A promise made with the United States is fragile, at best.

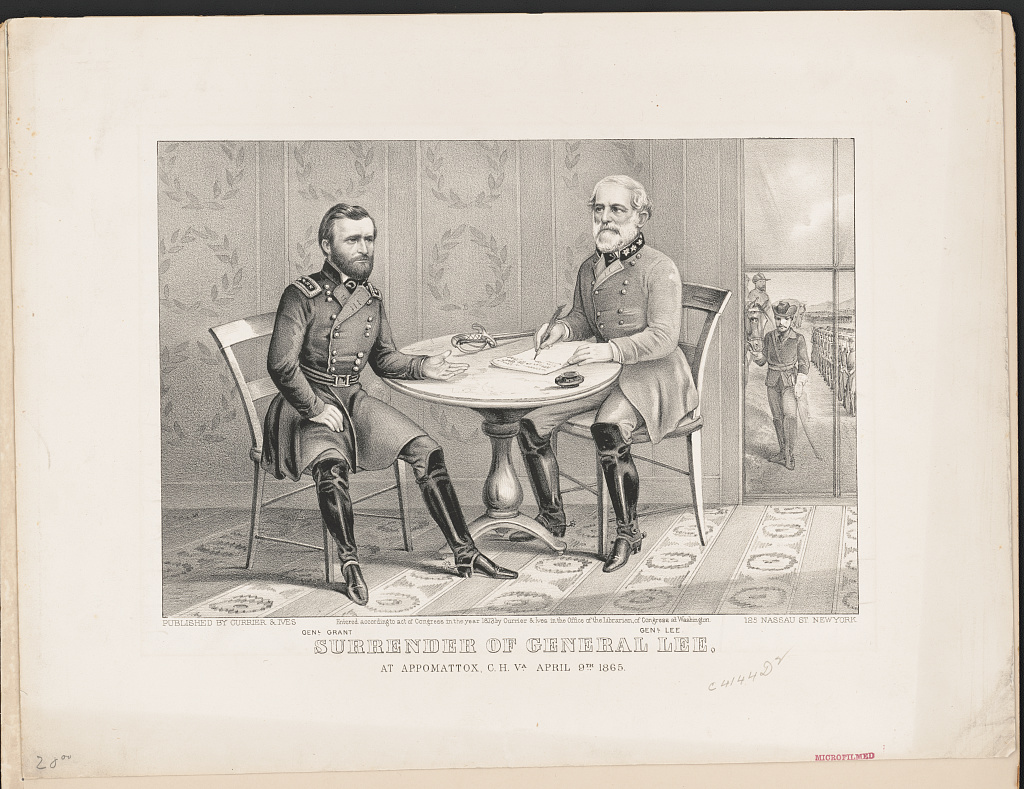

Surrender of General Lee at Appomattox, C.H. Va. April 9th 1865, ca. 1873, Currier & Ives. (Library of Congress)

Histories of the end of the U.S. Civil War often foreground the meeting of powerful men. Widely circulated renderings depict General Lee and General Grant, seated in the room of a manor in the small Virginia village of Appomattox Court House, civilly agreeing to end four years of bloodshed and begin the hard work of rebuilding of a nation.

Yet there are other stories to tell about the end of the war, and other histories left out of the frame. One such story is that of the Confederate Truce Flag: a simple linen dish towel that Lee’s troops brought to the Union Army to signal their surrender.1 The Confederate Truce Flag brought the U.S. Civil War to an end, and yet the magnitude of this cloth has slipped out of public consciousness. In Monumental Cloth: The Flag We Should Know, a new exhibit at the Fabric Workshop in Philadelphia, artist Sonya Clark uses the Confederate Truce Flag as a source of inspiration. Her work provokes visitors to ask how national consciousness might shift if we knew about this symbol of the promise of reconciliation, rather than the Confederate Battle Flag and its affirmation of white supremacy.

Like the Confederate Truce Flag, dominant narratives of the end of the war can obscure the nuance meaning of what occurred that day. As one man recalled some sixty years later, “I was with General Grant when Lee surrendered at Appomattox. That was freedom.”2 These are the words of William Harrison, a formerly enslaved man who accompanied his owner into battle; his recollections were recorded in an interview with the Works Progress Administration as part of the Slave Narratives Project. There is an unknowability of Harrison’s testimony. The transcript of his interview couches reflections of post-war hardships with dubious claims that life was better under slavery, likely reflecting the bias of his interviewer.3Yet his narrative, unreliable as it may be, still conveys an obscured truth about what transpired at Appomattox. The truce—the surrender—represented a seismic, but fleeting, moment of freedom for Black Americans. As historian Nell Irvin Painter observed, “the 1860s had seemed to promise a new and brighter future,” yet by the Compromise of 1877, white supremacy had succeeded in “recapturing the reins of power in the South.”4 Southern politicians called this agenda the Redemption, and with its realization, the expansion of Black freedom closed. The truce was broken.

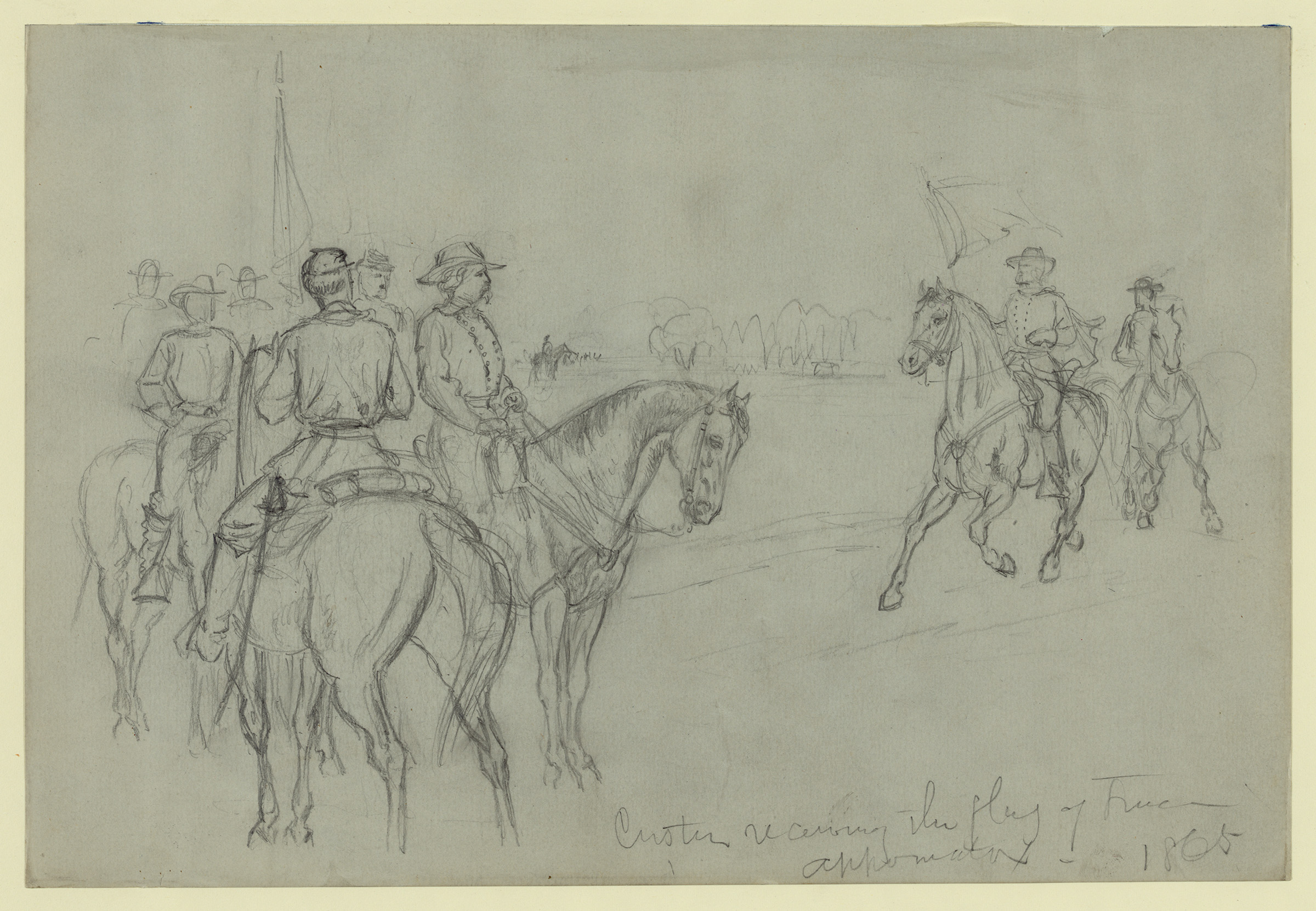

Custer Receiving the Flag of Truce - Appomattox, 1865, Alfred W. Waud. (Library of Congress)

The Confederate Truce Flag did not remain in Virginia after the war. Instead, it was given to Elizabeth B. Custer as a token of appreciation for the efforts of her husband, Gen. George Custer. A man of mediocre achievement (he graduated last in his class at West Point), Gen. Custer managed to ascend the ranks in the Union Army by virtue of his notorious fearlessness in battle.5 Custer was present at Appomattox, and the flag was brought to his lines in surrender. For this, he was rewarded with the relic.

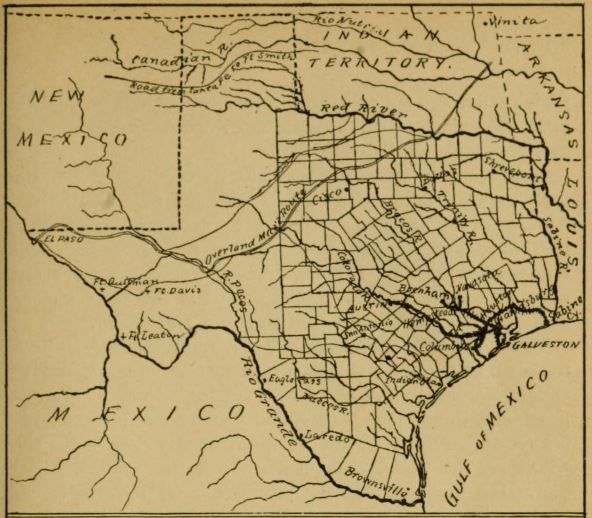

The threat of another war loomed large, this time at the Southern and Western borders against the expansionist visions of Mexico and the imperialist desires of France. In June of 1865, Custer accepted an assignment in Texas, to both see through the Reconstruction agenda under Union occupation and to prevent the outbreak of an imperial war, so he set out for the Southwest with his dutiful wife by his side. Subsequent duties sent the couple throughout the Western frontier, where Custer’s assignments shifted from securing the promise of Black freedom to quelling uprisings of Native nations and establishing outposts of the American empire.

Texas in 1866, illustration from Elizabeth Custer’s Tenting on the Plains; or General Custer in Kansas and Texas. New York: C.L. Webster and Company, 1893, p.19.

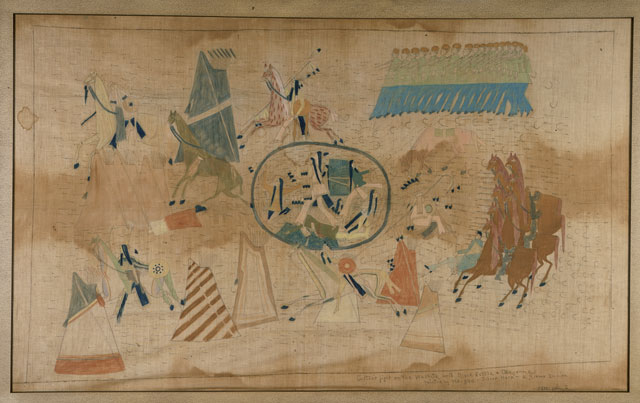

In the late 1860s and early 1870s, Custer led campaigns against the Cheyenne under the orders of General Sheridan. During the Battle of Washita River in 1868, Custer and his cavalry attacked and killed Chief Black Kettle and his wife. They also took 53 Cheyenne women and children captive as human shields during the bloodshed, and the battle resulted in an untold number of Cheyenne casualties.6 By 1873, he had received a new assignment as the commander of Fort Abraham Lincoln, a post established in Dakota Territory a year earlier. The land was home of the Lakota, and their territorial claims stood in the way of Anglo settlement and capitalist ambitions, particularly the expansion of the Northern Pacific Railway. Periodic conflicts over the years escalated to the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876, where Cheyenne and Lakota warriors fought together to kill Custer and defeat his troops. Their victory proved short lived; within a year, U.S. Army forces invaded and took possession of the land.7

Battle of the Washita, 1890, Silverhorn (Kiowa). (The Autry)

After the death of her husband, Elizabeth Custer returned home to Michigan before settling in New York. She spent the remaining years of her life mythologizing her late husband, and reflected on their life together in memoirs like Tenting on the Plains: General Custer in Kansas and Texas.8 In the books, she failed to mention whether the Confederate Truce Flag accompanied their westward journeys, but she did maintain ownership of it as a prized possession. She loaned the flag to the Smithsonian Institution in 1912, and it is mentioned in their annual reports alongside her other donations: the table upon which General Grant wrote the terms of the Confederate Army’s surrender, and her husband’s helmet and coat from his genocidal Western campaigns.9

*

A promise made with the United States is fragile, at best. Just ask any of the other hundreds of sovereign nations on this land. When we encounter our intertwined, uneven histories—of Reconstruction and Redemption, of freedom and genocide—then, and only then, can a truce be meaningful.