Collective memory projects hinge on visions of the possible. Whether renegotiating meanings associated with existing representations of the past or aspiring to construct new commemorative objects, communities define monuments not as passive consumers of historical sites but rather by the claims they make on what is—and should be—recognized. In St. Louis, such commemorative campaigns have been defined as much by the absence of missing or displaced objects as by the statues and other markers visible in public space.

The shifting mnemonic terrain around the city’s Civil War history is a case in point. St. Louis’ status as the largest outpost in a border state with bitterly-divided Union and Confederate sympathies had long been prominently represented by two objects: a statue of Union Brigadier-General Nathaniel Lyon in a heavily-trafficked Midtown thoroughfare just down the road from the city’s crown jewel Forest Park, where a 31-foot tall monument to the Confederacy also stood. Today, neither object remains in place—Lyon banished under the cover of darkness in 1959 to an isolated park in the city’s southern fringes, and the Confederate monument removed in 2017 following a prolonged battle over the object’s place within the city’s limits. Such reappraisals more recently echoed in St. Louis University’s failure, following objections from alumni and others, to follow through on its promise to establish a permanent “mutually-commissioned artwork” recognizing the Occupy SLU protests in the wake of the 2014 police killing of VonDerrit Myers, Jr.

In cases such as these, decisions to remove, reposition, or rescind the placement of monumental objects were far from transparent and precluded meaningful dialogue among stakeholders in the community. This backdrop underscores the power of possibility in Monument Lab’s work. By asking St. Louisans how they would map the city’s monuments, the Public Iconographies project offers an open and inclusive platform to re-envision both what is and what might be.

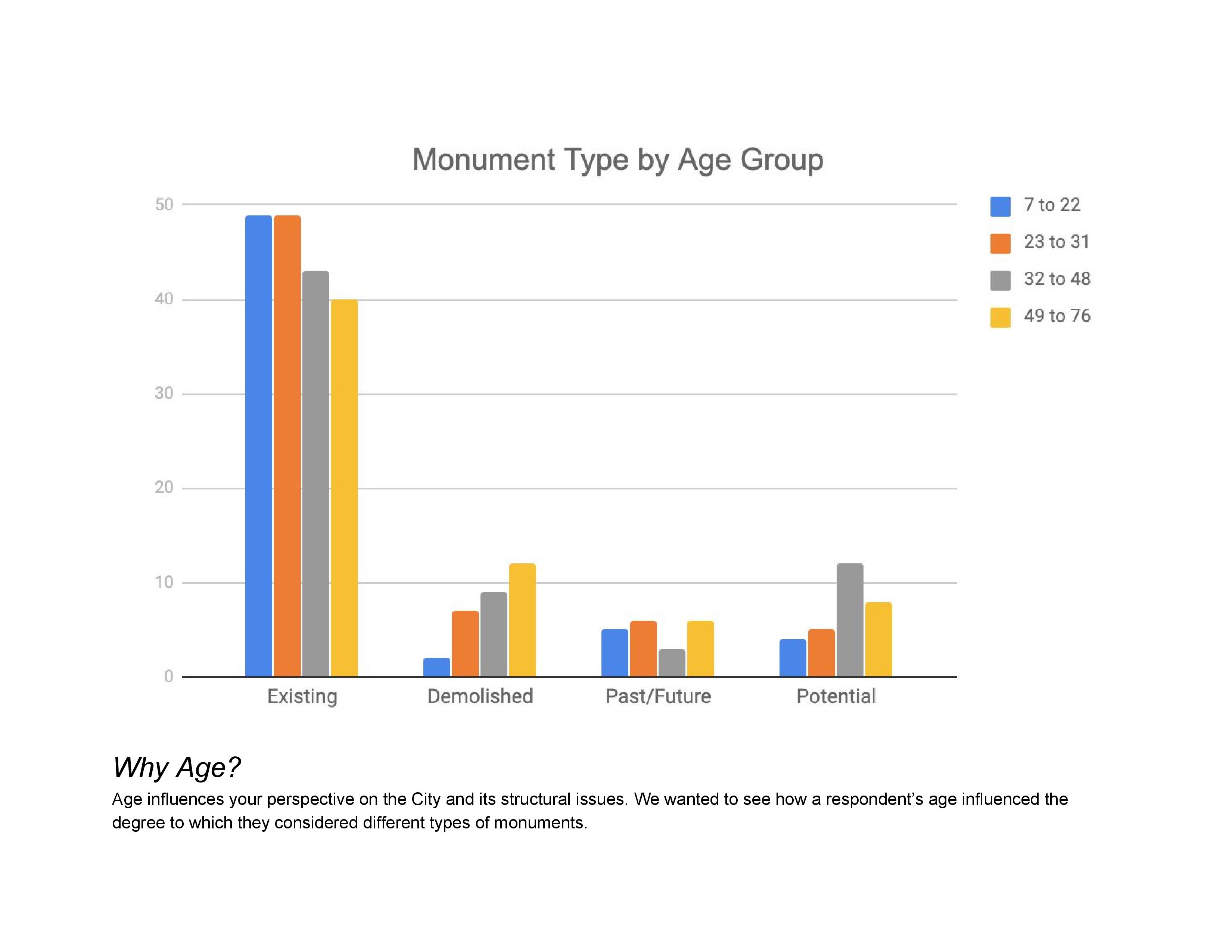

In late 2019, this crucial intervention became a core focus of the work of our Sociology seminar on Social Conflict at Washington University in St. Louis. Aiming to visualize the hundreds of public responses gathered by Monument Lab, the Public Iconographies research tem, and the Pulitzer Arts Foundation staff, we initiated our process by assigning each of our 29 students a subset of maps, focusing less on broader context and encouraging students to record their impressions about content on the fly. These reflections allowed us to consider key dimensions along which to organize and present as many representations as possible without clouding the viewers’ interpretive power. Utilizing a modified design-thinking approach, we ultimately settled on organizing an exhibit by differentiating the age of each map creator along with the emphasis in each map on monumental objects that were existing or demolished, versus potential or imaginary.

Next steps focused on setting the exhibit’s location, design, and content. Working on a large (29’ x 10’) wall in Washington University’s sociology department, students assessed the dimensions of the space, curated and organized the placement of specific monument maps, designed and interspersed sociological analyses throughout, and worked with the Pulitzer’s Kristin Fleischmann Brewer and Joshua Peder Stulen to visualize and carry out the installation. Throughout the process, the students reflected on their curatorial decisions as well as how those were expressed in the content of the exhibit.

What did we discover?

True to the project’s emphasis on reflecting on the significance of mapping absent elements alongside iconic and visible ones, we quickly realized that, given the available space, our process would necessarily require selecting some subset of maps for display. Students decided to focus on those maps whose authors had included information on their self-identities, but also emphasized constructing additional displays to incorporate other maps and potential audience voices as well. Those took the form of portable booklets, in the spirit of a fold-out map, along with a satellite exhibit that invited audience participation and displayed some maps that felt vital to our collective understanding of the project but did not fit into our group of identity-labelled maps.

Both the presence and absence of sites across the collected monument maps also informed our reflection on the exhibit’s content. Viewing our grouping of several hundred maps as a whole, one evident finding involved Washington University itself—in particular, the university’s relative invisibility in public imaginings of the city’s landscape. This lack of recognition reflects dual perceptions of the campus as both central player and perennial outsider in the city, and perhaps defines it as an elephantine site of possibility as the university strives to fulfill its newly-declared mission to be not only “in,” but also “for,” St. Louis.

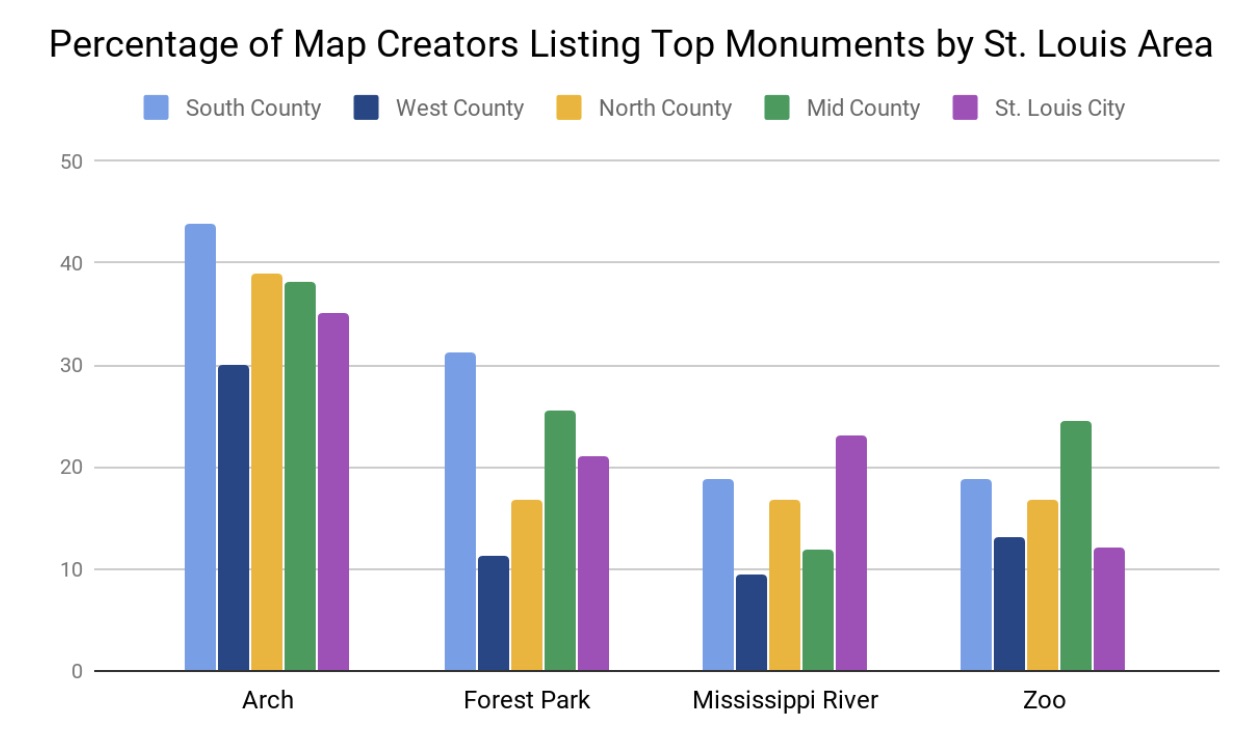

More generally, while the maps as a whole highlighted hundreds of commemorable sites, the most commonly-marked ones—the Gateway Arch, Forest Park, the Mississippi River, and the St. Louis Zoo—held true regardless of whether the map-creators resided in the city, or North, West, or South County. That said, location did reflect important differences among those sites, with North County residents significantly less likely to highlight Forest Park than other popular sites, and those residing in the city more attuned to the river and the least likely to emphasize attractions like the zoo that retained considerable salience among county residents.

Ultimately, the impact of Public Iconographies resides not in these broad patterns, but rather in the project’s ability to open a space in which individuals’ visions can be advanced and seen. Indeed, St. Louis’ future will be shaped by public understandings of its past, represented not only by the monumental landscape but also in aspirations around what we might—and should—claim as essential features of the city’s collective story.