In the United States, we have now surpassed the somber milestone of 500,000 people killed by COVID-19. This weight of an unfathomable collective grief burdens our best efforts at national recovery.

In the midst of an avalanche of catastrophic losses, our national death toll climbs to numbers surpassing some of the most costly and gruesome wars in memory. Each day brings with it a mass casualty event. As we struggle to wrap our heads around such horrific statistics, the trauma of this past year lingers in our bodies and our minds.

Our time-tested routines for mourning and commemorating loved ones and neighbors are beyond advisability for the protection of the living. Multiplied across families and social networks across the country, the impact of deferred funerals and delayed memorial services is immeasurable to quantify. Our shift to virtual shrines and shivas, though strained, highlight resilient forms of coping and duty-bound calls to remember.

While the work of imagining COVID-19 memorials is already underway, we must envision commemorative spaces to hold grief and accountability. In other words, resist the tempting habit of building memorials that tell single stories of heroism and closure without reckoning with our nation’s traumas, grief, and inequities.

We have certainly reached a new day in the fight against the pandemic, following nearly a year of federal indifference and antipathy under the previous administration. In 2020, we experienced a painful lack of officially-recognized national days of mourning. Even rare moments and expressions of grief were drowned out by the noise of disinformation and denial, blame and bigotry. It was not until the eve of the 2021 presidential inauguration that we shared a moment of national silence.

When we think of civic monuments and memorials, we generally understand them as places to mark the past and tender lessons for future generations. Too often, we leave stone and marble sites to speak for themselves, and as such shape official memorials that ultimately stunt historical awareness rather than open up spaces for future generations to continue writing its story.

The most moving of monumental sites – for example, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial and the National Peace and Justice Memorial – are never static. Such transcendent sites of memory are so effective because they invite viewers to take part in authoring and shaping a fuller story beyond their built structure. Refusing to close the loop on history, these memorials balance presence and absence, grief and resilience, and personal and collective forms of healing.

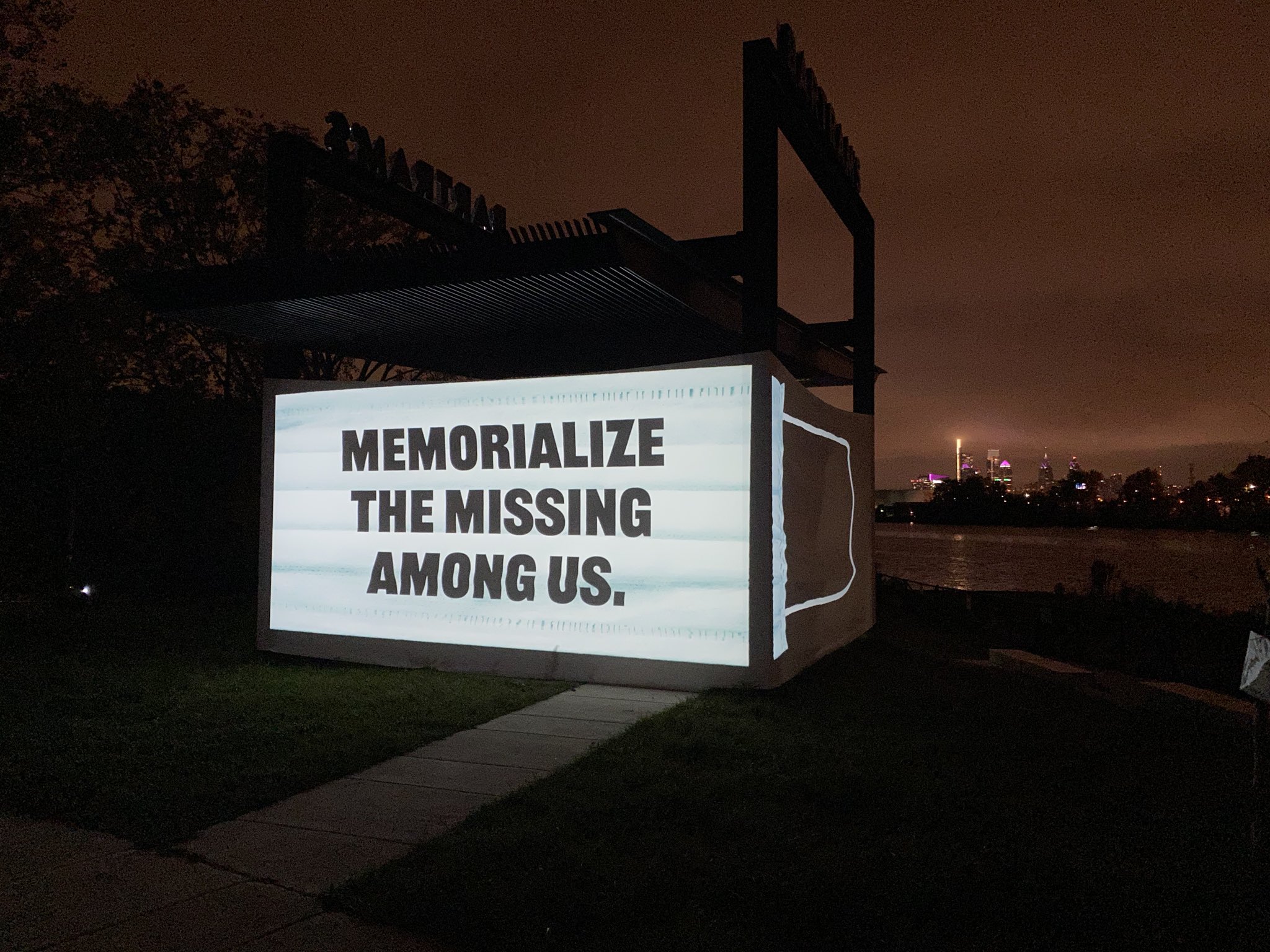

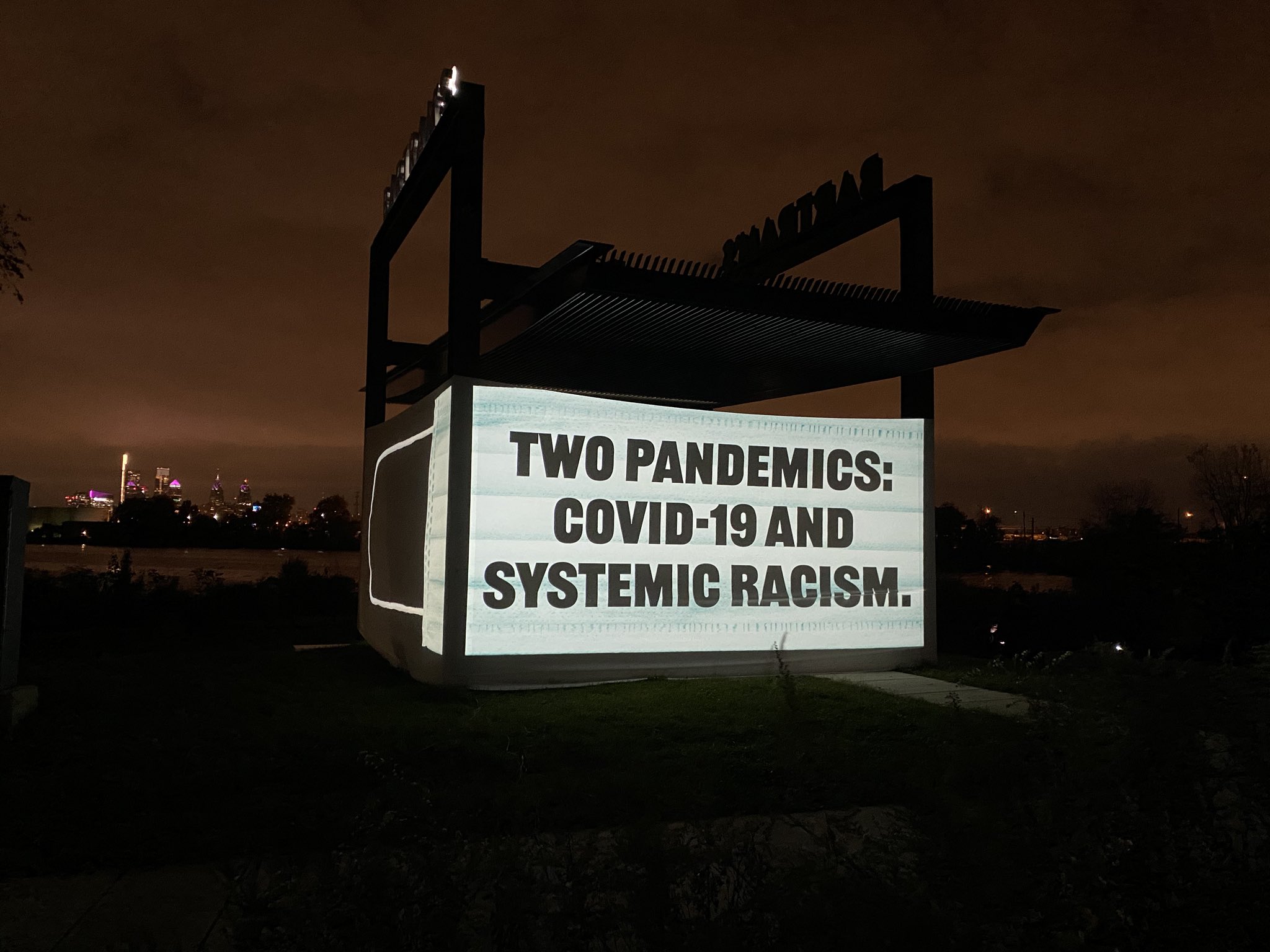

Other “temporary” interventions, including the historic AIDS Quilt on the National Mall and more recent anti-racist projections along Richmond’s Monument Avenue, rewrite grand narratives by layering communal visions in resistance to the status quo.

Together, such built commemorative sites and grassroots activations remind us that no monument is “permanent” in and of itself – they depend on maintenance, resources, and a collective will to keep them from crumbling.

Monuments are neither static nor inert. Their stories are continuously written by people through time, calling us to envision memory as collective, vital, and potentially reparative.

History has shown us that public health crises, especially pandemics, are largely absent from the conventional monument landscape. For example, the Flu pandemic of 1918 killed millions worldwide, including 675,000 Americans. But the Flu and its victims have largely vanished from collective memory and are almost fully absent from monumental representation. In contrast, there are hundreds of memorials to World War I, despite the fact that the virus nearly killed as many soldiers as did military combat.

This chasm in our nation’s public memory begs the questions for our current predicament: What are we willing to remember? Which narratives are elevated as part of our national story? The amnesia over the 1918 pandemic has proven to endanger us, demonstrating that fuller forms of remembrance should be part and parcel of democractic participation.

Surely, our COVID-19 memorials should commemorate those we have lost and forgotten, as well as grapple with the enormity of the death toll. Memorials could also serve as offerings of gratitude to first-responders, teachers, healthcare workers, parents and caretakers, sanitation and custodial staff, delivery workers, and others who continue to bear the burden to make it through.

But the COVID-19 pandemic has put other crises into relief, laying bare socioeconomic and racial disparities in mortality and healthcare, deep-seated anti-Asian racism, and the economic toll on women and their labor, among other alarming revelations.

American memorials to COVID-19 must recognize the intersections of systemic racism, social inequity, and a year lost to federal indifference. One such project is the A/P/A COVID Voices: A Public Memory Project, an archive of artifacts that highlight the overlapping contexts of the pandemic, systemic racism, and the transnational Black Lives Matter movement. Without incorporating these multiple experiences of the pandemic in future memorials, we will memorialize the pandemic in ways that lack in texture and truth. Our monuments and memorials should work toward justice.

If we memorialize without recognizing the weight of our losses and the forces that shape them, we risk a public memory that only superficially numbs our nation’s collective pain, undermining short- and long-term pathways to healing and recovery.

Otherwise, we will do disservice to ourselves and future generations seeking guidance from history and signposts for survival.