When I was a kid, my public school teachers often asked me to identify “my personal hero”. I didn’t understand this prompt because I didn’t elevate people to pedestal stature like that. I disliked the idea of lauding one person over another and was troubled by what I witnessed at the time as the privilege of being seen. This seemed to dismiss the simple heroism in the everyday and to simplify collective experience and labor. Perhaps it was one of my first mini-protests, opting out of hero work. Eventually, I chose Harriet Tubman and later Rosa Parks. I thought they were courageous and graceful, though I still didn’t find comfortable the position of the hero.

Looking back, this discomfort emerged from an early recognition of the injustice in the ways our society and culture curate stories into the collective consciousness, remember together, and value contribution. Growing up as a Muslim-American in a blended, immigrant family, I found that the stories to which I may have related were not visible in my landscape. I knew that it mattered which life experiences we shined a light on, where we shared them, and how.

|

|

Heroes

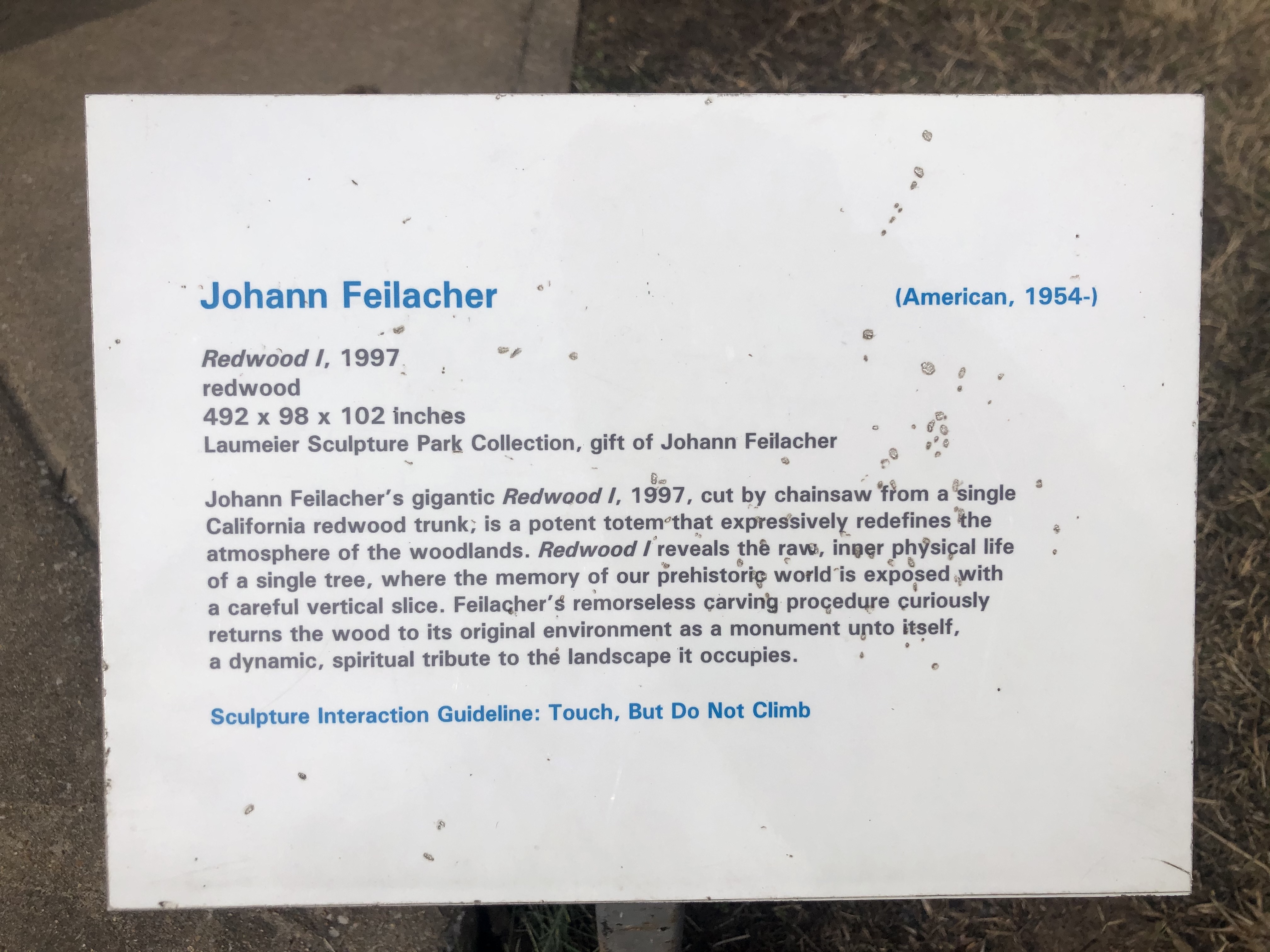

Most of the time when I have a casual conversation with someone about monuments, the assumption is that we are talking about commemorative battle victory emblems or, more commonly, statues. Statues often depict an individual person who was a leader or whom we should deem a hero. I’m guessing this is the assumption because these are what many of our popular monuments depict. But, there are many monuments that do not depict people, like Karyn Olivier’s The Battle Is Joined, Nicholas Galanin’s Shadow on the Land, an Excavation and Bush Burial, and The National Memorial for Peace and Justice. Just the other day I walked by Johann Feilacher's Redwood I wherein a preserved cut of a redwood tree is a monument unto itself.

These conversations usually turn to discuss which individual ‘heroes’ we lift up, and which narratives or histories we choose to center. These heroes typically revolve around some sort of battle — civil or physical — and often the most provocative thing someone might say is that the winners write history. However, many other powerful and significant stories slough off when we center on the individual hero. We miss the stories of the people who contribute more quietly to making change happen. Individualism is too often a dangerous cultural lens that is assumed in how we tell stories of the past. I’m interested in how monuments themselves challenge this cultural framework that glorifies a singular saviour instead of the collective.

How can monuments help us remember our connected humanity and challenge the notion of the individual hero? How can they push us to grapple with the complexity of shared, emergent and inconclusive collective memory?

In a 1962 essay titled “The Creative Process”, James Baldwin wanted us to learn that this is the delicious role of the artist.

“The entire purpose of society is to create a bulwark against the inner and the outer chaos, literally, in order to make life bearable and to keep the human race alive. And it is absolutely inevitable that when a tradition has been evolved, whatever the tradition is, that the people, in general, will suppose it to have existed from before the beginning of time and will be most unwilling and indeed unable to conceive of any changes in it. They do not know how they will live without those traditions which have given them their identity. Their reaction, when it is suggested that they can or that they must, is panic. And we see this panic, I think, everywhere in the world today... A higher level of consciousness among the people is the only hope we have, now or in the future, of minimizing the human damage... Society must accept some things as real; but the artist must always know that the visible reality hides a deeper one, and that all our action and our achievement rests on things unseen. A society must assume that it is stable, but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven."

In the context of memory objects, Baldwin calls us to ever-evolve a tradition of reflexive monument-making and cultural hegemony. Change in either, he suggests, will be uncomfortable as we have dug our identities out of this clay. We see this in how many express a fervent impossibility to imagine other histories apart from those of Confederate sacrifice. It is explained often as a personal affront to a sense of self, a curious way for both historical stories and memory objects to deepen a claim to a past or a commitment to an aesthetic or form.

The question is, then, what is the relationship between art and societal change? Are artworks themselves capable of changing our shared values and cultural hegemony, or do we make art that responds to or depicts our cultural shifts, that pushes against it, celebrates it, questions it? Where does the cycle start? Put another way, how might the experience with a monument change the way we understand what we collectively value — or is the monument’s role to tell the story of what we collectively value? If “the visible reality hides a deeper one”, as Baldwin says, then the artist is tasked to both evolve culture and evolve the form and content of the artworks in the public realm — perhaps the spark of change happens anywhere and the relationships between culture and art, art and culture are completely cycling, inseparable.

My childhood impulse to challenge individualized heroes shaped how I practice art. It led me to a desire to instill a cultural shift towards collectivism. Is our shared and interconnected labor to make change happen the deeper reality to which Baldwin alludes? If there remains a continuum between art and cultural change, what lessons would we glean, and how would we contour our future around this narrative of the past?

I want the monuments of the future to look like the celebration and remembrance of communal labors. I long for multiplicities and communities to be understood as heroes. This commands us to listen in a new way, to evolve in our understanding of labor, reconsider ‘success’ and to believe in an alternative theory of change. For me, that theory calls everyone into imagining the kind of world they want to be in; not waiting for a figure. We are the ones we have been waiting for, after all.

In Public Space

The context of public space can be particularly insidious. Public space is like this water that we wade through every day, and we are always absorbing something, always exchanging. What are the stories that (literally) surround us and enwrap our lives? These matter. What takes up space matters. It crafts our culture and our realities. It reinforces or calls into question. I am ready to imagine a time in which we memorialize mutual aid in the time of COVID-19, the collective labor that brought about a change in political power, the cooks in the kitchen that powered the revolution.

Not only can monuments help us re-engage with history, but also offer a proposition towards a future. As we react to and interact with these artifacts, we notice that we change. This is the moving work, to notice your reactions, to notice your change, to notice our reactions, to notice our change. If we are changing, then we must change. Sometimes we say goodbye, sometimes we rearrange, sometimes we melt and recast and even other times we create ever-new forms, but always from something.

Why don't we honor that we do not do this alone?