This is the first essay in a three-part series engaging with work from theorists on contested memory and diasporic black geographies. In this piece, Monument Lab Graduate Researcher Hilary Malson examine silence as an action in the production of history. In the subsequent essays, Malson will explore forgetting, counterhegemonic modes of remembering, and new ways of knowing.

James & Son, Women Walking from Africville Towards Halifax, on Campbell Road near Hanover Street, 1917. (Nova Scotia Archives Photo Collection)

Syncopation

Def. the rhythmic accent on an off-beat; the heart of jazz; the counterpoint.1

“I am the sugar at the bottom of the English cup of tea. I am the sweet tooth, the sugar plantations that rotted generations of English children's teeth. There are thousands of others beside me that are, you know, the cup of tea itself. Because they don't grow it in Lancashire, you know. Not a single tea plantation exists within the United Kingdom. This is the symbolization of English identity — I mean, what does anybody in the world know about an English person except that they can't get through the day without a cup of tea? Where does it come from? Ceylon – Sri Lanka, India. That is the outside history that is inside the history of the English. There is no English history without that other history.” 2

—Stuart Hall, 1991

In his pivotal work Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, Haitian historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot draws from the buried histories of his homeland to demonstrate how power is exercised through the production of national narratives.3

Trouillot focuses his attention on the many impossibilities of the Haitian Revolution. He argues that the uprising itself was a direct affront to French and European conceptions of black humanity, and links that to the ongoing exclusion and subordination of Haiti in world systems today. That enslaved Africans could envision their own freedom and collectively rise up to overthrow a colonial government and create a new country was unthinkable, even among the European left. Thus, the first successful national slave revolt was thinly referenced in the historical records of the moment, even as it unfolded, and it remains outside the frame of contemporary dominant discourse on the Age of Revolutions.

Jacob Lawrence, The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture Series: The Burning, Aaron Douglas Collection, Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana, 1938. (Christie’s)

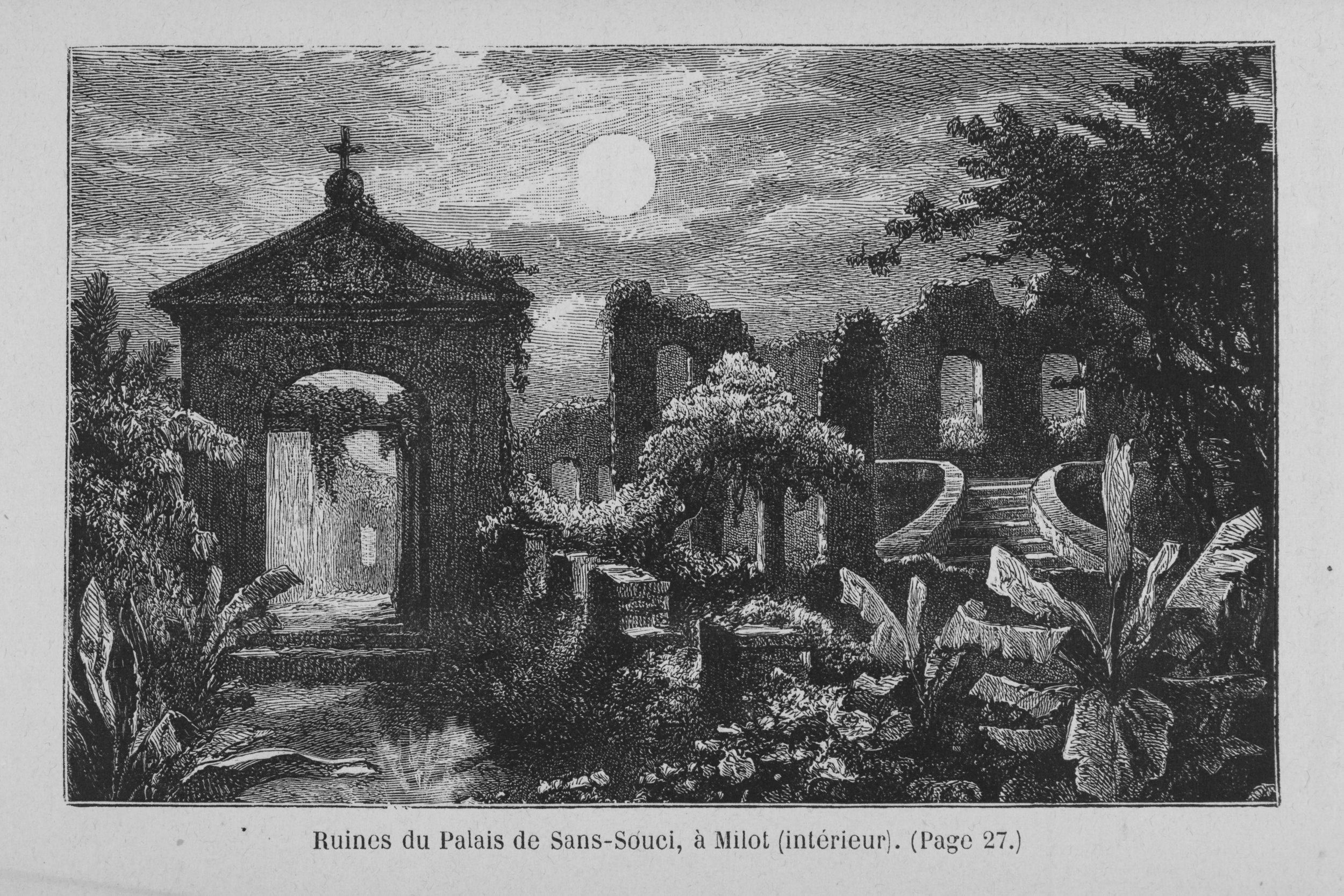

Trouillot also reveals how the narratives surrounding the Haitian Revolution were twice-silenced: initially by the world beyond Haiti’s borders, and then internally, through the active silencing of complicated events by generations of Haitian historians. He excavates how the physical conquest of Sans Souci, a man whose defiance disrupts linear narratives of the Haitian Revolution, was written out of the historical record. Jean-Baptiste Sans Souci, a rebel leader among factions of black Haitians, was killed by Henry Christophe, his rival who went on to become the first King of Haiti. In the years following Christophe’s rise to power, he erected a palace in the northern mountains of Haiti — perhaps on the very site of the assassination — and named it Sans Souci. At the time, the expansive palace was unparalleled in size and opulence, and the remnants of the structure continue to attract the attention of tourists and historians. The intent behind the palace’s name remains uncertain, as few of Christophe’s records survive, but Trouillot suggests that Christophe may well have symbolically named the palace to commemorate defeating his rival. However, few Haitian historians publicly connect the two Sans Soucis. Their investment in cultivating and sustaining a narrative of victorious defeat over colonization and slavery has pushed inconvenient events to the margins. Today, Christophe looms large in the national imagination as a ruthless leader, while his challenger has been relegated to the footnotes of history.

Events like the Haitian Revolution and the assassination of Sans Soucis are not passively forgotten; they are actively silenced. Historical production occurs as events are transformed into facts, and it is through the creation, collection, interpretation, and resonance of these events-as-facts that power is exercised. For nationalist historians, Christophe’s glorious success over the French rendered the threats posed by his rival Sans Souci a mere distraction to the overall narrative. As Trouillot succinctly declares, “Christophe beat the French; Sans Souci did not. Christophe erected these monuments to the honor of the black race, whereas Sans Souci, the African, nearly stalled the epic.”4 Nestled in the mountains of Haiti, remains of the palace still stand. These ruins are publicly recognized as evidence of one history, but they are also the haunting of another, lingering beyond the sphere of possibility.

Ruines du Palais de Sans-Souci, a Milot (interieur), Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, 1888. (The New York Public Library)

There is much discussion occurring at the intersection of erasure and collective memory, which geographer Kenneth Foote frames as the ways in which “individuals and organizations act collectively to maintain records of the past.” 5 In his examination of collective memory following the communal violence perpetrated in colonial Salem, MA and the Jewish genocide in Berlin, Foote observes how local contemporary communities have negotiated sustaining or effacing memories of those events. Spatial evidence in both cases have been obliterated. In Salem, local shame surrounding the witchcraft trials contributed to the disappearance of execution records, which has resulted in uncertainty regarding the precise location of the hangings; yet, 300 years later, the legacy of the trials remains in public consciousness, and the loss of life has been monumentalized. Meanwhile, though buildings in Berlin associated with the Third Reich were destroyed, that movement was accompanied by a strong public push for memorialization of the Holocaust.

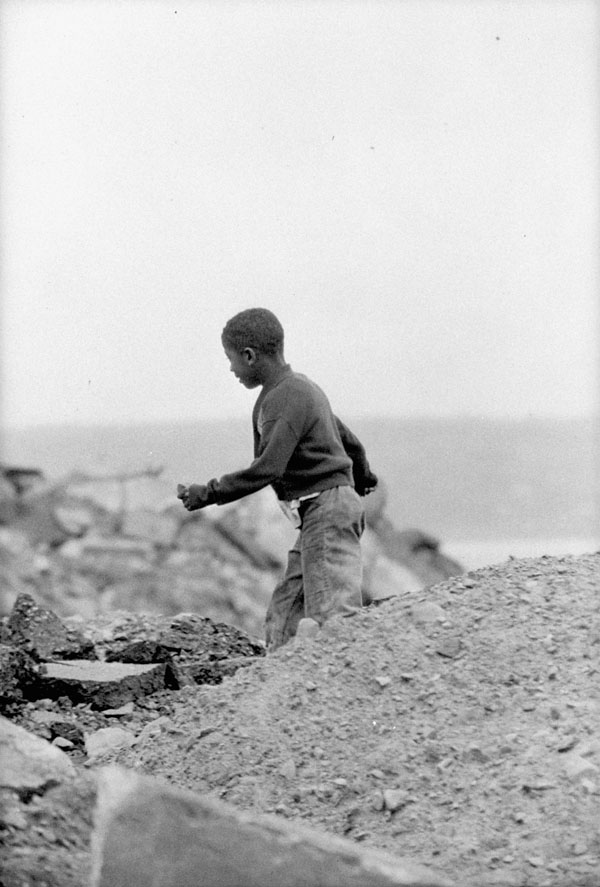

Yet the ongoing dispossession of black life by the state demands a distinct set of analytical tools for examining spatial erasure. As geographer Katherine McKittrick writes of Africville, the historic black community of Nova Scotia razed in the 1960s, commemorative gestures, such as the creation of a historic marker, inadequately challenge the “Otherness” of blackness in Canadian history.6 That Africville is continually heralded as the exception to that narrative — that it is nationally understood as the site where blackness was demolished, rather than as one contestation in an enduring struggle of emplacement — underscores what McKittrick deems the “absented presence” of black Canada. Scores of evidence, in the form of slave burial grounds, anti-black surveillance laws, unmistakable spatial namings such as Nigger Rock and Negro Creek Road, and the near total burning down of Montreal by an enslaved black woman named Marie-Joseph Angelique, disappear from the record through relocation, renaming, burying, and formalized forgetting. These acts of effacement all work in tandem with the continual constitution of Canadian blackness as recent, as urban, and as immigrant; histories suggesting otherwise represent an impossible disruption to the national narrative. To return to Trouillot, “the ultimate mark of power might be its invisibility; the ultimate challenge, the exposition of its roots.”7

Ted Grant, Africville – Black Community – Young Black Boy, Halifax, Canada, 1965. (Library and Archives of Canada)

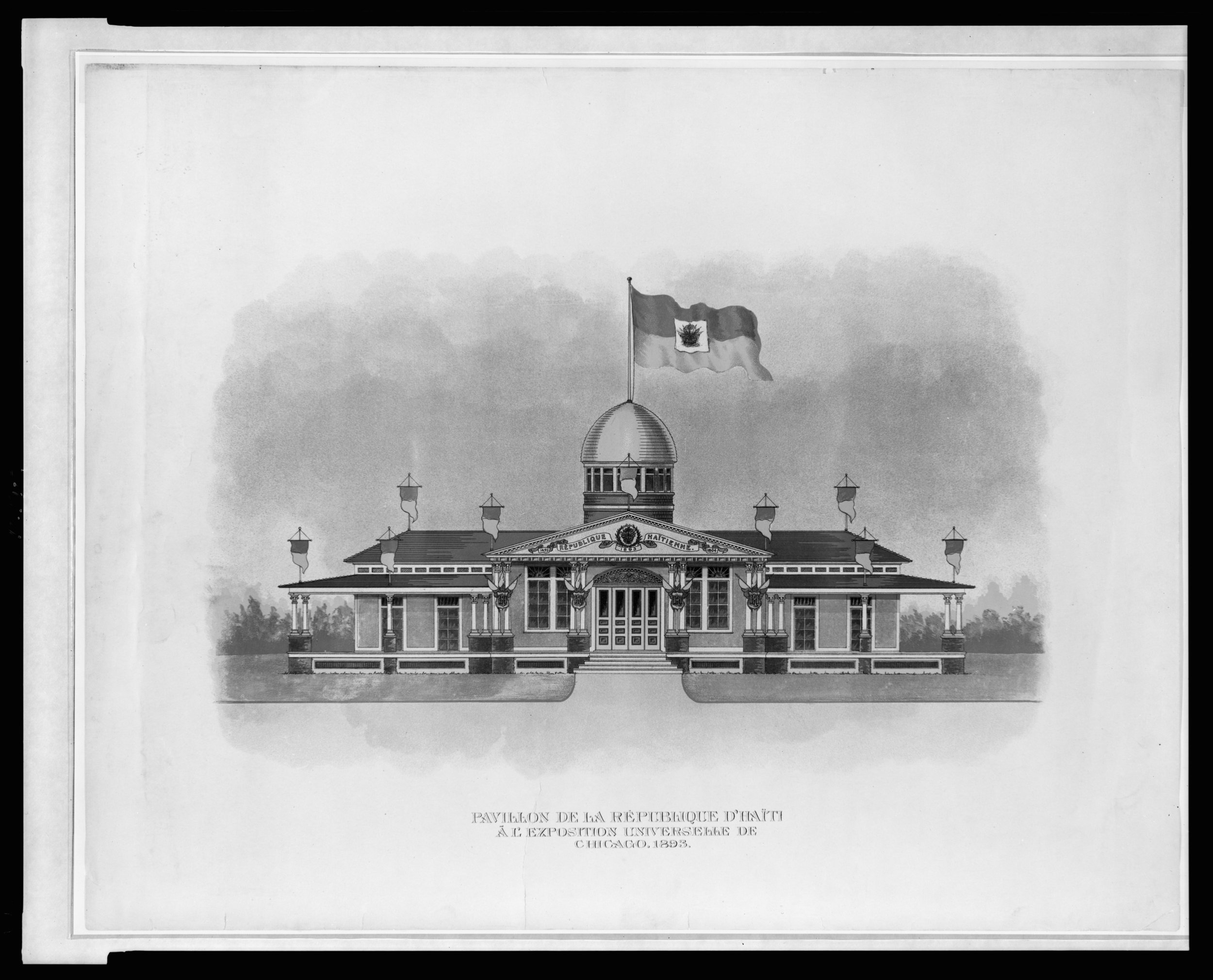

The World’s Fairs of the 19th century encapsulate an extreme of nationalistic fervor, and yet black people exploited openings in these affairs to upend representations of the nation. While an array of non-white people were put on display as embodied evidence of humanity’s lowest ranks, a small, but sizeable contingent of black intellectuals seized the opportunity to craft counternarratives.8 In the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, for example, a group of scholars led by Ida B. Wells protested the formal exclusion of black participants by issuing a pamphlet decrying their exclusion, which they distributed with the support of the Haitian delegation.9 As Frederick Jackson Turner championed the successful realization of manifest destiny, they exposed the hypocrisy of American exceptionalism on the world stage by crying out against lynch law, segregation, and the persistent devaluation of black life.

Pavillon de la République d'Haïti à Exposition Universelle de Chicago, 1893. (Library of Congress)

Stuart Hall was right. There is no English history without the co-constituted histories of Sri Lanka, Jamaica, and the other corners of the world where children interpret their dreams in a colonial tongue. Yet dream they do, and it is in the contours of their dreams, their imaginations, their actions that new ways of knowing and being are possible. Drawing from Amiri Baraka’s study of jazz and the blues, diaspora studies theorist Rinaldo Walcott critiques the reification of jazz from a style of doing to a rigid form. He writes, “jazz as noun cannot possibly alter America; as verb, possibilities exist.” 10 In the production of history, the counterpoint to hegemonic power beats on.

Are you listening?