“What’s the opposite of Manifest Destiny? It’s a concept I call manifest dismantling. Glimpsing a strange forward-and-backward feeling.

Our idea of progress is so bound up with the idea of putting a new thing in the world that it can feel counterintuitive to equate progress with destruction, removal, and remediation. To make the past live in the present and to do it justice.”

-Jenny Odell, “How to do Nothing”

In the summer of 2018 I invited Monument Lab to organize a project as a counterpoint to the Pulitzer Arts Foundation’s exhibition, Striking Power: Iconoclasm in Ancient Egypt (Mar 22-Aug 11, 2019), which brought together objects intentionally destroyed for religious or political purposes across 4,000 years of history. Though historic in nature, the exhibition underscored how visual culture facilitates narratives of power, asking viewers to look deeper at cultural memory and the creation and destruction of monuments, cultural sites, and memorials across time and place. To make these ideas relevant to St. Louisans and to the contemporary moment, we asked Monument Lab to collaborate on a project about regional power and visual culture.

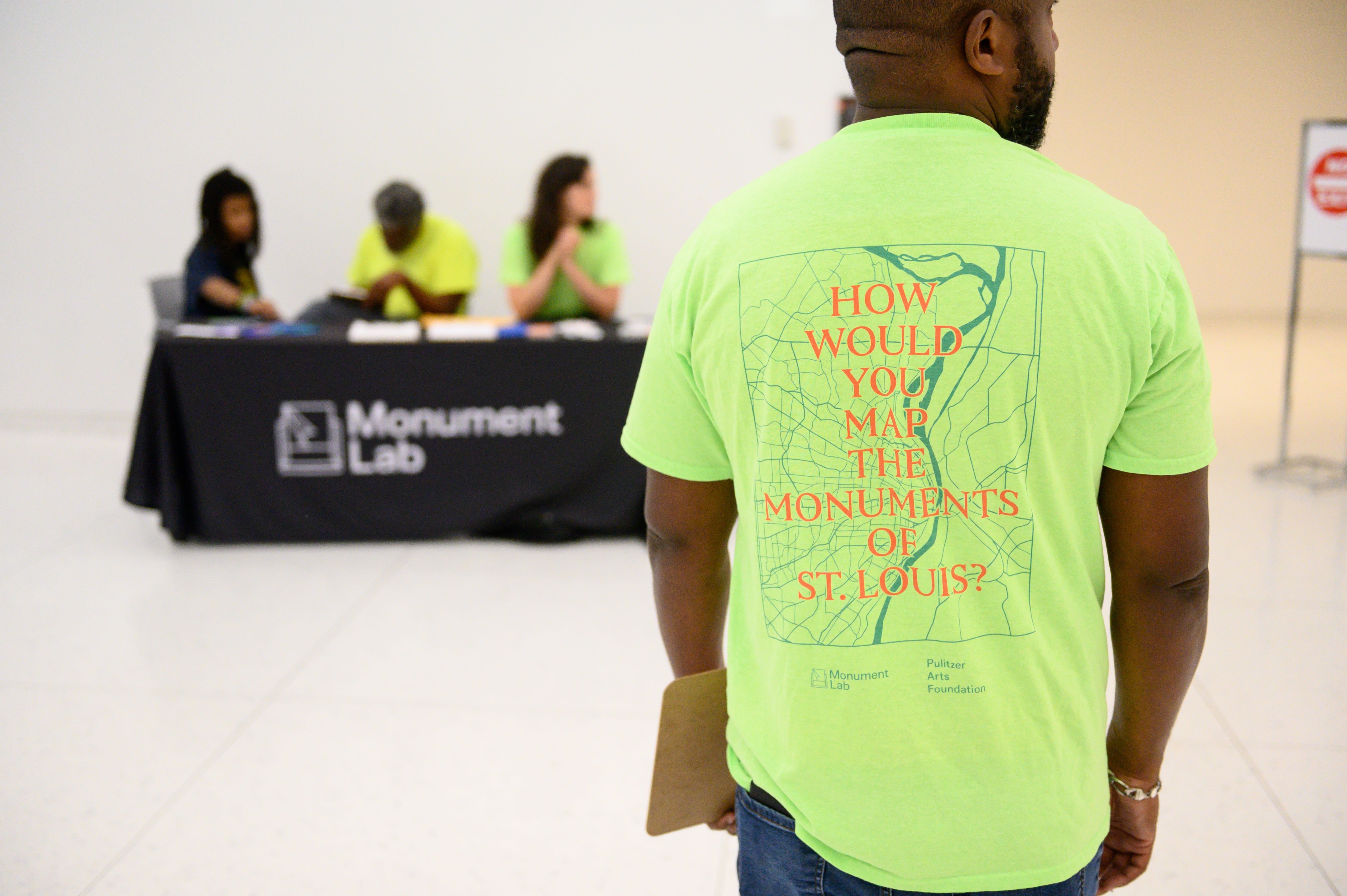

Monument Lab proposed a summer research residency that gathered publicly-sourced inventories of St. Louis’s symbols and sites of memory in order to explore this question: How would you map the monuments of St. Louis? The project, titled Public Iconographies, focused on both existing landmarks and monuments as well as aspects of the city’s current landscape that are not memorialized but are nonetheless part of the public consciousness of the city’s histories of justice and injustice, as well as equity and exclusion.

Working from a research field office at the Pulitzer, Monument Lab and a team of local researchers expanded their work into various communities through research-gathering meet-ups at cultural sites around St. Louis. The team attended 46 events and engaged people from 141 zip codes over three months. Members of the public were invited to participate in the research by submitting their responses in the form of a hand-drawn map. The researchers built an atlas of 750 maps marking both traditional and unofficial sites of memory, whether the monuments—sites, memorials, or landmarks—be existing, potential, historical, or erased. The goals of the project were to explore the relationship between St. Louis’s residents and the city’s inherited symbols as a means to critically explore, represent, and update the iconography of the city.

While the research team collected maps, the Pulitzer staff connected with stakeholders across the city. Hundreds of St. Louisans were willing to draw maps and share their ideas, and we wanted to steward their work by making sure it was in the hands of cultural organizations and public space planners who could put ideas into action. Representatives include colleagues from Washington University in St. Louis, the Missouri Historical Society, the St. Louis Public Library, Great Rivers Greenway, the City of St. Louis, and individual artists and civic leaders. The data is also now publicly accessible. The goal of this effort is to encourage people to engage with the data, and inform exploratory projects that account for social justice as an often unmapped layer of the city.

To reflect on monuments and cultural memory is to reflect on one’s personal experience of the city, albeit a shared story that blends the painful and delightful, the unrecognized and inspired history and future. In the world of social media and demands of the attention economy, sitting with a stranger, having a conversation, and making a drawing is, in many ways, a radical act. There is a deep need to critically reexamine how visual culture informs representations of power in public space, evaluating how the past reflects upon the now and the future, in order to center the voice and values of the community. While the residency focused on individual conversations in public space, social media has counterbalanced the isolation brought on by COVID-19 and sustained relationships, amplified voices, and catalyzed a cultural awakening. It is not a question of virtual space versus in-person conversation, it is about focus, building community, and relationships.

In the last two years the collaboration with Monument Lab has transformed from a public residency and community organizing to social science evaluation and data sharing. In that same time, the local and global contexts have drastically shifted. The project began by investigating the former location of a Confederate monument in Forest Park (removed June 2017), whose lasting presence is a concrete street curb, sod infill, and a dot on park maps. We met with activists and park administrators debating the future of the Christopher Columbus statue in Tower Grove Park and visited Michael Brown’s memorial in nearby Ferguson, Missouri. Conversations continued with creative workers, nonprofits, and University faculty and students.

The project now sits within the context of two pandemics, COVID-19 and systemic violence against BIPOC, whose health crises further demonstrate the social injustices and institutional violence that play out in our everyday lives from access to health care, to equity in our education system, and the murder of Black people under the guise of public safety. Citizens are acting against systems of oppression that have been created and upheld by American institutions, beginning with the genocide of Indigenous people, 250 years of slavery, Jim Crow, and todays prison industrial complex, illustrating the urgency to decolonize minds, policies, and public space.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, the playground one block from my house was wrapped in yellow caution tape with black letters—POLICE LINE DO NOT CROSS—and in opposition, large letters in green spray paint scrawled across the molded plastic climbing wall read, “Rent Strike.” A temporary, unintentional monument that visualizes mobilization and immobilization. This summer, monuments have been torn down by citizens around the world, dumped into rivers, and marked on google maps as “closed,” or unceremoniously removed like the aforementioned Columbus statue.

Indigenous leadership has worked for generations to remove the Columbus statue in St. Louis. In 2019, a task force composed of representatives from Indigenous tribes, Black Lives Matter activists, the Missouri Historical Society, National Park Service, and the St. Louis Art Museum recommended keeping the statue and adding signage to present an accurate historical narrative. Recent uprisings changed minds, and removed the sculpture in May 2020. The now empty plinth at Tower Grove Park demonstrates that collective action can shift representations of power. Change is the vision and work of many people, across disciplines, across time. Change is listening.

These actions demonstrate care and energize the work of dismantling racist systems. Alongside the take-downs, St. Louis activists succeeded in a longstanding campaign for leadership to close the Medium Security Institute known as the Workhouse, notoriously known for inhumane living conditions. The campaign, led by lawyers and activists of ArchCity Defenders, Action St. Louis, and Bail Project St. Louis, among many others, grew directly from the Ferguson uprising in 2014 with the goal to stop the criminalization of poverty and mass incarceration of Black people. The close of the Workhouse is significant and integrally connected to monument removals.

As we move to the future, we often look back to look forward. With Monument Lab and Striking Power, we looked at history to tap into our present moment, to better understand images of power and the power of images. Much of my work at the Pulitzer is about organizing multidisciplinary collaborations in support of artists, ideas, and community that are as much about process as they are about actual creative output. After two years of working with Monument Lab, I am inspired by the research model and vulnerability of the St. Louis mapmakers. I am humbled by the 750 conversations the researchers had with individuals across St. Louis, each one a moment of community connection. I have continued to learn how monuments and creative action in public space can demonstrate that other ways of living, institution-building, and shifting collective memory are possible.