Empty concrete slab where the tall bronze statue of the President of the Confederate States of America Jefferson Davis once stood, Memphis Park, Memphis, Tennessee. (Photo by author)

Memphis Park sits on the edge of its namesake city above the banks of the Mississippi River. A low stone wall encircles its western boundary, clinging to a hilltop, conjuring the remains of a fort or garrison. You can approach the park from a network of refurbished pathways and pop-up public spaces closer to the water’s edge, up a stone staircase also resembling a relic. At the plateau, the park covers an extended city block, and its eastern edge rejoins the core of downtown Memphis, a block from Court Square.

Its former name, Confederate Park, is now scrubbed from the physical surroundings. Good riddance to the landmark that stood to reinforce a generic, lingering sense of power and white racial rule, a designation just as pernicious as the valorization of particular traitorous slaveholding generals or soldiers.

But the park’s new name, Memphis, remains generic in a different sense. Operated by non-profit Memphis Greenspace, the name suggests inclusion for the city as a whole, a platform for representation despite the space’s contested legacy. Online, some traces of the old name still remain as if the park’s memory extended, like a four-star rating on TripAdvisor posted as recent as last summer.

Memphis Park is embedded within a larger riverside cliff designated for a massive, multi-million dollar campaign to revitalize the waterfront as part of the region’s civic commons. A 2016 report from Groundswell outlined the plans for renewal, envisioning “using connected, thriving public spaces to attract Memphians who may not ordinarily interact.” Last year, Memphis Greenspace hosted activities, like Hank Willis Thomas’ Truth Booth, yoga in the park, and the city’s first Dîner en Blanc. As Van Turner, Director and President of Greenspace, noted last year, “Let’s recreate the parks and put there what people want...The slate is clean.”

The day I visited Memphis Park I was joined by my friend and Monument Lab designer William Hodgson. We were in town to install an exhibition at Rhodes College on the other side of town, but our first day was spent in search of the city’s commemorative sites, past and present. That day, it happened to be Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday. He would have turned ninety-years-old. In a city that celebrates his legacy as much as it still mourns the trauma of his assassination more than fifty years ago, the entanglement of time and geography was on our mind as we ascended the stairs to the park.

We found in the middle of the park what we were looking for: an empty concrete slab, where a tall bronze statue of the President of the Confederate States of America Jefferson Davis once stood. The sculpture was installed in 1964 and removed by the city in 2017, after the strategic sale of the park to Memphis Greenspace, and importantly, following years of grassroots organizing especially the activist-led campaigns of Take ’em Down 901.

Removal of the Jefferson Davis statue in Memphis Park, Memphis, Tennessee. (Photo courtesy of Andrea Morales)

More than a year after a crane removed the statue, and months since the pedestal was disassembled, there were few signs of struggle that remained. The park had been rebranded. The old World War I cannons that used to surround the sculpture, had been removed, too. Only if you read the accounts, heard the testimonials of the takedown, and seen images of the struggle, could you discern what the empty cement signifies.

At the park, the most salient current reminder that something grandiose had been there before: a pair of lights remained, shining upward into the space that the statue had occupied, now an unintentional monument of sorts. The park lives as a simultaneous public space and public void.

Across town, on Union Avenue, the fate of the city’s other confederate statue looms. The statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest, Confederate General and Grand Wizard of the KKK, was removed the same evening as Davis’s. There, in the renamed Health Sciences Park (formerly named for Forrest), the empty pedestal still stands, encircled by a cyclone fence and punctuated with traffic cones, as its owner, Memphis Greenspace, is embroiled in lawsuits with Forrest’s descendants and the Sons of Confederate Veterans. The question as to whether Forrest’s and his wife’s remains were disinterred from a local cemetery and placed under the pedestal as a part of its construction remains unresolved and at the center of this ongoing challenge.

Greenspace faces a different dilemma in Memphis Park. There, the landscape is not in a state of arrest or shock, and no lawsuits hinder redevelopment. With its Confederate monument and other designations removed, the surface of the park offers hope for new chapters.

But even in Memphis Park, where placemaking pleasantries have replaced cannons, the question remains: Can the site of a former confederate monument and park become neutral ground?

In 2016, when Groundswell issued a report about the redevelopment of the Memphis waterfront, the Jefferson Davis Statue stood. This text box was placed in front of it to hinder its view. (Memphis Civic Commons Presentation via Reimagining the Civic Commons)

Modern day Memphis Park sits on the city’s “Fourth Bluff,” the area is part of the larger Chickasaw Bluffs, a geological formation that stretches along the Mississippi’s edge and historic overlook that also served as refuge from floods. In a sense, the bluffs are named in homage to one of the main indigenous nations of the region, the Chickasaw, the same nation coerced from their lands, whose removal paved the way for the founding of the city of Memphis in 1819.

In 1831, Alexis De Tocqueville, while writing Democracy in America, arrived in Memphis and witnessed the removal of Native peoples from several tribal nations several hundreds yards away from the modern-day park, noting, “in this manner do the Americans obtain, at a very low price, whole provinces, which the richest sovereigns of Europe could not purchase. These are great evils; and it must be added that they appear to me to be irremediable.”1

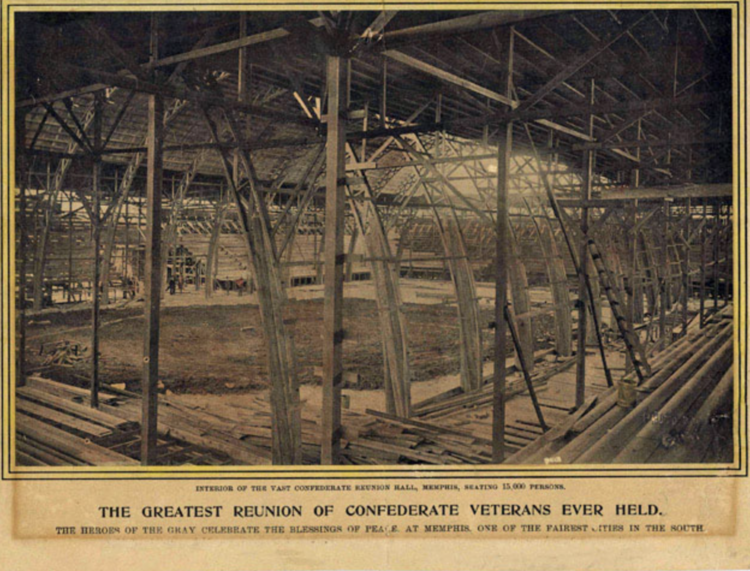

According to local histories, including a particularly textured account from Vance Lauderdale in Memphis Magazine, the park that resembles a fort was never a place of Civil War battle. Instead, its name comes from the national reunion of United Confederate Veterans held in the area in 1907, hosted within a temporary 18,000 seat wooden pavilion.

UCV Reunion Hall 1901. (Historic Memphis)

A year later, the area was dedicated as a park, with wooden signs proclaiming it a “Memorial for the Old South.” At the time, Memphis Chairman of the Park Commission, Robert Galloway, reportedly laid out the vision:

"My idea being to make this an old Confederate fort, [with] fallen-down stone parapets, guns partly concealed by vines, white jessamine, etc."

An invented landscape, for leisure and a pointed form of confederate commemoration, helped define public space as segregated, a military fantasy for Confederate apologists.

Civil War artillery was installed, but later scrapped for a different, later set of canons. Beyond this, there are plenty of oddities to the park worth digging into, not the least of which a bed of pansies colored and shaped as the Confederate battle flag were planted and removed. Again, according to Memphis Magazine, in 1962, when the park was under threat from development of a shopping mall, the question of who actually owned the park may have halted the construction plans, keeping the park intact. The questions around ownership did not matter for a park that invoked the Confederate memory as its source of legitimacy.

The installation of the Jefferson Davis statue in 1964 read like a grander gesture at exerting control over the park and its surrounding areas. According to John Branston in the Memphis Flyer, the statue was in the works for ten years, including an $18,000 fundraising campaign in which “the United Daughters of the Confederacy, later assisted by the Sons of Confederate Veterans, were the driving force.”

Once installed, the Davis statue stood nearly twenty-feet, from base to its tallest height. The statue was inscribed with a series of distinctions of Davis, both from his time as an elected U.S. official and later President of the Confederacy, “HE WAS A TRUE AMERICAN PATRIOT,” as if the statement evens out this bitter discrepancy.

For years, the statue comprised the visual high point of the park on the bluff, in a parked named for a battle that happened there only after the war, over the fight for a public memory that served to normalize a continued violent control over African American freedom struggles in public and private spaces alike.

For centuries, the land known as Memphis Park, had been stuck in a turf war around Civil War memory. Its status as a public park within the larger city landscape was predicated on white racial rule. Like so many other seemingly mundane spaces, its history, like its status as a “public” park, had to be invented to commemorate hierarchy and a sense of order.

Confederate Park’s name was changed by city resolution in 2013 (along with the renaming of Nathan Bedford Forrest Park to Health Sciences Park and the nearby Jefferson Davis Park to Mississippi River Park). Today, in Memphis Park, after its rebranding and the removal of the Davis statue, the park and its operators have tried to moved on. But no slate is clean. Entertainment cannot soote, but often fails to outpace the need for remediation reflection.

Protectors of the old ways warn us against the erasure of history, as if the thousands of books, rituals, and policies enacted in the wake of the Civil War go away with the statue. The innovation of history is a defense of the status quo, and a distancing of the past’s imprint on the present.

An actual historical dilemma, I sense in this park and others like it, is how to bulldoze symbols of racial division while marking their removal as part of a longer, ongoing process of dismantling white supremacy.

Protests in support of the removal of the Jefferson Davis statue in Memphis Park, Memphis, Tennessee, August 15, 2017. (Photo courtesy of Andrea Morales)

Protests in support of the removal of the Jefferson Davis statue in Memphis Park, Memphis, Tennessee, August 15, 2017. (Photo courtesy of Andrea Morales)

The longer the removal stays unmarked, and the story of change is not rendered into the park itself, the more confederate apologists can squeeze out a wistful nostalgia of what was, whether on not the pedestal, concrete, or lights remain in place.

The evil of these fabrications of historical memory were that they summoned a lost cause, carved the narrative in stone, and erected them atop the city.

Looking back from the present, we see how the narrative and nature of the park shifted with direct action and profound imagination for change that addressed white supremacy as both a marked and unmarked force of public space: through the long-arc and urgent organizing by activists, especially those of color, who reshaped the place and began to remediate its memory. Tami Sawyer, a driving force of Take Em Down 901, was among its leaders. In August of last year, she was elected to seat as a county commissioner.

From Memphis to Baltimore, New Orleans to New York City, the removal of Confederate monuments and other statues that symbolize the enduring legacies of racial injustice and social inequality are signs of welcome change in how memory politics operate in these distinct locales.

In each case, the shift was underwritten by years of activism and critical art making that troubled the status quo. That struggle continues, both inside municipal bureaucratic structures and organizer-led circles, to change both the content and processes of making monuments. In the meantime, the empty pedestals and concrete slabs that remain offer a strange yet hopeful vantage in their own right. However, if we heed the calls to remove them in the first place, once emptied, we are faced with questions of how to find the appropriate way to proceed.