It has been a rich and rewarding experience working with Monument Lab, the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, and Washington University faculty and students around the Public Iconographies project and its monument mapping data. As a newcomer to St. Louis, I have learned much from this data and conversations about my adopted hometown, and the project has created unique research and teaching opportunities. I have worked with students in several classes to develop their own Monument Lab maps and analyze maps generated by others in St. Louis. In my Monumental Anti-Racism class, a seminar and practicum where we explore the racial politics of public memory and propose anti-racist commemorative interventions, we have drawn inspiration from Monument Lab and its partners, and used the map archive to probe the idea and practice of anti-racist memory work.

The collaboration has been generative in my related work on histories and legacies of racist violence, which played a significant role in my decision to make St. Louis home. Even more so than the relevant history of this wounded city, what drew me was the broader history of Missouri – freedom’s compromise state – and the larger Mississippi River valley, a vast catchment area for national and global histories of racist violence and exclusion, and their legacies today. Missouri’s statehood and soil literally rest on an agreement to reject democratic principles of freedom and equality in the furtherance of white racial dominance; ordeals of American Indians, African Americans, whites, and everyone else in the region have been shaped by the wake of this racist pact.

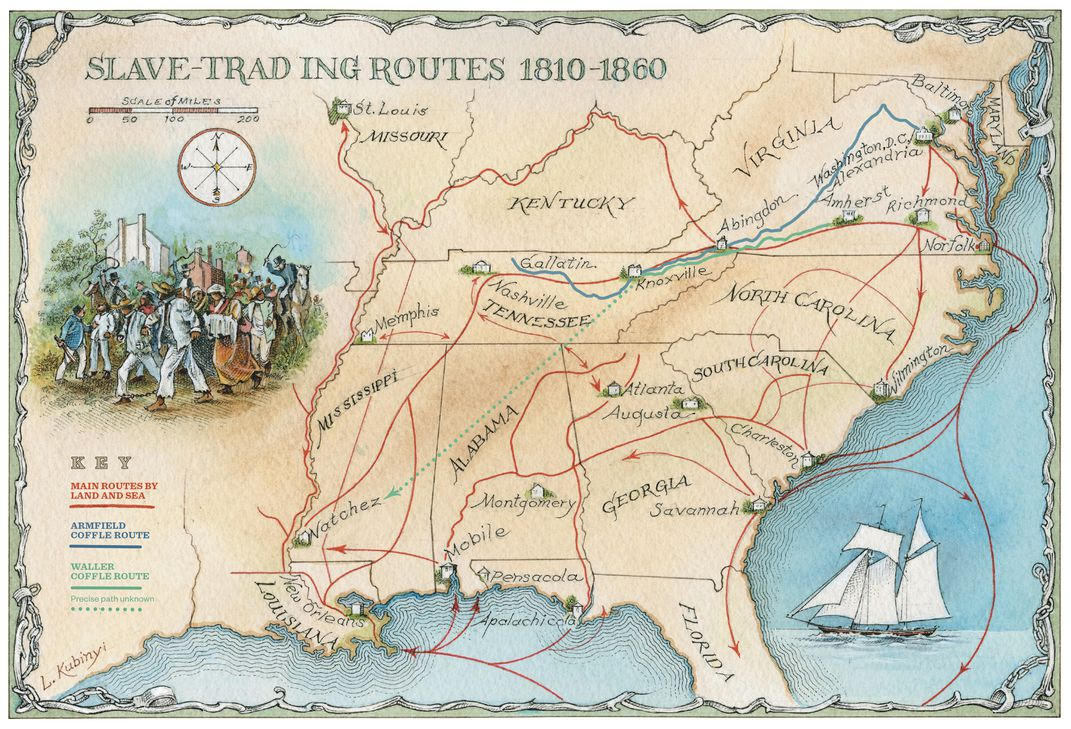

The Mississippi River is literally and figuratively America’s “middle passage.” The river and its offshoots link heartland histories and legacies of racist repression to points north, west, east, and south, downriver through Memphis; the Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana delta regions; New Orleans and beyond to the global atrocities of empire and its transatlantic trades. These legacies are sedimented in river cities like St. Louis through patterns of dislocation and dispossession, migration, resettlement, and continued exclusion here in our (gated) gateway city.

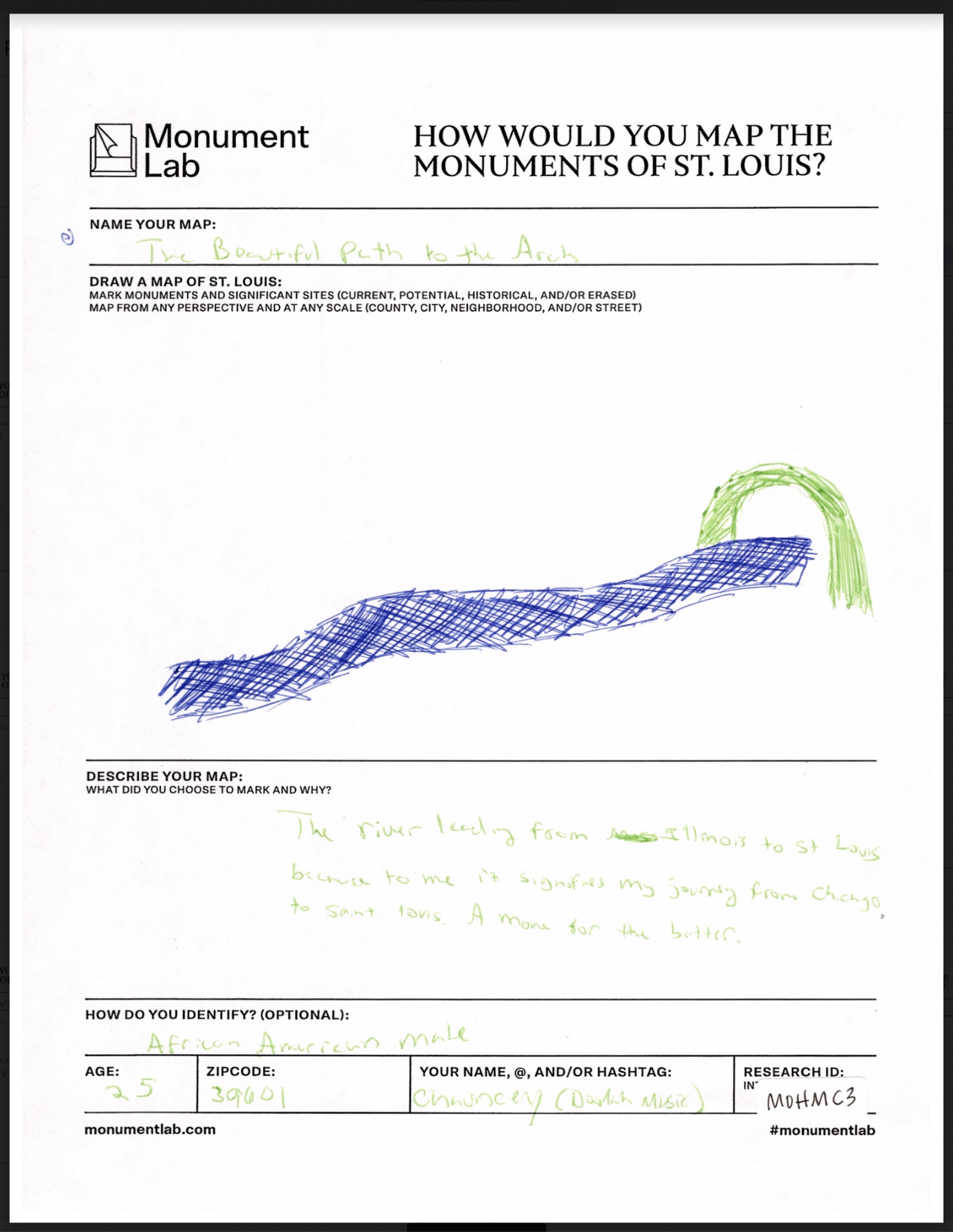

It is in this context that I grew especially fascinated with iconoclasm around the Gateway Arch, its meaning, and importance. The stock reading of St. Louis’ iconic monument is from east to west, and, most importantly, whilst white washing the racial violence of Manifest Destiny with the language of development or expansion. Yet the Arch is more interestingly and accurately read as having many vantages and meanings. The Arch reads differently and no less accurately looking east, literally framing the Mississippi Riviera and race war torn city of East St. Louis, or by looking at it askew, to isolate the murky waters (and cargo) of the Mississippi River, which functions through its many tributaries as "America’s hydrological heart.” The Arch is a memorial to settler colonialism, enslavement, and other histories of extraction central to our national story.

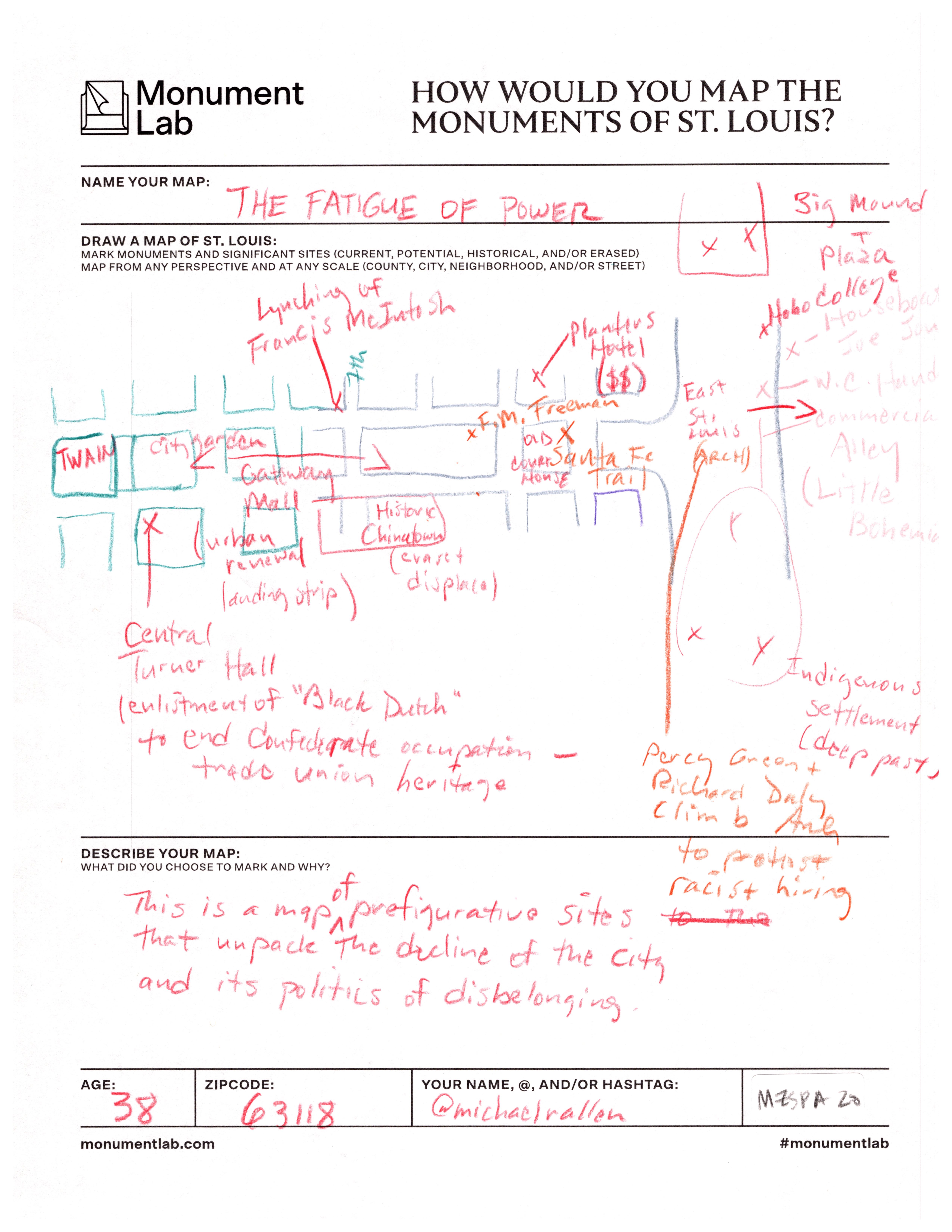

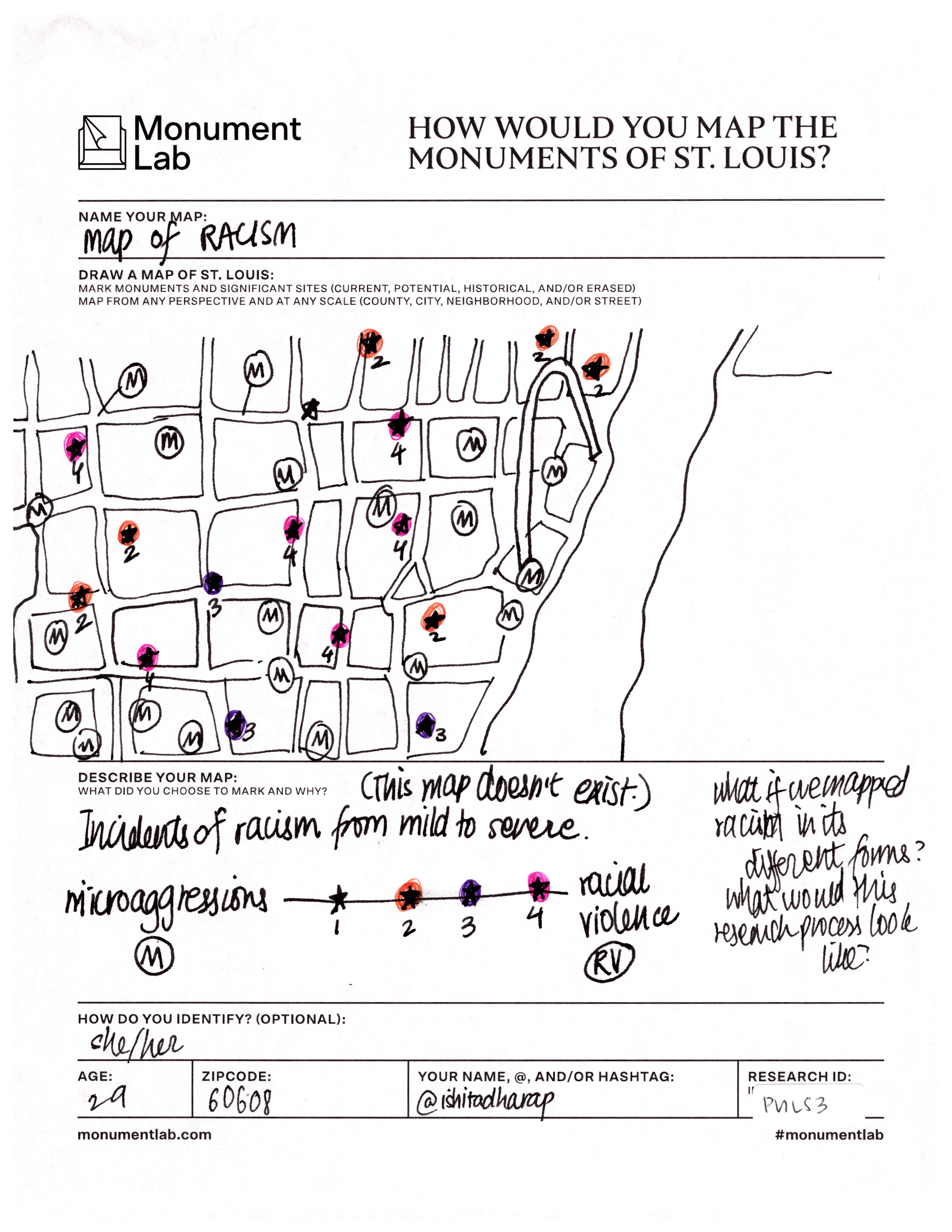

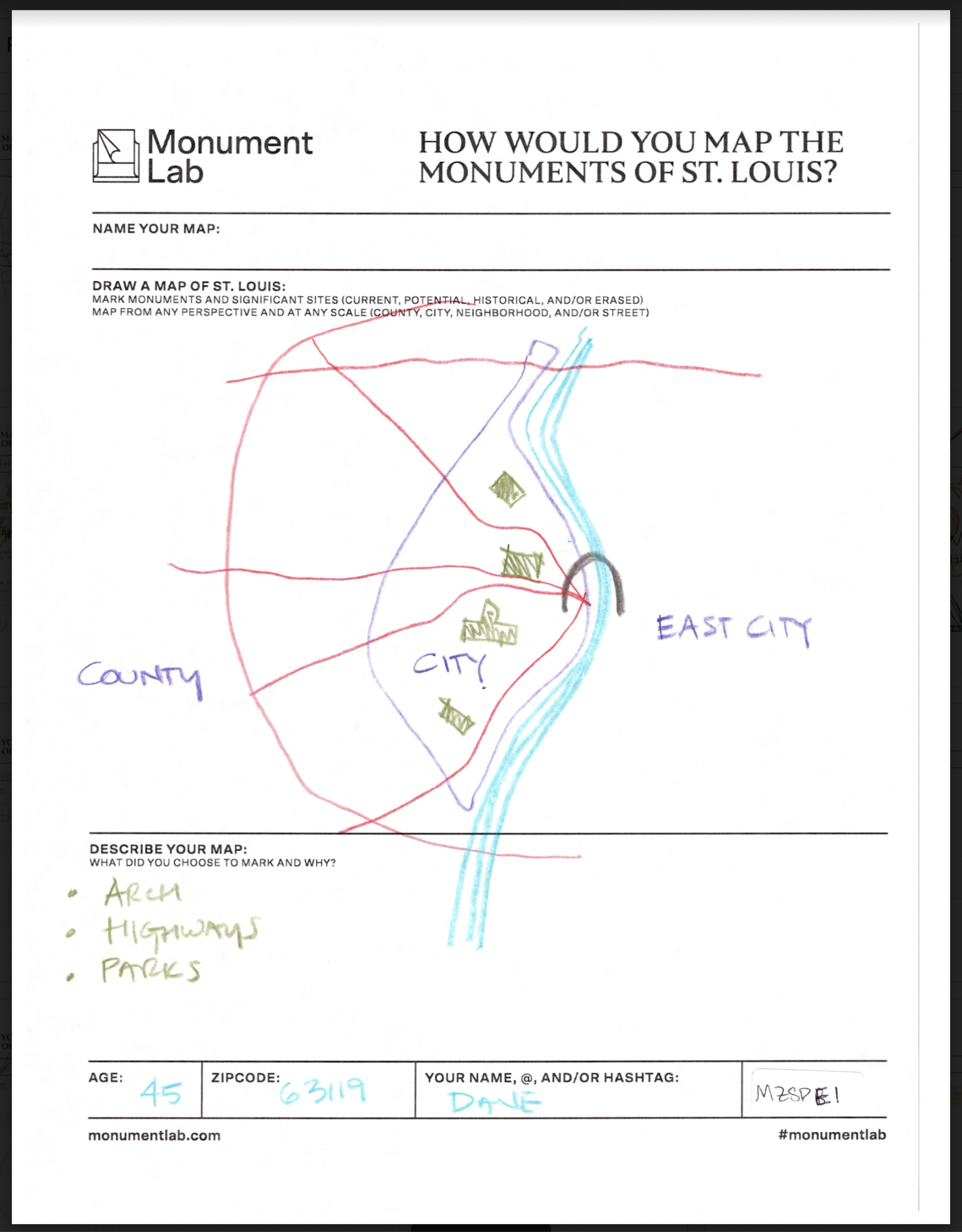

Indeed, some of the most intriguing of the many hundreds of St. Louis project maps are those which include this inherited monument but reposition it, with the Arch drawn straddling the two sides of the river. Like a stretched-out staple, this rotated Arch has the river running through it and strains to keep a broken country together. Virtually all of the other maps including this monument place it more or less accurately, in downtown St. Louis, and most portray it uncritically as a proud symbol of the city. Several other alternative and critical readings of the Arch, map its relation to local histories of racial violence, employment discrimination, and the dispossession and dislocation attendant to urban renewal, without shifting its position.

Yet I am especially struck by several shape-shifting renderings of the Arch straddling the river, centering America’s Middle Passage, and disturbing our relational understanding of St. Louis itself. From this vantage, especially, the Arch becomes a kind of portal, or window into the past, present, and future of empire, the transatlantic trade, and their centuries of recirculation through the nation’s arterial structure, where St. Louis has been critical for its location on the Mississippi and nearby East-West flowing confluences.

Yet I am especially struck by several shape-shifting renderings of the Arch straddling the river, centering America’s Middle Passage, and disturbing our relational understanding of St. Louis itself. From this vantage, especially, the Arch becomes a kind of portal, or window into the past, present, and future of empire, the transatlantic trade, and their centuries of recirculation through the nation’s arterial structure, where St. Louis has been critical for its location on the Mississippi and nearby East-West flowing confluences.

This river-centric Arch invites greater reckoning with the atrocities of “trade,” including histories and legacies of Native American dispossession and cultural genocide, centuries of imperial aggression towards Mexico and throughout the Americas, and the triangular slave trade within the continental U.S., connecting the southeastern coast of Virginia, and the southern artery of New Orleans to the northernmost market in St. Louis, all of which became more vital to the peculiar institution with the abolition of the transatlantic trade in 1808.

While unlikely one foot of the Arch will be swung over the river, the St. Louis iconoclasts illustrate the impermanence of memorial meaning. It is noteworthy in this respect that the Arch has been renamed and reinterpreted in recent vintage. What was inaugurated in 1968 as the Jefferson National Expansion Park is now the Gateway Arch National Park, and more expansively described as “a memorial to Thomas Jefferson's role in opening the West, to the pioneers who helped shape its history, and to Dred Scott who sued for his freedom in the Old Courthouse.” The last of these revised meanings is especially new, a “prosthetic memory" added as a kind of reparative commemorative component, a kind of memory offset, countering the toxic narrative of manifest destiny. One only hopes this reinterpretation will help to redefine our local and national character, somehow turning the gateway arch into a portal for a just future.