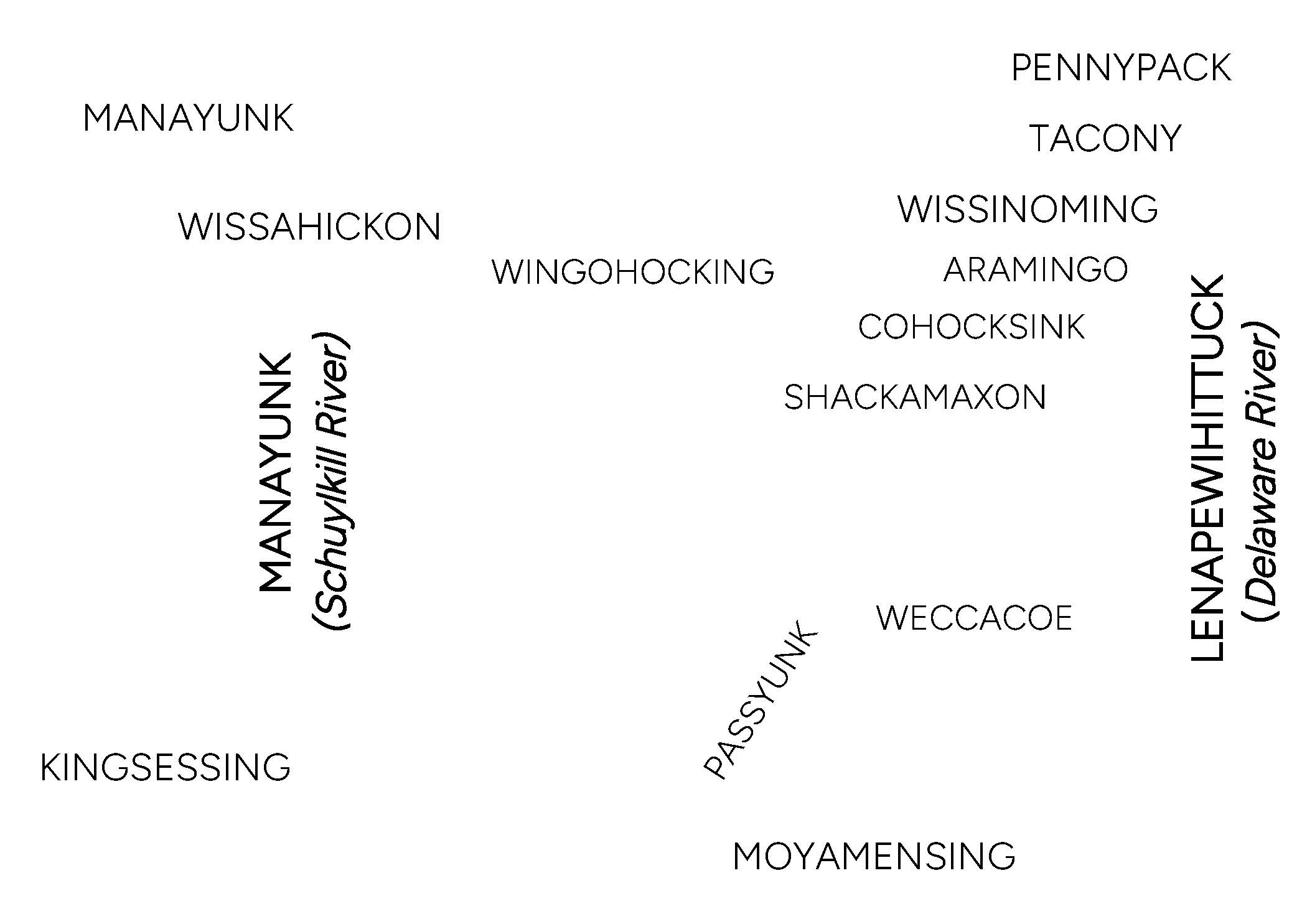

Aramingo, Cohocksink, Kingsessing, Manayunk, Moyamesing, Passyunk, Pennypeck, Shackamaxon, Tacony, Weccacoe, Wingohocking, Wissinoming, Wissahickon—these and other Lenape place-names mark the map of present-day Philadelphia.

Each name is a legacy that connects Lenape descendants to their ancestral homeland. Thanks to land acknowledgments, many Philadelphians now recognize the Indigenous name of this homeland as Lenapehoking (an Anglicized version of Lënapehòkink, or “the land of the Lenape”), encompassing parts of eastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey, southern New York, and Connecticut.1 Far fewer Philly residents know the historic Lenape name for the land upon which the city stands: Coaquannock (from cuwequenáku, “the grove of long pine trees”).2

The names Coaquannock and Philadelphia represent larger themes in the United States. All place-names (toponyms) carry memories of place, but on the settler-colonial landscape, names tend to encode mistranslations, miscommunications, and distortions. Many settler toponyms, which function as spoken claims of ownership, reflect histories of dispossession and deceit. Imperial powers have displaced, altered, or erased countless Native names by inscribing “new” origin stories upon Indigenous landscapes that, in the words of Paul Carter, “already answered to a cultural history.”3

Despite growing movements to recover Indigenous geographies through land acknowledgements and digital mapping projects,4 many non-Natives remain unaware of the depth of Native histories where they live, and the complexities of colonial erasures that have obscured these pasts as out of reach, seemingly situated someplace else. This is especially so in Pennsylvania, where, due to histories of relocation, there are no resident federally-recognized or state-recognized Indigenous nations. In the absence of Native presence, the meanings contained by place-names—both settler and Indigenous—are decontextualized, representing histories severed more than memories preserved. The conscious linking of Coaquannock and Philadelphia reminds us that Native and settler understandings of place are entangled in the same landscape.

The increasingly common custom of Indigenous land acknowledgment—written or spoken displays of respect in public settings—aims to decolonize settler space by emphasizing the enduring presence of Native places, in situ. To extend this tradition, we can move not only to recover Indigenous histories of place, but to also confront the distortions of colonial placemaking head-on. One path forward is to critically examine discrete landscapes of settler and Native toponyms as monuments: geo-temporal markers that carry historical meaning. Like material monuments, place-names can be invented, co-opted, recognized, contested, erased, or transformed. When they appear on official signs and maps, place-names are “statements of power and presence in public.” But when they appear on the lips of speakers as literal statements, place-names carry subtle, distributed power. Only by listening—historicizing, defining, and contextualizing place-names—can we fully hear their presence.

Lenape Names

Indigenous peoples have lived in the mid-Atlantic region for more than 10,000 years.5 Archaeologists working in and around Philadelphia have found that many historic Native sites show signs of consistent re-occupation, often seasonally, and sometimes over the course of centuries.6 Linguists have identified two different but related dialects of the Lenape, or Delaware, language in the broader Algonquian language family: Munsee, historically spoken in the upper Delaware River Valley and lower New York State; and Unami, spoken in the middle and lower Delaware River Valley, including eastern Pennsylvania and southern New Jersey.7

The seventeenth-century Native inhabitants of Lenapehoking used no specific word to identify themselves other than Lenape, meaning “person” in the Unami dialect, yet this name seldom appears in historic documents.8 More commonly, Native individuals and groups self-identified “as a people from a particular place or a certain river.”9 For example, in the early 1700s, some Lenape people began to identify as Delaware, a loan word adapted from the name of the colonial governor Thomas West, Baron de la Warr (c.1576–1618); this term also became the English name for the Delaware River.10 Munsee, a name from the northern part of Lenapehoking, was used after 1727 by exiles forced from their ancestral homelands in today’s Northern New Jersey.11 Today, Lenape descendant nations—who identify as Delaware, Munsee, and/or Lenape—live in places as disparate as Oklahoma, Kansas, Wisconsin, Ontario, and New Jersey.12 Curtis Zunigha (Lenape/Delaware), Cultural Director for the Delaware Tribe of Indians in Oklahoma and Co-Director of the Lenape Center in Manhattan, describes the Lenapewihittuck “river of the Lenape” (today’s Delaware River) as his ancestor’s archive.13 Lenape place-names can be found up and down the Lenapewihittuck, from the Munsee name Minisink in New York (from munusung, meaning “at the island or place of islands”) to the Unami Cohansey (from gohansik, “that which is taken out”) in southern New Jersey.14

The majority of Lenape toponyms can be considered locative terms, “descriptive” or “geographic nomenclature” that describes specific topographical features.15 For example, Neshaminy (in today’s Bucks County, Pennsylvania) likely stems from neshamhanne, “two streams making one.” Nesquehoning (in Carbon and Schuylkill counties) likely stems from næskahónink, “at the black lick,” from the root word næskahóni, “black lick or the lick of which the water is of a blackish color.”16 Other Lenape place naming practices follow what Thomas Thornton calls “geographical psychology”; these names refer to practical uses of a given location, such as places to procure food or other resources.17 For example, the toponyms Perkasie (Berks and Bucks County, Pennsylvania) derives from the Northern Unami pilgussink, (meaning “place of peaches”), while Aquashicola (Carbon and Monroe Counties, Pennsylvania) derives from achquaonschícola, ("the brush-net fishing creek; the creek where we catch fish by means of a net made with brush”).18

In Philadelphia, Lenape names and their Anglicized approximations include Manayunk (from mëneyung, “place to drink,” the Lenape name for the Schuylkill River); Passyunk (from pahsayung, “in the valley”); Pennypack (from pënëpèkw, “where the water flows downward”); Tacony (from tèkhane, “cold river” or tèkene,“woods or forest”); Wissahickon (from wisamêkhan, “catfish creek” or wiiawhìtkunk, “place of yellow trees”), and many others.19 Some Lenape toponyms—such as Cohocksink (“pine grove”), Wingohocking (“choice land for planting or cultivating”), and Wissinoming (“where we were frightened, put to flight”) representing the names of now-buried creeks—have since been borrowed to designate nearby street signs, parks, and community centers.20

The prevalence of Lenape names on the contemporary map represents deep and enduring worlds of meaning, despite colonial erasures. What is now called Philadelphia has been and continues to be an important Native place—for historic Lenape people and their descendants, and for other Indigenous communities forged through histories of dispossession.

Settler Names

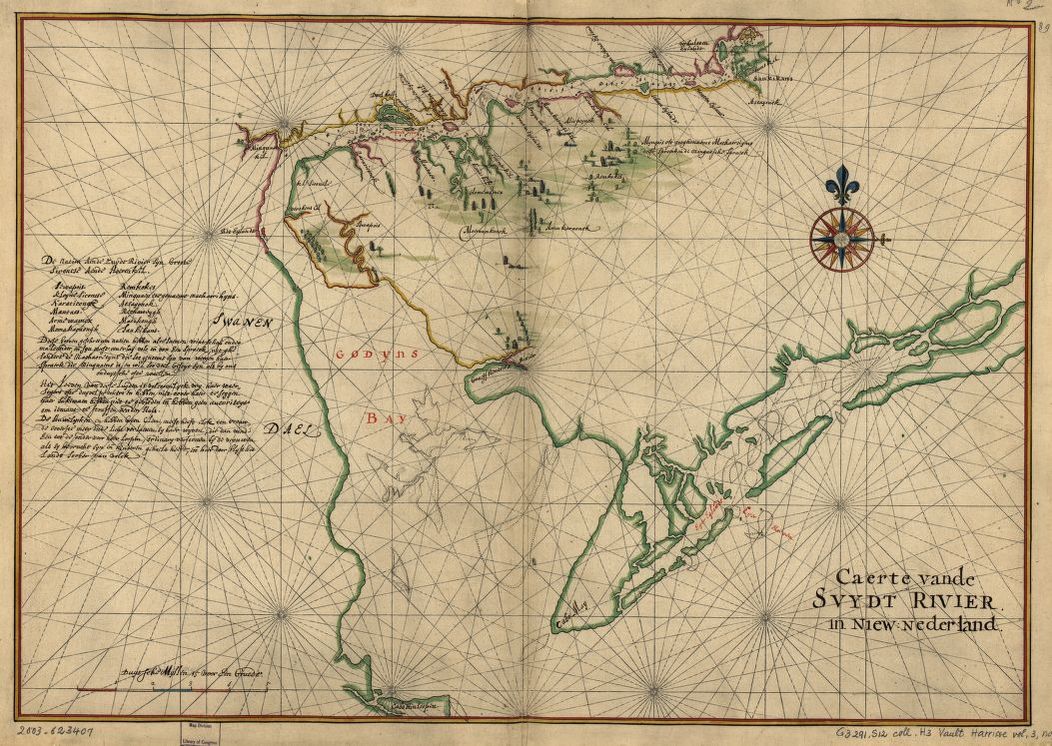

The first colonists to lay claim to this area arrived with the Dutch West India Company, which claimed parts of present-day eastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York, including the lands that would become Philadelphia, as part of “New Netherland.” The Company, holding quasi-governmental power, substantiated their claim based on Henry Hudson’s (c.1565–c.1611) 1609 voyage of “discovery” and Hugo Grotius’s (1583–1645) legal scholarship, which was sponsored by Dutch East India Company.21 In A Description of New Netherland, published in the Dutch Republic in 1655, New Netherland lawyer Adriaen van der Donck (1620–1655), compared the “Zuid Rivier” (South River, today’s Delaware River) “to the superb Amazon River not so much for its size as for the other outstanding qualities,” including its “rich, fertile fields… well suited for establishing sizable settlements, villages, and towns.”22 Yet, in his (seemingly) encyclopedic text, he provided no specific reference to the many Lenape towns that had lined the Delaware River for generations. Van der Donck’s account minimized the presence of Lenape people while simultaneously appropriating Lenape homelands as part of a Dutch possession.

Subsequent histories of Pennsylvania, and especially Philadelphia, revolve around the English Quaker colonist William Penn (1644–1718), who colonized and named both places. In 1681, with a royal charter granted by English King Charles II (1630–1685), Penn set out to purchase discrete tracts of land from Lenape sakimas (chiefs). Penn admired the sound and structure of the Lenape language, writing in a letter to the Free Society of Traders in 1683: “I know not a language spoken in Europe that hath words of more sweetness or greatness, in accent and emphasis, than theirs…”23 However, legally and rhetorically, he envisioned Pennsylvania as his possession—the name literally translates to “Penn’s Woods.” The city’s name, Philadelphia, was borrowed from an ancient city of the same name, located near present-day Alaşehir, Turkey, founded by the King of Pergamon, whose name was Attalus II Philadelphus (meaning “Attalus the brother-loving”) (159–138 B.C.).24 William Penn most likely came across the name Philadelphia while reading the Bible, since this place-

name is referenced in the Book of Revelations as one of the seven churches of Asia.25

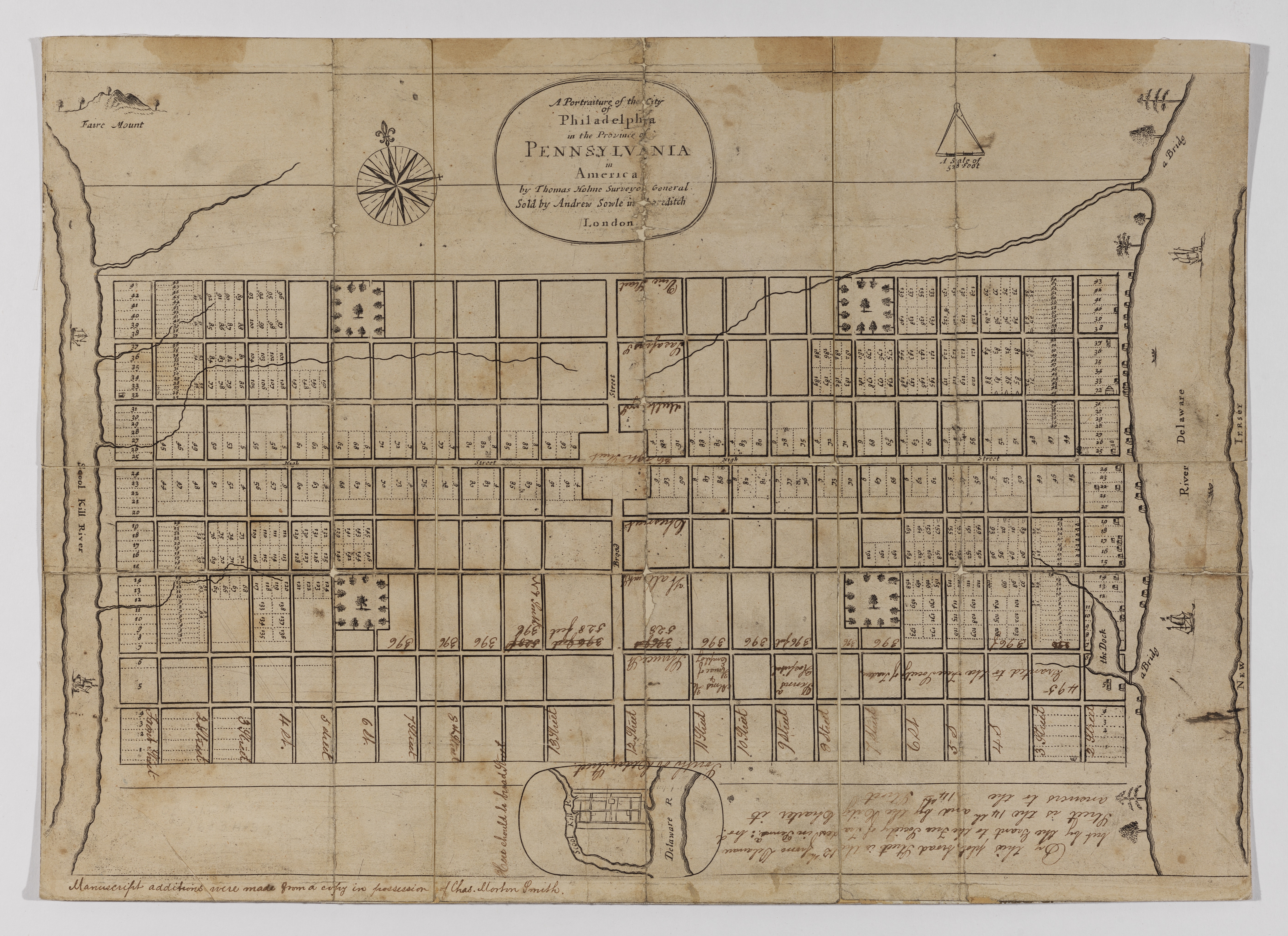

The English Surveyor Thomas Holme (1624–1695) first depicted Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in a map published in London in 1683. This aspirational portrait of the “newly laid out” city (which was neither built nor inhabited at that time) circulated in England alongside a nine-page “Letter from William Penn, Proprietary and Governor of Pennsylvania” and a one-page “Short Advertisement” about the plots for sale. In his letter, Penn declared:

For the good Providence of God, that of all the many Places I have seen in the World, I remember not one better seated; so that it seems to me to have been appointed for a Town, whether we regard the rivers, or the conveniency of the coves, docks, springs, the loftiness and soundness of the land and the air…26

Carefully plotted and worded, these advertisements not only encouraged the physical colonization of Lenape lands, but also shaped a sense of colonial order that still persists into the present. Holme’s map situates the largely blank grid of the city between two rivers: the Delaware and the “School kill.” The first is a reference to Lord Delaware, an early English colonial governor of Virginia; the second is an English approximation of a Dutch toponym. The name Schuylkill means “hidden river” in seventeenth-century Dutch; the suffix -kill (“creek or stream”) appears regionally in varied forms, such as the Catskill Mountains and Arthur Kill in New York, and Paulins Kill in New Jersey.

Investors, surveyors, promotors, commissioners—these classes of colonizers told new stories about Native places. Like the Dutch colonists who preceded him, Penn understood that Lenape people claimed rights to their lands, and he suggested as much in the treaties he signed. But all of these colonial cultures and governments claimed Lenape lands before they (un)settled them, describing large swathes of this landscape by name and by law as their “possession.” When we consider Penn’s legacy, we should think first about the name eighteenth-century Lenape peoples living in Bethlehem remembered him by: “Miquon” (literally, translating to “Quill” or “Feather”), a tool of signing.27

Enduring Names

Settler place-names are, in effect, origin stories that flatten Native worlds of meaning. Yet, on a continent with tens of thousands of years of Indigenous histories, Native names are impossible to entirely erase. Even contemporaneous colonial maps and private correspondence contradict the distortions of public-facing promotional accounts. For instance, a 1639 map and legend published by the Dutch cartographer Joan Vinckeboons (1616–1670) highlights several Lenape “nations on the South River” (Natien aende Zuydt Rivier), including the districts of Armewanex (Armewamus), Sankikans (Sanhican), and Matikongh, located near today’s Camden, Trenton, Bordentown, respectively.28

Looking cautiously at the extant documentary record, it is possible to recover some traces that reflect how historic Lenape people thought about these places. In private letters exchanged between Dutch West India Company officials through the 1600s, it is clear that Lenape leaders on the ground restricted colonial claims that appeared limitless in published works like van der Donck’s. According to a 1648 report by Andries Hudde to Director-General Peter Stuyvesant (c. 1612–1672), unnamed Lenape sakimas from Passajonck (the village from which Passyunk derives its name) said it:

. . .amazed them that they (the Swedes) wanted to prescribe the law to them, the native owners, so that they would not be able to do with their own possessions whatever they wanted; that they (the Swedes) had only recently come into the river and had already seized and occupied so much of their land.29

While criticizing the Swedes, the “principal chiefs” Mattehooren and Wissemenetto nonetheless appear to have ordered the Dutch officer to build along the Schuylkill. Hudde wrote: they “themselves planted the prince's flag there and ordered me to fire three shots as a sign of possession” before he began to build under their watch.30

Later Lenape leaders also criticized English colonists for their land-grabbing tactics, especially in the aftermath of the fraudulent Walking Purchase (1737), perpetrated by James Logan (1674–1751) and William Penn’s sons John and Thomas.31 During a 1756 speech in Easton, Pennsylvania, the Lenape sakima Teedyuscung (1700–1763) declared to colonial governor William Denny: “this very ground that is under me was my land and inheritance, and it is taken from me by fraud.”32 Some of the earliest written references to Lenape place-names in the westernmost portion of their ancestral homeland come from legal complaints delivered by Lenape people to Pennsylvania’s colonial government. For instance, the first documentation of Mahoning in today’s Carbon County, Pennsylvania (from mahóni, “a deer lick,” and mahonink, “at the lick”) comes from a November 12, 1740 letter expressing Lenape beliefs that they were being wrongfully removed from lands that did not fall “within the limits of the Walking Purchase.”33

If we listen, the North American landscape speaks many voices at once. The sounds are slightly cacophonous, but they are far from random. Colonial place-names represent settler colonists’ attempts to re-inscribe Native places with new histories, often within discourses of possession. We unconsciously erase Lenape memory and speak in William Penn’s memory, however disjointed, whenever we voice his chosen toponyms. We uncritically replace the ancient river name of Manayunk with “Schuylkill”—a seventeenth-century Dutch name that speaks to a colonial vision partially realized. Though many signs of Dutch colonial history in this region have receded from view, “Schuylkill” is an enduring reminder that colonial forms of claiming and placemaking distort Native histories.

Settler names take up mental and physical space over Indigenous histories, but cannot entirely erase them. Here, as in many other locales, Native toponyms and their meanings are well documented and easily retrievable. On a recent visit to Boston, for example, a quick Google search presented me with the Algonquin name for what is now called the Charles River: Quinobequin (meaning “meandering”).34 In other cases, collaborative, interdisciplinary efforts are needed to piece together Native histories nearly lost and long underrecognized. When we interrogate place-names as monuments on the American landscape, we start to ask deeper questions that move beyond simple land acknowledgement: Who named this place, and when? What other names might exist for this place, and what are their political connotations? Which Indigenous nations still have an ancestral claim to this place? Is their sovereignty respected and supported at present? Are these nations advocating to have their land back? At bare minimum, not unlike the way Manhattan and New York have been interchangeably used since the seventeenth century, Philadelphians can recover Lenape histories of place by recognizing similar entanglements: Manayunk and Schuylkill; Philadelphia and Coaquannock; Pennsylvania and Lenapehoking.