Fig1: James Walker, City Commissioner Gillem, Ralph E. Lum, Gutzon Borglum and the Monument’s base. (Source: Newark Evening News, Sept 4, 1925)

Nobody talks much about the bases on which public statues and sculptures stand. This is perhaps unsurprising. Unless elaborately decorated or inscribed, they are usually considered subordinate to the works of art they raise. They’re not expected to possess a content of their own or distract from the object of elevation. For this reason, they tend to be rather plain. Their role is primarily functional not aesthetic, and to suggest otherwise risks misinterpretation or being accused of slightly missing the point.

Yet, in the past two years or so, empty plinths and pedestals are becoming an increasingly common sight. As public statuary to the Confederacy is slowly being removed in various cities across the United States, these now prominently placed blocks of stone have become capable of being interpreted symbolically – signifying the erasure of history for some or a historical victory for others.1 This new attention to the sculptural base challenges the neutrality often assumed of it. It leads us to question their role and worth, as well as the materials from which they’re made.

At Military Park in downtown Newark these questions are particularly pressing. Located at the park’s center is a large bronze monument raised on a granite base. It’s called Wars of America and was created by the artist Gutzon Borglum at the beginning of the twentieth century. At the time it was lauded as “one of the largest bronze monuments in the world” as well as the “first monument in America to depict mass action.”2 Few commentators, however, paid attention to its base.

At first glance, it does appear fairly generic. It is made of a light-grey granite, a material commonly used for propping up sculptural displays due to its durability and strength. From the average gravestone to some of the country’s more commemorative forms, this type of stone can be found in multiple places and contexts.

Fig 2: Close-up of Granite base.

In this instance, the stone’s source, rather than its destination, lends the base added significance. The rock used for Borglum’s monument derives from Stone Mountain, a large isolated granite dome located in the north of Georgia. The Mountain is famed not so much for its exports but for the symbolism of the site. Once a sacred gathering place of Pueblo-Indian groups before their forced removal by white settlers, it is closely associated with White Supremacy.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the mountain’s owner, Sam Venable, granted easement to the Ku Klux Klan to host their revival there in 1915. At more or less the same time, Borglum was commissioned to carve a colossal monument to the Confederacy into its bare cliff face —"Confederate Memorial seized upon by Klan as Huge ‘Ad,’” the New York Tribune declared. By the middle of the century, the link between the Mountain and White Supremacy had been secured. “Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia,” Martin Luther King proclaimed in his famous speech, firmly locating it within the history of racial oppression.

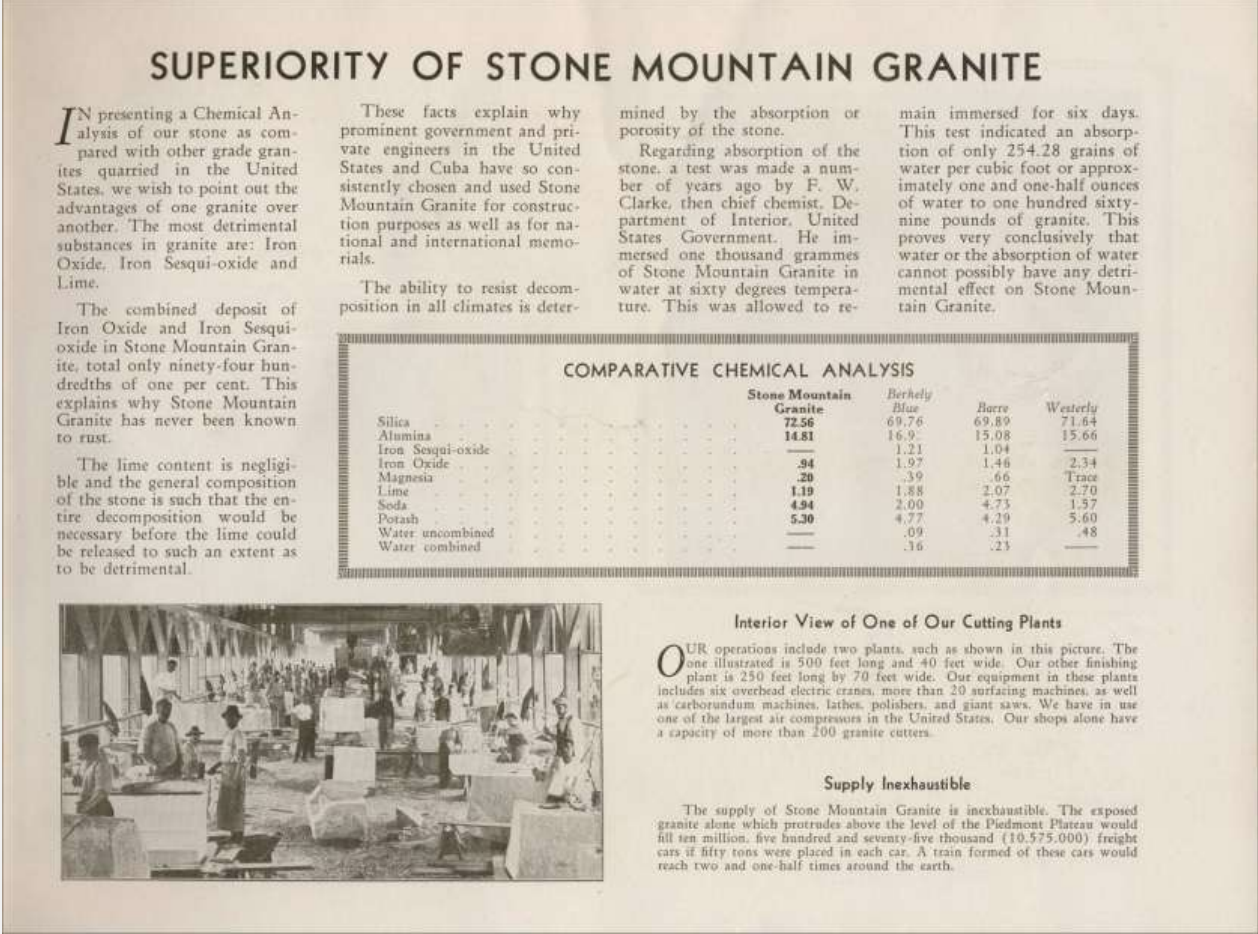

Fig 3: ‘Superiority of Stone Mountain Granite’. (Source: Southeast Granite Company—Stone Mountain Memorial/Monumental Stones Catalog (c.1920s))

The Stone Mountain trade catalogue further encourages cultural connections between the stone’s source and White Supremacy. In addition to the assurance of “a material of flawless, everlasting quality,” it states that prospective buyers will also receive:

“added comfort and satisfaction in the knowledge that the monument that marks the spot so sacred for him is of the self-same stone as the greatest memorial on earth—that it will last as long as Stone Mountain itself and make the memory of his loved ones as enduring as the fame of the immortal Lee.”

The use of Georgian granite in Newark is even more notable when we consider the city’s proximity to its competitors. Previously granite from New England had been used in the bases of the park’s monuments. The stone raising the Spanish War canon, for instance, derives from Vermont. Along with Massachusetts, this region was particularly renowned for its granite industries making the transportation of sixty-three tons of stone from Georgia all the more suggestive of symbolic intent.

In addition to the stone, the sculptor also connects the two sites. In 1915 the United Daughters of the Confederacy commissioned Borglum to carve the sculpture of Confederate General Robert E. Lee on Stone Mountain. The duration of this project overlapped with his activities in Newark, as various newspapers such as the Omaha Bee made clear [fig 4].

![Omaha+daily+bee.+(omaha+[neb.]),+28+may+1922.+chronicling+america +historic+american+newspapers.+lib.+of+congress.+<https Chroniclingamerica.loc.gov Lccn Sn99021999 1922 05 28 Ed 1 Seq 42 >](https://data.monumentlab.com/uploads/monument-lab/originals/e10f059e-93bc-4811-ab74-2925e5a2ba72.jpg)

Fig 4: Omaha Daily Bee, May 28, 1922. (Source: Chronicling America, Library of Congress)

Similar in material as well as theme, both the Stone Mountain memorial and Wars of America speak to a particular version of American history that prioritizes whiteness. No black soldiers are featured in Wars of America, despite their contribution to the conflicts depicted. Likewise, the Stone Mountain memorial, as with any monument to the Confederacy, presents a narrative of the Civil War that privileges white reunion over black emancipation, denying the centrality of slavery as cause.

Yet, the memory of slavery was not altogether absent from Borglum’s scheme. Art historian Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby argues that the sculptor repeatedly “emphasized the need to invent technological solutions to compensate for the loss of ancient Egyptian slavery.” The comparison, she concludes, was euphemistic: “the slavery no longer available to Borglum was black slavery. If ancient Egyptian monuments provided a comparative measure for modern colossi- ancient Egyptian slavery served as a way for Americans to speak about the loss of slavery after the Civil War.”3

To be sure, Borglum’s involvement in the Confederate monument project places him at the center of Klan-related activities that occurred there. He was close friends with the Grand Dragon D.C Stephenson, and their correspondence reveals shared racist and xenophobic views. Yet, the artist also denied he was a member of the Klan. He called his son Lincoln, not Lee, and he frequented the political salons of Washington, dining with key figures of American liberalism such as Walter Lippmann, Oliver Wendell Holmes and the future Justice Frankfurter.4

When considering the extent to which the granite base at Newark is implicated in the history of racial oppression, these facts are not irrelevant. In Art History, often when we attempt to locate the meaning of an artwork we look to the artist’s intentions, previous projects, or political inclinations for clues. Borglum seems to elude us here. How do we make sense of a sculptor who builds monuments to Lincoln and Lee, to the Confederacy’s vice-president Alexander Stephens, as well as to the immigrants Sacco and Vanzetti? What is it that makes the Stone Mountain memorial and Mount Rushmore compatible?

Such range might give the impression of apoliticism, but this would be misleading. It would be far more accurate, or rather more important, to ask what makes the American political system so accommodating of racist views. One explanation might rest on a definition of ‘freedom’ as the denial of enslavement, including its memory and legacy. Another might call attention to the history of black disenfranchisement and barriers to democratic participation that continue to impact US politics today. Ideological contradictions are often tolerated when they serve the interests of those in charge. Borglum’s monuments imagine a nation that is similarly selective and promulgates White Supremacy as a result.

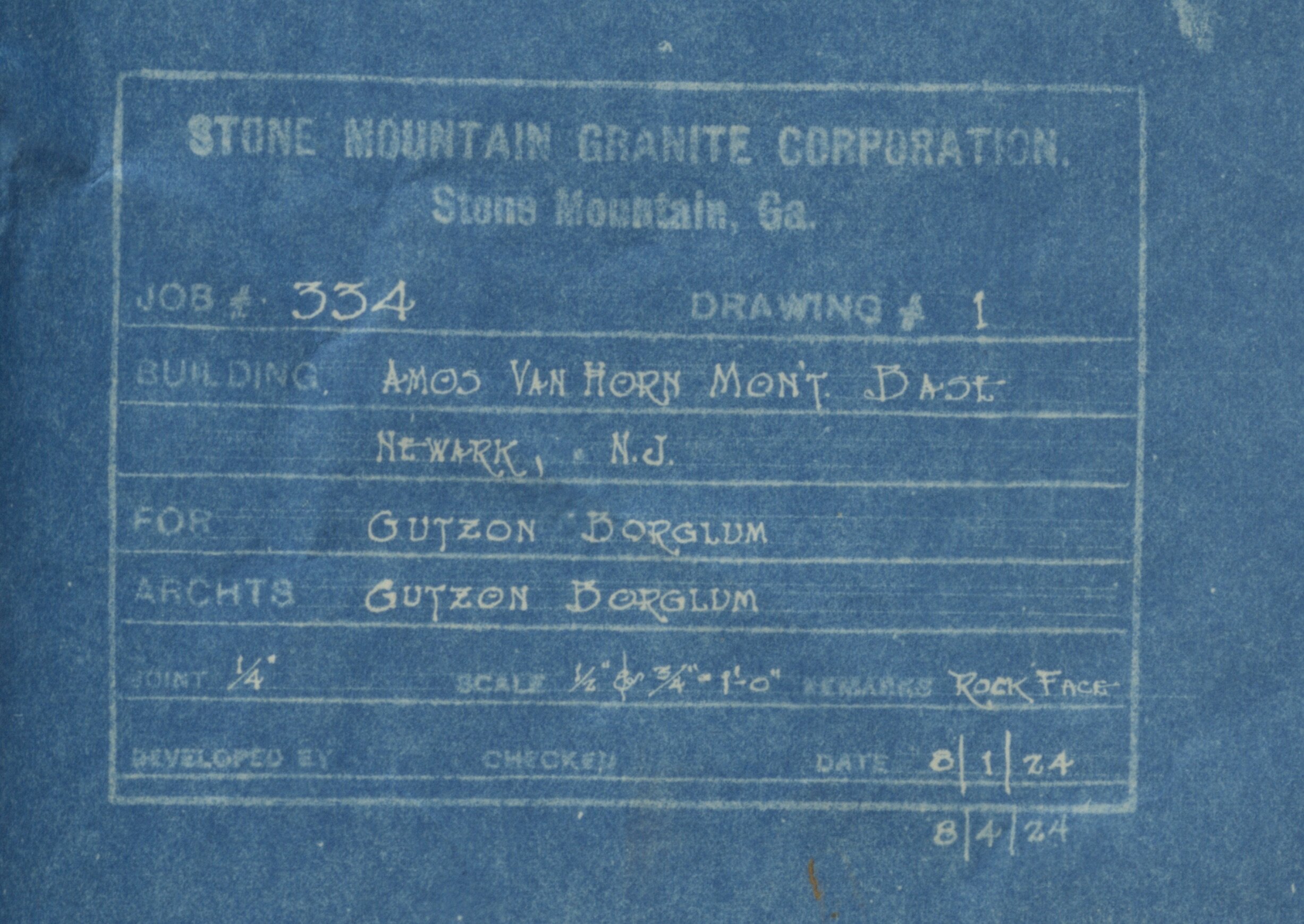

Fig 5: Blueprint with Stone Granite Corporation Imprint. (Source: Gutzon Borglum Papers, Library of Congress, (Box 129—1.4)).

That the Newark monument is morally troubling is undeniable from this perspective. Feeling unease when we learn of the stone’s origin and the political inclinations of the sculptor points to the far larger system of oppression that has been institutionalized. Borglum’s personal commitment to White Supremacy is inexcusable, but the singularity that defines the relation between author and work should not detract from the culpability of this wider context. The problem of White Supremacy is structural, like the monument’s base.