The following excerpt is from Robert Slifkin's new book, THE NEW MONUMENTS AND THE END OF MAN: U.S. Sculpture Between War and Peace, 1945-1975. The book considers how American artists reflected on the fate of humanity in the nuclear age through monumental sculpture.

David Smith, Oculus, 1947. Painted steel on wood base, 321⁄8 × 37 × 75⁄8 in. (81.6 × 94 × 19.4 cm). Private collection.

One of the fundamental characteristics of the monument is its Janus-faced temporality, the way that it simultaneously looks backwards to an event or figure from the past and imagines its material preservation into an unspecified future. One might say that monuments, through their characteristically commanding physical presence and occupation of space, aim to continuously transmit a message into an unknown and ever-expanding future. In this regard, monuments, at least as they have been traditionally understood, are fundamentally conservative objects, seeking to shape the future, not through revolutionary action, but aspiring for the more moderate promise of constancy, both material and mnemonic, within the inevitable flux of time.

Consequently, a modern monument is, as Lewis Mumford suggested, something of a contradiction and even the most ostensibly contemporary monument risks possible obsolescence, irrelevance and unintelligibility as it perseveres in an environment that is bound to change both materially and ideologically.1 Robert Musil would acknowledge this non-synchronous dynamic between the avowedly timeless monument and the rapid pace of modern life in a short, witty essay on the subject from 1927 in which he provocatively claims that there are few better ways to render a figure or event obscure than to erect a monument in its honor. Musil’s canny recognition of the monument’s dialectical affinity with oblivion—the very thing it is built to defy—in many ways set the terms for a counter tradition of monumentalism—or anti-monumentalism—that has emphasized ephemerality, contingency, and critique over such conventional values as permanence, universality, and celebratory heroism.

Theodore Roszak, Spectre of Kitty Hawk, 1946–47. Welded and hammered steel brazed with bronze and brass, 40. × 18 × 15 in. (102.2 × 45.7 × 38.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase. (16.1950)

David Smith, False Peace Spectre, 1945. Painted steel and bronze, 12½ × 27¼ × 10¾ in. (31.8 × 69.2 × 27.3 cm). Private collection.

This postmodern and post-medium renewal of sculptural monumentalism emerged in the mid-1960s (the moment, when as Rosalind Krauss has argued, the tenets of modernist autonomy gave way to an array of practices that engaged with the contingencies of site) in the work of artists like Dan Flavin, Claes Oldenburg, and Robert Smithson, who produced nominal, if fundamentally ironic, versions of the form. Unlike traditional monuments that sought to preserve the memory of historical events or actors into the future through their material permanence and imposing scale, these new monuments, to borrow Smithson’s designation, seemed to compromise their commemorative function by disavowing a commitment to perpetuity. Whether because of because of their colossal size which made them impossible to build (Oldenburg) or their ultimate fate to become obsolete because of technological development (Flavin) or disappear due to geological phenomena (Smithson) the new monumentalism registered a temporal paradox: “Instead of causing us to remember the past like the old monuments,” Smithson wrote, “the new monuments seem to cause us to forget the future.”2

Smithson would align this paradoxical future-orientated oblivion conveyed by these new monuments with the concept of entropy, arguing that the typically bland, geometric forms associated with the new sculpture served as material auguries of an all-encompassing sameness that would, according to the Second Law of Thermodynamics, ultimately inflect the entire universe. (A drive down any suburban highway indicates the prophetic force of Smithson’s assessment, delineating to a fateful trajectory that leads from a minimalist box to a chain box store, both of which, according to the artist’s theory, foretell a forgettable future of cultural monotony and cosmic extinction.) Replacing the quasi-universal laws of metaphysics with the physical laws of the universe Smithson established a materialist teleology that, much like conventional examples of monumentality, provided a means to synchronize a contemporary audience’s experience of space and time onto a much broader historical continuum.3

David Smith, False Peace Spectre, 1945. Painted steel and bronze, 12½ × 27¼ × 10¾ in. (31.8 × 69.2 × 27.3 cm). Private collection.

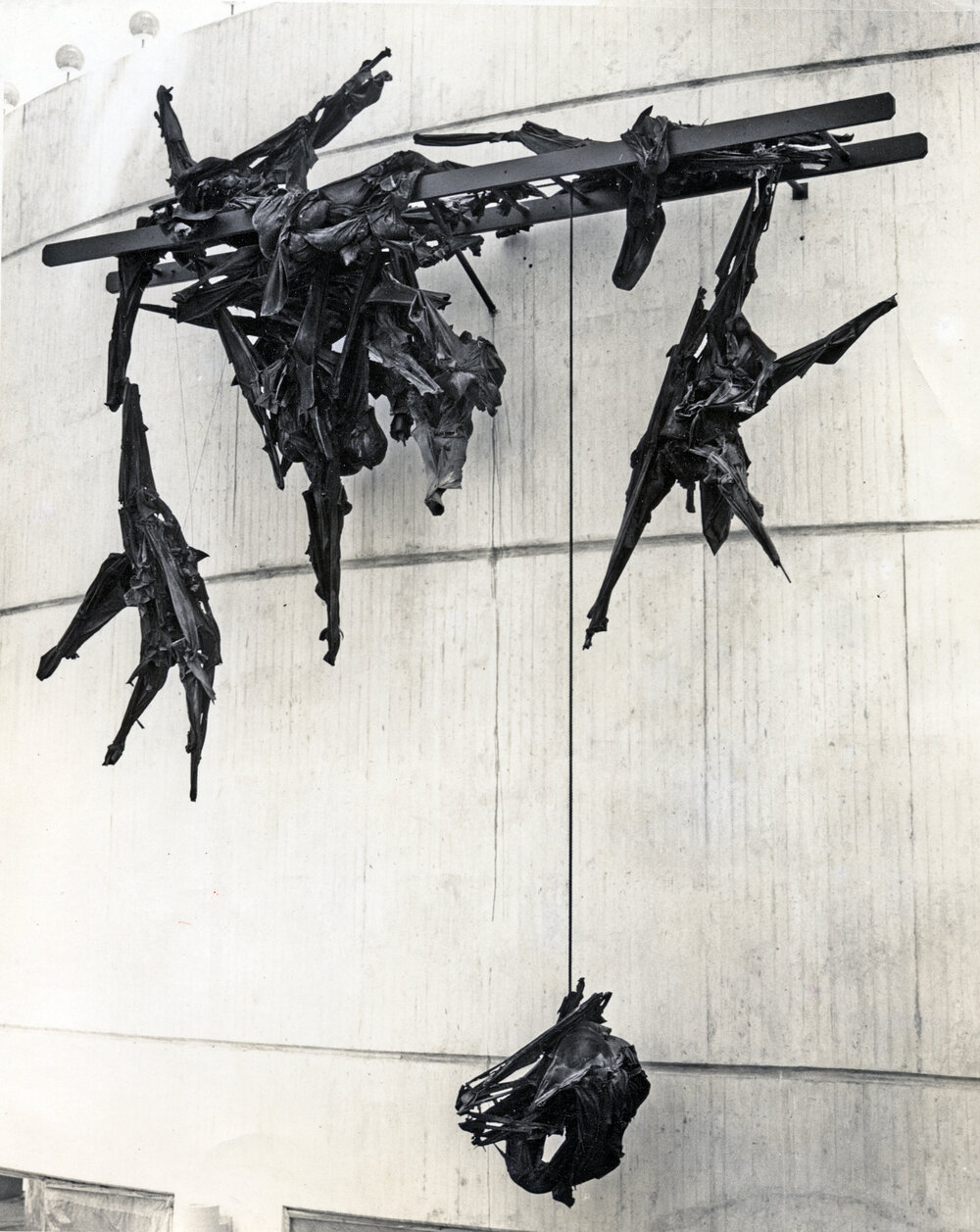

Dennis Oppenheim, Decomposed MOCA, 1969. Building construction materials. Five piles of raw materials, ingredients of the building, distributed on the floor in piles equal to the artist’s body weight. Each week the museum contacts the artist by telephone. Piles of insulation, sawdust, gypsum, cement, and metal filings then adjusted according to his exact weight reported at the time of the call. Installation at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, 1969.

If Smithson’s conception of the inevitable entropic oblivion that awaits all forms on monumentality—and human endeavor more generally—might appear nihilistic or unexpectedly romantic (however valid or even visionary it may seem in the face of the existential implications of climate change) it also presents a paradigm for a monumentalism that is able to register the contingencies of experience and the discontinuities and multiplicities of history and, perhaps most importantly, repudiate the promise of permanence and possessiveness that has made the monument so ideologically problematic for a radical, let alone progressive, politics. Recent intimations of this sort of entropic monumentality can be discerned in Thomas Hirschhorn’s Gramsci Monument (2013) and Kara Walker’s A Subtlety (2014) in which the dynamics of commemoration and ruination operate in tandem, so that multiple publics are assembled and various meanings are generated without recourse to a rhetoric of universalism or timelessness. Amidst the current debates concerning which existing monuments should remain standing and which should be sent off to oblivion (or at least rendered less ideologically potent through their archivization in museums) works like these posit an alternate vision of the form, one in which acts of remembrance exist alongside opportunities for contestation. By proposing the necessity of an expiration date for all examples of the category, these works propose an ethics to the monument’s characteristic temporal expansiveness, one whose ultimate message is not so much remember this as keep going. 4

From THE NEW MONUMENTS AND THE END OF MAN: U.S. Sculpture Between War and Peace, 1945-1975 by Robert Slifkin. Published by arrangement with Princeton University Press. Copyright © 2019 by Robert Slifkin.