Mark Krasovic is Associate Professor of American Studies and History, and Associate Director of the Clement A. Price Institute on Ethnicity, Culture, and the Modern Experience at Rutgers University-Newark.

It’s hard to say what Newarkers thought about the new monument being planned for their largest downtown park. They hadn’t been consulted on its theme, design, or location, and many of them likely learned of it from newspaper stories that ran only days before the agreement with a sculptor was formally executed. The monument to America’s soldiers and sailors was the third bequeathed to the city by Amos Van Horn, Civil War veteran and local furniture magnate whose lucrative empire was headquartered at his store on Market Street, on the block between High and Washington. Two of Van Horn’s monument commissions had already been completed, by the time the third — what would become Wars of America — was won by Gutzon Borglum in 1921.

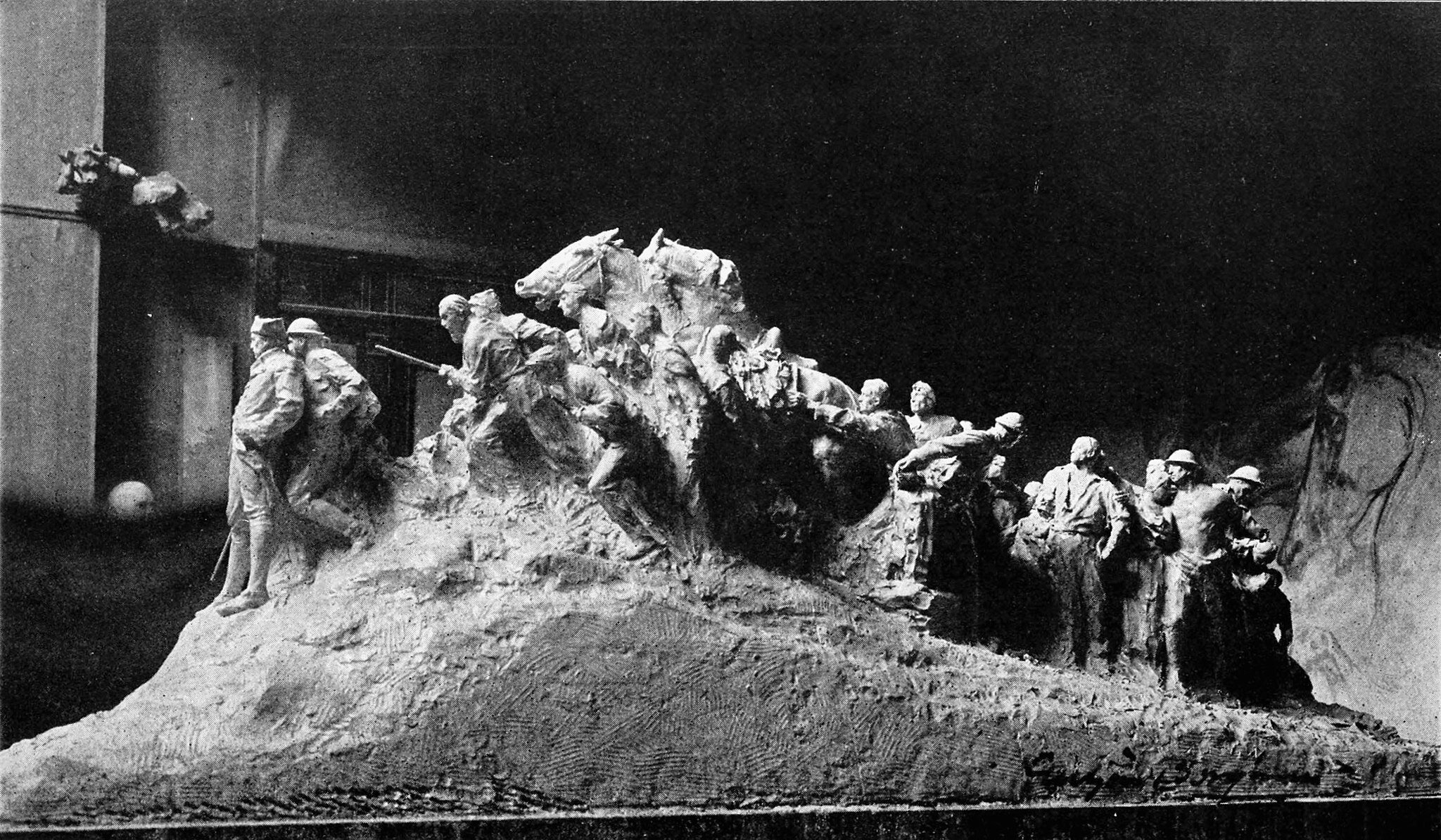

The son of Danish immigrants, Borglum was born in the Idaho Territory in 1867 and spent most of his youth moving about the Plains and Midwest before completing college, marrying his first wife, and traveling through Europe for much of the 1890s. There, he became familiar with the emerging sculptural modernism of his friend Auguste Rodin, and when he returned to the United States, settling in New York City, he would later serve on the planning committee for the 1913 Armory Show. His work came to eschew classical forms and allegory and embrace a quotidian humanism closer to the Ashcan School than the City Beautiful Movement. In 1911, in fact, he had completed Van Horn’s first commission: a seated, slightly slouched Abraham Lincoln situated on a small plaza before the white columns of the county courthouse. He later wrote to Ralph Lum, executor of the Van Horn estate, that his work was successful only “because I have freely developed the true human condition without camouflage…or chilling symbolism.” The third and final commission, then, would not be a laurel-wreathed celebration of military victory, but a study of “how humanity abandons its peaceful, legitimate life and risks life and takes life, that home and country may continue.” He completed a scale model — comprised of 42 figures and two horses — in late 1920, the Newark Evening News announced it as the winning design on February 11, 1921, and the official agreement was signed three days later.

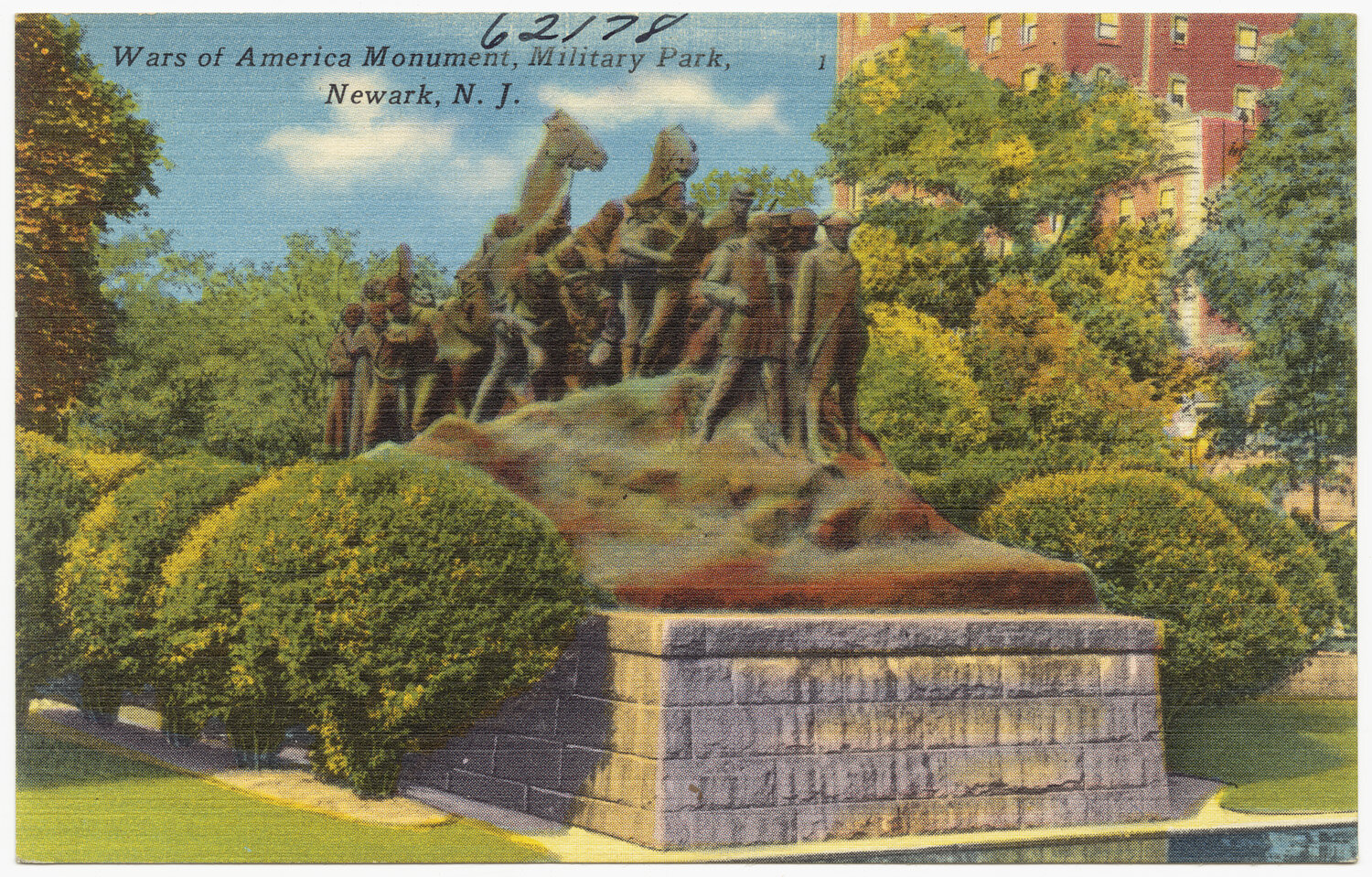

Wars of America Monument, Military Park, Newark, New Jersey, 1930 - 1945. (Boston Public Library via Flickr)

If Borglum’s thought and work increasingly embraced a key aesthetic convention of modernism, so too did they come to join a darker stream of modernity: the mainstreaming of scientific racism. In the years between the release of The Birth of a Nation and the restrictive legislative decrees of the 1924 Immigration Act, Borglum not only designed his Newark war memorial, but also began work on an even larger commission: a monument to the Confederacy at Stone Mountain, Georgia. The artist who had humanized Lincoln for the Newark masses and who had even named his son Lincoln, agreed to sculpt a colossal mountainside tribute to white supremacy and secession. Though it’s unclear whether he was ever a card-carrying member of the Ku Klux Klan, Borglum very clearly aligned himself with its cause and hobnobbed with its highest echelons, including Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans and the Grand Dragon of the Klan’s largest regional branch, D.C. Stephenson, with whom he composed a massive body of correspondence. In one letter, Borglum explained that he hoped his monument would expunge the word “rebel” from the Confederacy, since he believed they fought for core American principles. In other letters, he wrote of the “treachery” of “negro delegates” at political conventions, proposals for the federal government to break up and Americanize “colonies of Poles, Hungarians, Italians,” and of “alien-manned city industries,” “Nordic blood,” and “mongrel hoards.”. (None of this, however, stopped him from insisting his work be finally cast in bronze by Italian workmen in Firenze, Italy, or employing a young Isamu Noguchi as an apprentice on the project.) And so, in a downtown park, a public gathering space for all Newarkers, on dispossessed Lenape land, now stands the work of a preeminent American artist who once wrote to his friend the Grand Dragon that “involuntary union produced a mongrel hybrid product, resulting in general degeneracy toward the lower race.”

Military Park, Birds eye view of Military Park facing north from above Raymond Blvd., April 2008. (Wikipedia)

When we think about what a timely monument for Newark would be today, it might be worth considering Borglum’s contradictions a century ago as emblematic of broader dynamics in a city that was home to brave nineteenth-century abolitionists and to opponents who burned Lincoln in effigy; that absorbed waves of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe just before it celebrated its 250th birthday by highlighting its Puritan “founding”; and that has since become home to new waves of migrants, both domestic and international, and also to racial violence, police brutality, and an immigrant detention center.