A mobius strip is a one-sided flat surface with one boundary curve. It is created by taking a two-sided flat strip and twisting it around so that the far ends touch. This twist reduces two sides to one, creating an infinite loop. When rendered in three-dimensional space, the strip can appear as an infinity symbol or much like a loose rubber band. If one were to walk the full-length of the loop, they would return to the starting point having traversed both sides of the surface, all without crossing an edge. This is how Canadian artist Aiyyana Maracle (1950 - 2016) conceptualized gender. Breaking away from the modern social construction of a gender binary, she saw gender as an infinite loop on which we constantly traverse varying degrees of masculinity and femininity. This way of understanding and expressing gender offers a freedom to exist as an organic being —free to grow, free to change, free to move. Maracle used this concept of gender to create Gender Mobius, a performance piece, that sought to offer publics new ways of understanding gender and its relation to colonial power.

Aiyyana Maracle was a multidisciplinary artist, curator, and educator who was known for her experimental performance pieces. She identified as a “sovereign Haudenosaunee woman,” a keeper of her culture, and as a “transformed woman who loves women.”1 Sovereignty is a political term used to assert one’s supreme authority, either over a state, or as it is often used in Native Studies, over one’s self. Gender Mobius, one of Maracle’s definitive performance pieces, premiered on June 3, 1995, at the Halfbred Performance Festival in Vancouver, Canada.2 The festival was co-organized by Maracle and hosted by grunt gallery, an artist run center known for holding space for both Indigenous and LGBTQIA communities. The avant-garde performance was a semi-autobiographical enactment of her own journey to womanhood told through the first-person narration of an Indigenous woman, whose body was misinterpreted as a man’s by threatening colonizers. This performance, and Maracle’s larger artistic practice, challenged audiences by inviting them, not to accept and understand her gender identity, but instead to explore new ways to see and understand themselves by modeling transformation.

As a current conservative wave in the United States violently targets children and their access to gender affirming healthcare and social validation, the mobius strip helps us to recall that there are multiple ways of being and existing in the world. Gender has long been policed by colonial states, Canada, the United States, etc., through various laws, policies, and acts of violence. The enduring battle for gender sovereignty—politically, socially, and culturally—represents one of the most visceral and violent battles for abolition in the Americas. Often those on the front lines fighting for gender freedoms are the most vulnerable among us, rendered as simultaneously hyper-visible and invisible according to binary logics. Gender Mobius represents just one performance piece from Maracle’s dynamic forty-year career, but it remains exemplary of her bold use of performance art to assert her own gender sovereignty and selfhood, both on and beyond the stage.

Gender Mobius

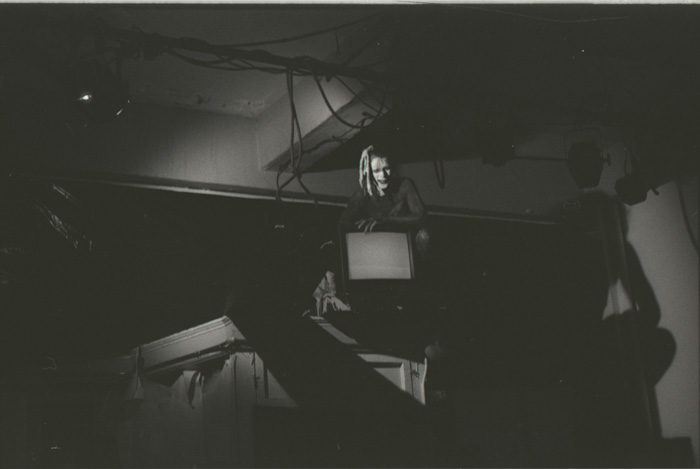

The performance begins with Maracle’s own mythologized arrival of Columbus to the Americas. The minimalist stage is decorated with crawling vines, flashing tube televisions, and scattered ceremonial objects. Maracle, dressed in flowing skins and a fur headdress, descends from a ladder onto the stage floor. She is alone, wandering the length of the stage beating a hand drum and chanting, a brief moment before European contact. The sound of sea birds and waves fill the stage. She draws out a long narrow strip of black paper that she then joins together to form the mobius strip. She displays the loop before the audience, breaking the performance convention of the fourth wall by establishing a relationship with the viewer. She jumps suddenly, as if startled by a sound from off stage, quickly stowing the strip away. Kneeling with her back to the audience, Maracle calls out, “Columbus?” which triggers a large projection to illuminate, displaying film footage of jovial white men on a wooden ship, celebrating after having spotted American land.

A colonizer, portrayed by a female Indigenous actor, swaggers across stage shouting, “Fucking queers!” The colonizer spots Maracle, “Indian too innit? Pagan savages, animals, heathens!” he shouts. He approaches Maracle, crowding her into a corner of the stage and knocks her on her back. He proceeds to shout out to the audience, again the fourth wall is permeable, “they don’t even have the sense to know there is only man and woman, man and woman, man and woman…” Pulling up Maracle’s skirt, the colonizer uncovers Maracles’ genitalia and pushes her away. “They tried to tell us they were special, had healing and seeing powers! That God was a she/ he and they was like them,” he says to the audience while gesturing at Maracle. He then pulls out his sword, “No, no, no, we can’t have that.”

Maracle depicts the point of contact with European colonizers as a literal and metaphorical rape. The audience becomes witness to the act, watching as she is physically and metaphorically assaulted. The dramatics and tone of the performance share similar camp affect with traditional Christian church plays. Gender Mobius is didactic and interactive. The audience would quickly sense that there was some moral lesson to explore as they are told Maracle’s story through physical performance and monologue. The race and gender-blind casting of the colonizers is intentional. At times absurd and humorous, the destabilizing of gender is blatantly displayed and vocally stated. As she moves across the stage, Maracle’s slender body is always centered, acting as an undulating focal point for both stage light and action.

The relationship between the colonial state and Maracle’s body is made palpable through her practice of performance art, especially in Gender Mobius where she intentionally presents her body to be consumed by others. It is through the senses of the body that we communicate and feel pain. Although the concept of gender sovereignty insinuates Maracle’s potential to express full agency and autonomy over her body and public presentation, it does not deny or escape the reality of her extreme vulnerability. Just as a nation’s sovereignty is negotiated through its relationships with the colonial state, Maracle’s gender sovereignty is negotiated through her relationships with other bodies that hold varying powers and privileges. Just as the nation could be conquered so can the body.

Maracle faced various forms of violence throughout her life that attempted to force her assimilation or destroy her. In the performance, she tells the audience, gathering herself in the aftermath of physical violence, to then describe how at a very young age, gender was weaponized against her to disconnect her from her tribal culture and spiritual sense of self.

Maracle emerges from a dark stage, no longer dressed in skins. Her bare body is revealed to be covered in black traditional Mohawk war paint. Her face is painted white, her lips black. She then begins her monologue,“I look into my past and hear my grandmothers whisper to me, down through history, rooted in the culture, for us to be who we were, to view the world, to have choice, choice was sacred,” she says. Maracle insinuates that oral tradition preserved Indigenous ways of living across generations. She paces the stage, passing in and out of the light. A drum plays off stage. She is taught to love her physical anatomy while embracing her woman spirit from her grandmothers. “Before they were allowed to be, beyond male and female, we could transform ourselves to become who we are, and in this the choice belongs to us.”

Maracle recalls entering school, an institution of the colonial state, where she encounters the gender binary. This culture shock reduces Maracle from her expansive, gender fluid self, to a hunched and self-loathing boy. She speaks of living as a man and being confronted with white men’s fear and sexualization of her Indigenous body. Inner community opposition to her true self also beat her down, “you’re crazy, we don’t want to hear that shit!” Then as she approaches the age of forty she heard the whispering of her grandmothers, they taught her how to heal the sickness of spirit. Upon her grandmother’s death, she accepted herself and her unique view of the world. By this point Maracle had climbed to a high point on the stage, revealing her body in full light to the audience as a warrior.

In publicly identifying as a “sovereign Haudenosaunee woman,” Maracle actively asserted her sovereignty against the definitions imposed by others, which implicated both her tribe and her gender. Maracle appears on stage in skins, face painted in traditional Mohawk fashion, simultaneously performing both gender and ethnic identities regardless of her geographical location. Haudenosaunee is a confederacy of six Indigenous nations that span the Northeastern portion of North America. Maracle was born on Six Nations reservation land near southern Ontario. When she was a one-year-old, Maracle and her family were removed from the reservation due to the enforcement of blood quantum laws, which determine one’s status as indigenous through fractions of one’s ancestry. A Canadian government agent determined that her father was not an “Indian” because his name did not appear on the official Six Nations’ register.3 Regardless of her father’s Haudenosaunee ancestry, his official claim to his Indian identity was in the hands of the Canadian government. Blood quantum laws, an extension of the colonial state’s power, define who is Indigenous and who is not, and thus, who has access to resources and who does not. The laws intrusively police intimate family structures that force Indigenous peoples to conform to the colonial state’s definitions of family, as well as marriage, gender, sexuality, and ultimately tribal identity.

Such efforts to police Indigenous identity are intimately tied with efforts to reduce gender identity to biological sex. Maracle was born a biological male but asserted her spiritual identity as a woman. Though she did not internally identify as “male,” Maracle lived the first portion of her life publicly as a “man,” engaged in marriage, and had children. At the age of forty, Maracle fully “transformed” into the woman she knew herself to be. This transformation was the result of years of internal work to decolonize her conceptions of gender so that her “Indigenous sense of gender” could be reclaimed. This sense of gender drew on ancient Mohawk understandings of spirit to honor those that were “female/male, yet were neither, nor both, but outside of, or beyond.”4 In other words, one’s spirit, rather than their anatomy, determines gender; sexuality is not determined by gender; and binary constructs of gender cannot contain the spirit.

For Maracle, the defining characteristic of ancient Indigenous gender construction is one’s ability to choose. Choice is sacred because it represents freedom in all matters relating to an individual’s being. Sovereignty is agency over one’s self, and gender expression is something to be discovered and enacted. Maracle refers to gender difference as “a gift from the ancestors” that is brought about through conscious understanding at birth, revelation over the course of one’s life, or spiritual visions.5 This construct of gender has an elastic quality that accounts for the inevitability of an individual’s growth and change over time. Through performances like Gender Mobius, she models the potential of living as her fully transformed self both publicly and on a hyper-visible platform. On stage, Maracle is simultaneously an actor and Aiyyana. The artistic choice to consistently break the fourth wall is to the benefit of those in the audience. Her ability to freely traverse realities is intended to help those unable to see or understand that systemic restriction of gender freedom is, in actuality, a larger threat to freedom in general.

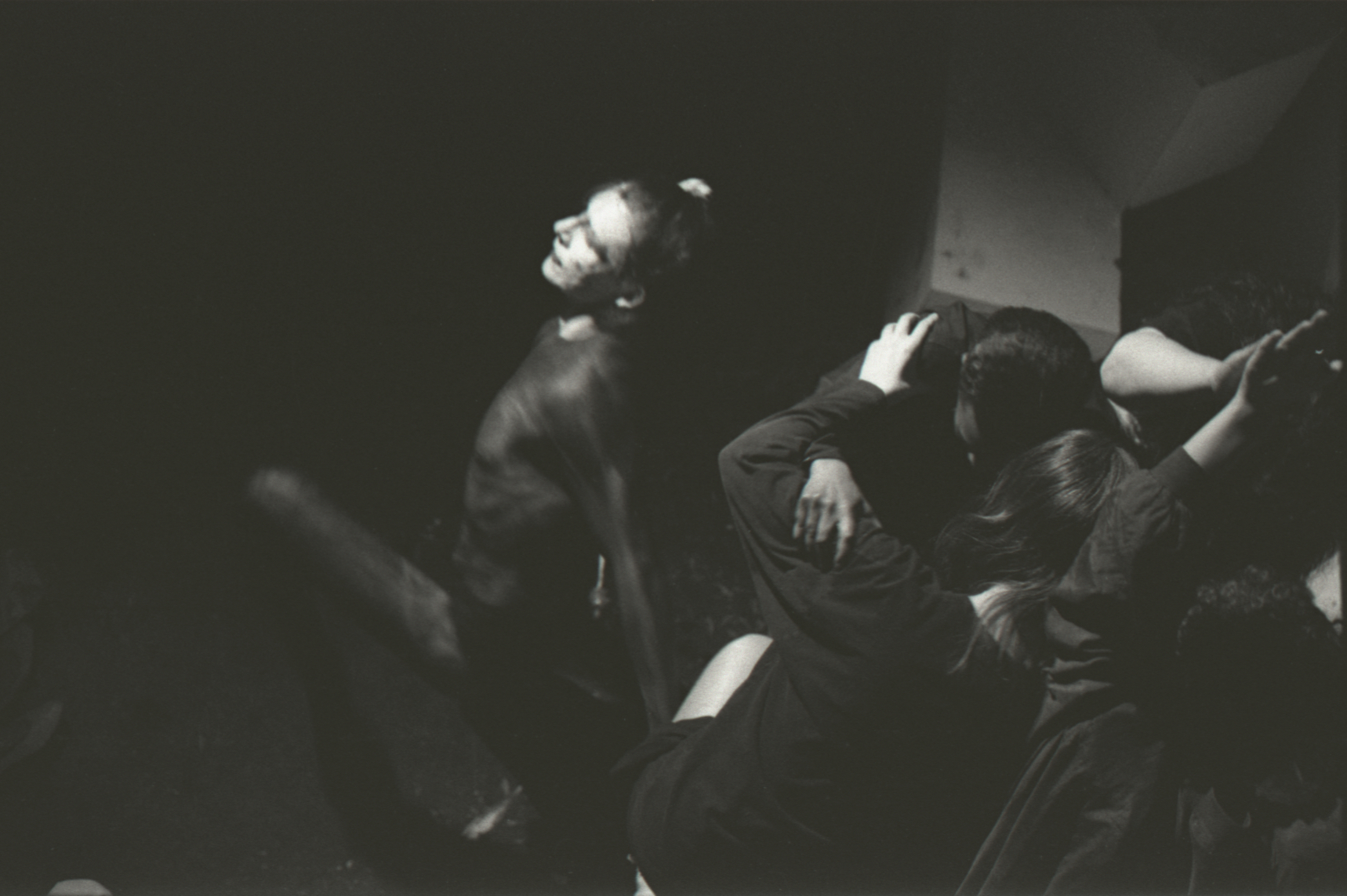

Perched high on a ledge above the audience, Maracle crouches before a hanging noose. Descending and ascending are strewn throughout the performance. This cyclical movement references the Haudenosaunee creation story of Sky Woman, where Maracle’s surrogate body falls to the Earth to birth a new world, transformed from her former self, leaving behind her former world. The music steadily progresses. “Not just woman, not just man. Something much beyond” she calls out. Reflecting on the power of her grandmothers, she shows reverence to them for, “that final bit of courage, to simply be.” She jumps and is swallowed by the darkness of the stage below. Performers then gather on stage and use their limbs to create a large vaginal portal from which Maracle reemerges. She calls out, “I am back, me, free.”

Performance as Monument

Contemporary discourses on the United States monument landscape continues to contend with the intersecting erasures of histories, cultures, and knowledges, all while imagining the potential to expand beyond patriarchal and white supremacist narratives. The most literal solution to addressing these erasures—and often the least impactful—has been to appropriate the physical body of a historical figure and render them in metal or stone so that viewing publics might recall their historical or cultural significance. However, what often makes a person historically significant has less to do with their physical appearance and much more to do with their actions. To those on the front lines of the battle for gender freedom, the permanence of a physical monument may seem hypocritical and inauthentic.

Historically, queer acts of resistance have often been performative—powerful, public gestures toward something beyond convention. If we understand gender as a performance, it is not farfetched to assume that the performance of gender through experimental art can be a transformative tool for society. Gender itself is not natural—it is a performative phenomenon that has become naturalized over time as subjects repeatedly perform regulated activities, and thus produce the illusion of natural sex categories. Judith Butler argues that “perfect” gender performance does not exist, so the chance to displace and transform gender exists for all performers.6 Gender expression is instilled in an individual through imitation and repetition. By performing gender outside of heteronormative binaries set by the colonial state, the body becomes a site of gender transcendence, offering a gender reality full of possibility.

Maracle understood gender as cyclical, as a mobius, because there are no fixed points; the endless possibilities of the mobius loop transcend space and time. Moreover, her non-static performance of gender sovereignty also offers a lens for understanding and expressing Native identities and cultures as continuous and expansive. By modeling multiple ways of being—being Indigenous, being a woman, being a grandmother—Maracle presented her body as a living archetype of decolonial gender sovereignty to her audiences. Finally, Maracle and several queer artists have used performance to remind us that it is not the brick that matters, but the gall to throw it. In seeking to publicly honor those individuals who are “female/male, yet were neither, nor both, but outside of, or beyond,” to honor those who fight in the battle for our gender freedom, past and present, it’s time we build them a stage.