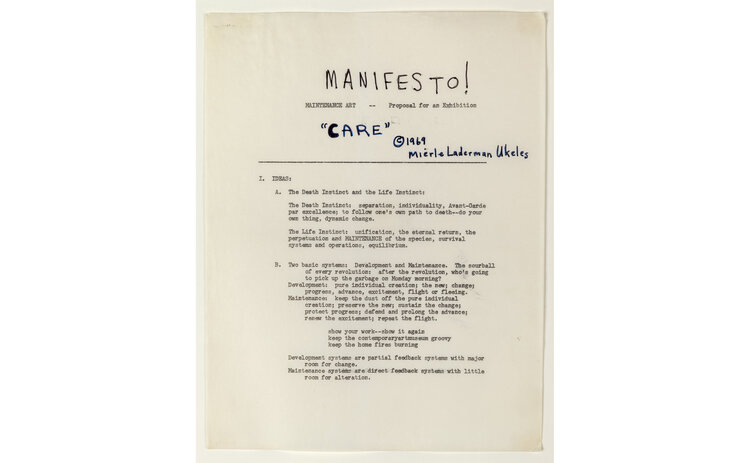

In 1969 the artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles wrote a manifesto calling on us to appreciate this kind of hidden labor. She performed repetitive and time-consuming tasks as well as celebrated the people typically assigned them. It is easier to create than maintain, she argues, and the activities involved the latter are just as worthy examples of art.

This valuing of process is important, but should not necessarily be construed without aim. The issue of what should be maintain and why raises important ethical questions. In this context, we might ask what are the costs of keeping the “real environments of monuments” alive.

Fieldwork

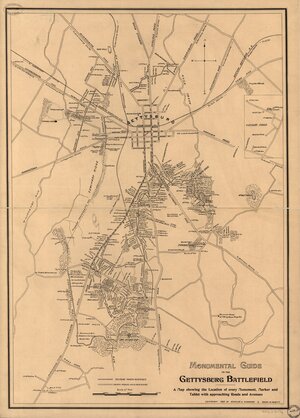

One place where this task is particularly epic is Gettysburg. Home to over 1300 statues and memorial markers, you would be hard put to find a place more monument-dense than this famous battlefield. During its early years, when there was just 350, the battle monuments were all under the care of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association, a Pennsylvanian corporation who owned the field and ensured a superintendent was ‘constantly in charge’ to oversee it.2

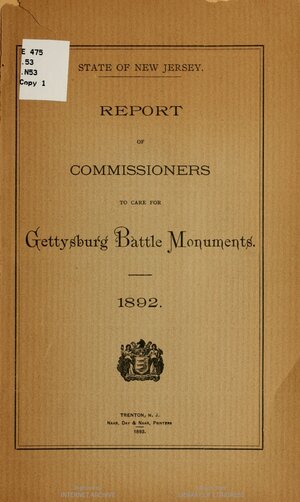

Individual states and sponsors also contributed to the upkeep of the monuments placed there. According to the 1892 ‘Report of Commissioners to care for Gettysburg Battle Monuments’, New Jersey legislators set aside $1000 annually for “the purpose of properly enclosing, improving and caring for the said monuments and grounds.”3 Commissioners from Vermont also appropriated a sum of $2500, “to be expended by the officers of the Gettysburg Battle-field Memorial Association” for the “rebuilding and repair of earthworks, and otherwise caring for and beautifying the Gettysburg battlefield grounds”.4

This work continues today. “One possible description for preservation projects wherever they may be seems to be ‘never-ending’ or perhaps ‘on-going’,” states Barbara J. Finfrock, vice chair of the Gettysburg Foundation.5 Care of the battlefield’s monuments is currently under the auspices of the National Park Service and Gettysburg Foundation, and low staffing levels are making recurring maintenance a challenge.6 The cleaning of monuments involves time, money and effort. At Gettysburg, the aim is to clean each of the 1328 monuments at least once every four years. For those made of lower quality bronze this frequency increases.7 These activities fall under the purview of the Maintenance Division of the Monument Preservation Branch at the Park, headed by Lucas Flickinger, who aspires to “touch up or maintain roughly a third of the collection each year”. His colleague, Michael Wright, has apparently “lost count of how many cannons he’s repaired.”8

Funding for maintenance projects generally derives from the Park’s partnership with the Gettysburg Battlefield Preservation Association and Adams County Bank.9 Formed in 1997, this initiative began life as ‘The Pennsylvania Gettysburg Monuments Project’ and identified 146 monuments and markers affiliated with Pennsylvanian regiments “in need of repair and routine cleaning and maintenance.” Now the Gettysburg Battlefield Monument Trust, the project provides “an endowment for future maintenance”, covering “all the non-equestrian Pennsylvanian monuments on the battlefield in perpetuity.”10

Although the Park sometimes relies on volunteers for some types of maintenance work, its ‘Park Watch’ programme for example, the continual upkeep of monuments means costs add up. In 2018, the budget listed $52,465,303 for deferred maintenance, meaning a sizable proportion of their funding is committed to this task.11

New Monuments / As good as new?

Given the number of monuments in its collection, Gettysburg might be seen as exceptional in terms of maintenance duties. As the site of the Civil War’s most bloodiest battle, however, the history and mythology associated with the place has inspired the necessary investment. It is considered a key turning point in the Civil War, a moment of great Confederate defeat from which the South failed fully to recover. Yet, while the Confederacy lost the war, it is often said to have won its memory. The continued existence of Confederate monuments at Gettysburg and in the South testify this, and the maintenance of them validating.

As a National Military Park and Museum, Gettysburg provides an educational and commemorative setting for the contextualization and care of these monuments. Those located on more public grounds and walkways, however, give rise to different interpretations and demands. Often protected by law, the maintenance of these monuments poses ethical issues over the use of public funds.

A special report by the Smithsonian and the Investigative Fund at the Nation Institute in 2018 found that American taxpayers contributed at least $40 million to the upkeep of Confederate monuments. In the past ten years alone, they reveal, “Virginia has spent $174,000 to maintain the Lee statue” that still looms over Richmond, and $500,000 to guard it when protest groups assembled there in 2017.12

As opposition to these monuments continue, their maintenance costs simultaneously rise. While solutions such as relocation, destruction or the creation of new monuments are by no means cheap, crucial value judgements are made to make them look ‘as good as new’.