On the 27th of October in 1909, the Asociación Chung Wah was established in the port town of Puntarenas on Costa Rica’s Pacific side by a group of Chinese men. They formed this association more than fifty years after the first indentured laborers from China arrived in Costa Rica in 1855, and twelve years after anti-Chinese legislation in 1897 prohibited Chinese immigration to the country. Today, this association is known as the Asociación China de Puntarenas, and has served as a critical space for Puntarenas’ Chinese community for over a century.

Group photo in front of the Asociación, early 1900s. Collection of the Casa de la Cultura de Puntarenas. Photographed by the author in 2018. Image provided by the author.

I came to know of the Asociación over two summers in 2018 and 2019, as part of my audiovisual project, Los Paisanos del Puerto: Living narratives of the Chinese diaspora in Costa Rica. My first time in the country was 2017, when I spent a semester teaching at a bilingual Spanish-English school. It was the first time I truly experienced the strangeness of being othered. ‘China’ was the gendered and racialized label that trailed me wherever I went and well-meaning people would comment on how well I spoke Spanish. I became curious about the contradictions: while my third grade students would ask me if Chinese people ate dogs or cats, Chinese restaurants selling dishes like arroz cantonés seemed ubiquitous. While I was read immediately as foreign, the barrio chino in the country’s capital city, San José, indicated the sizeable presence of a Chinese community. Prompted by this curiosity, I applied for and received grant funding from Swarthmore College, my alma mater, to photograph and interview the Chinese community in Puntarenas. At the time of my research, there was significant academic literature about the Chinese community in Puntarenas. However, there seemed to be a dearth of images. In response to this, the project culminated in a kaleidoscopic view of the community through documenting their personal photo albums and archival images from the state, in addition to portraits and oral interviews.

Navigating access to the Chinese community in Puntarenas was facilitated by the ease of institutional support and my positionality as a young person of the Chinese diaspora. My professor at the time, Edwin Mayorga, who is chino-nicaragüense, introduced me to Jason Oliver Chang, author of Chino: Anti-Chinese Racism in Mexico, 1880-1940. With these introductions and my Swarthmore College affiliation, I was rapidly connected to a number of scholars – Lai Sai Acón, Susan Chen Mok, Monica DeHart, Lok Siu - who have written about the Chinese diaspora in Costa Rica and Central America. Through Susan, who is part of the Chinese community in Puntarenas herself, I was introduced to Flora Ángela Li Cheng. Meeting Flora was a culture shock: she spoke in rapid fire Spanish yet looked like she could be my grandmother. Wise and abundant with warmth, Flora became my host, guide, substitute grandmother, and confidante during my stay in Puntarenas. Where I was shy, Flora was a notorious tica linda. Together on her landline, we dialed up her numerous friends and family. She would lovingly introduce me as the chinita who was doing the photo project, then proceed to chatter away.

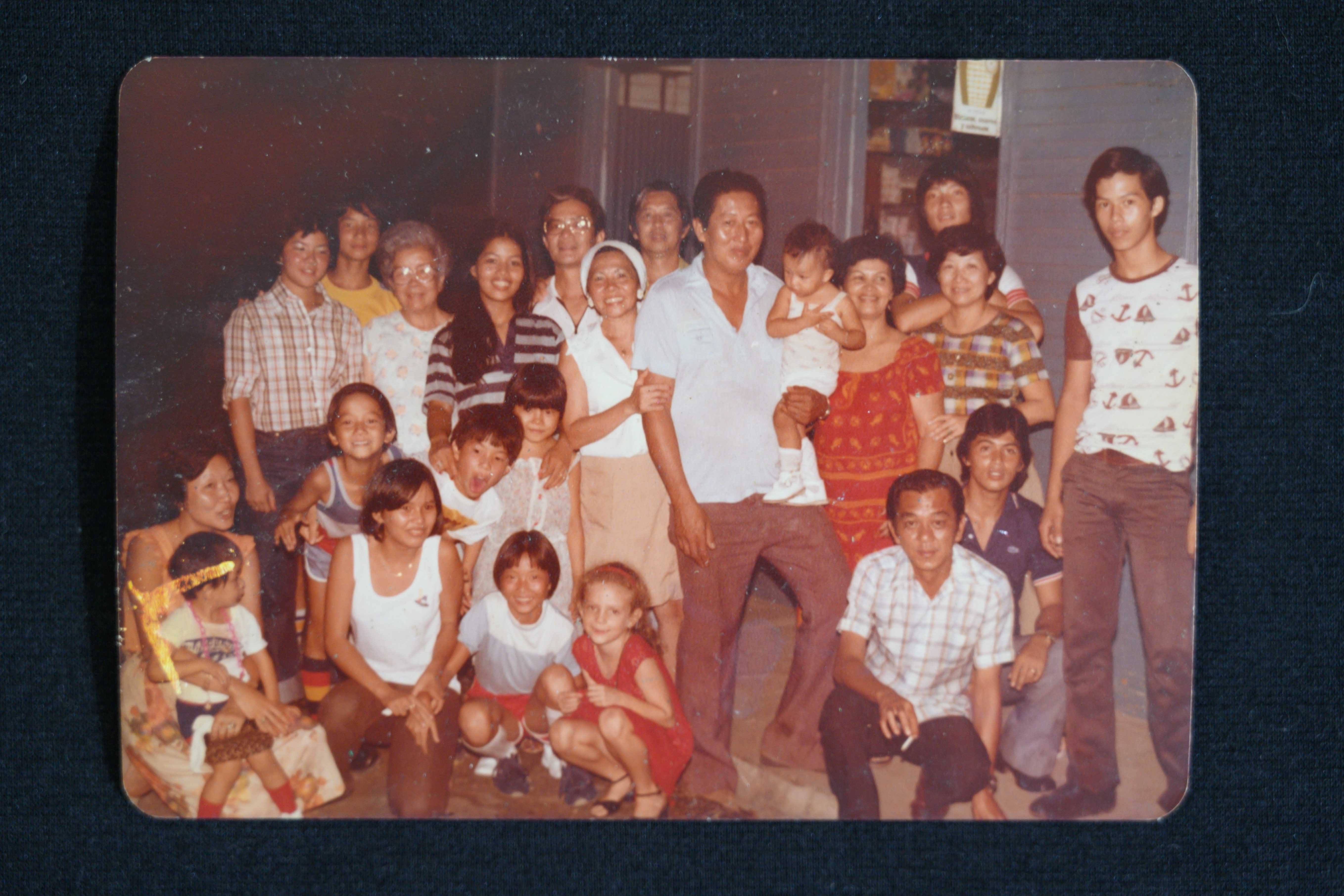

Over the omnipresent hum of electric fans and cold glasses of tea, I started slowly conversing with the paisanos. Collaboratively, we reopened tangible and intangible memories of their Chinese/Costa Rican experiences. I listened raptly to stories of ping pong tournaments, quinceañeras, and Cantonese language lessons. Many of these orbited around the nexus of the Asociación.

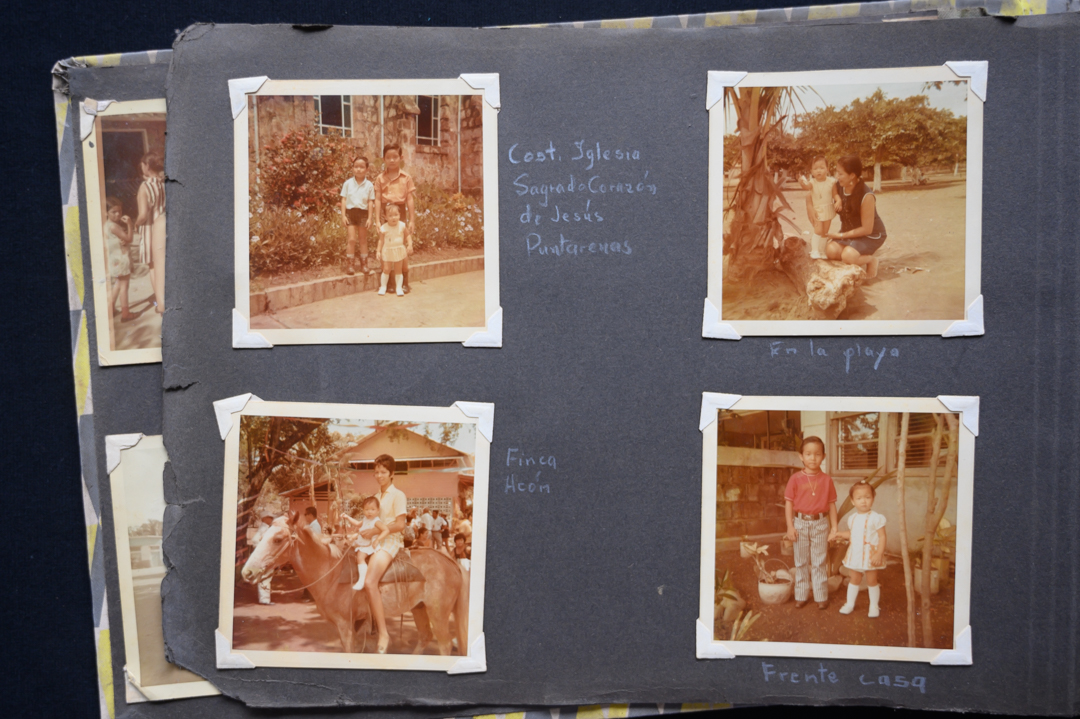

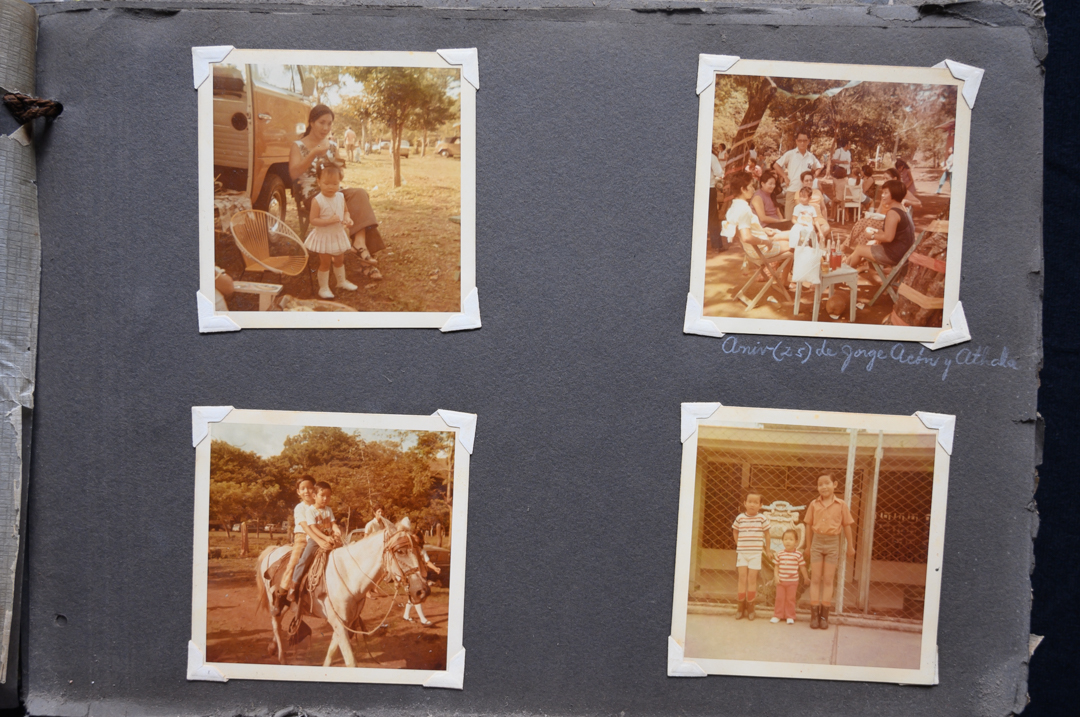

I also requested to see their photo albums. Ever since childhood, I have been obsessed with my own family’s photographs. It was as if, by somehow memorizing the images, I could erase the physical distance and language barriers. Familiarity with the photos acted as a proxy to intimate relationships. In the context of the Chinese diaspora in Puntarenas, I felt a strong emotional pull towards the sepia photographs, their frayed edges, and carefully annotated details. Sometimes, an adult grandchild would be present as their elders brought out the photos. They would remark that it was their first time seeing these images as well. Viewing and documenting the photo albums enabled and extended a sense of kinship and identification for me, as a young woman of the Chinese diaspora.

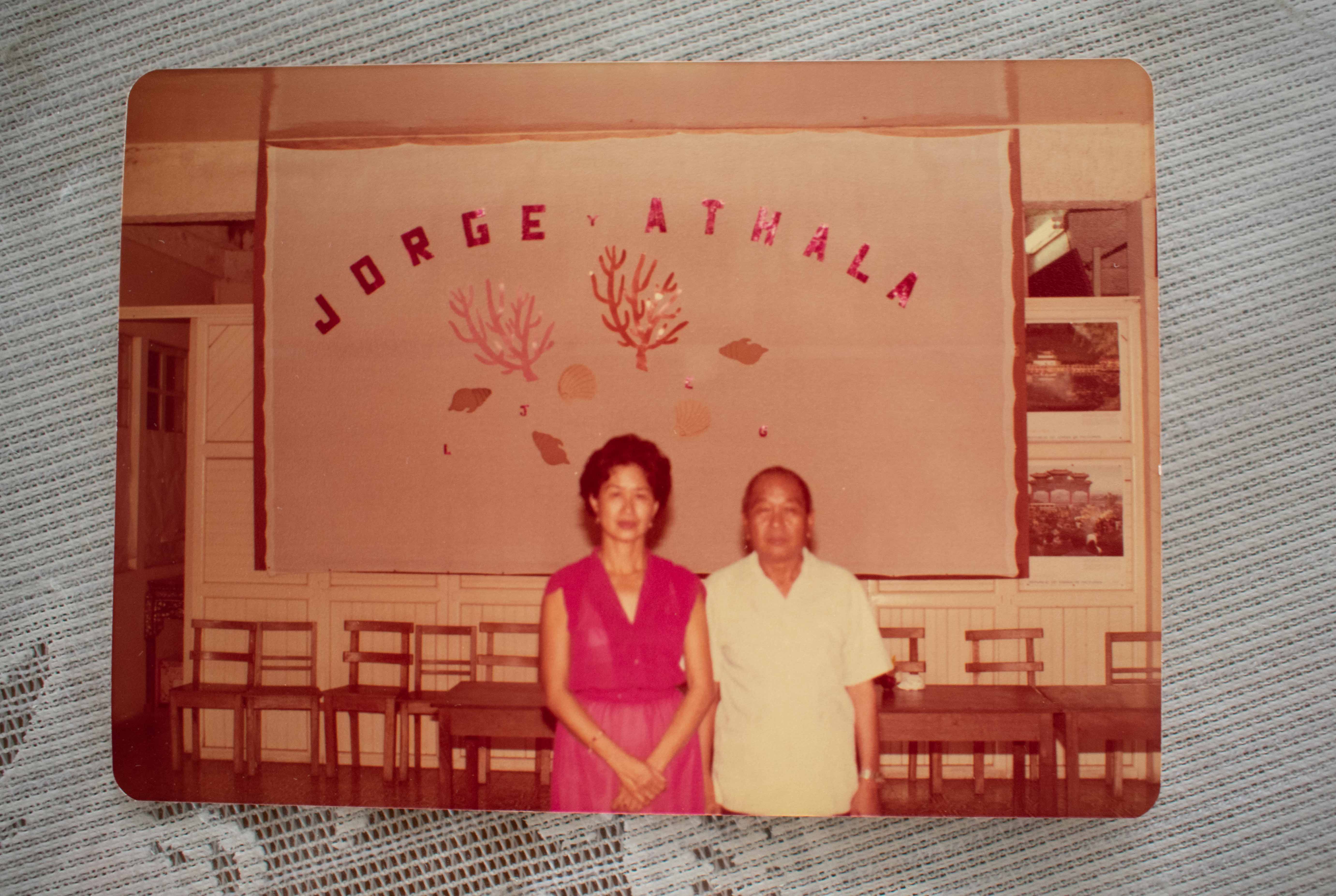

Athala Li Chen and Jorge Acón’s wedding anniversary at the Asociación, date unknown. Collection of Acón family’s photo albums. Photographed by author in 2018. Image provided by the author.

In stark contrast to the present-day barrenness of the Asociación, these images illuminated its prior vitality. The pages of these albums offered glimpses into the Asociación’s textured histories. When I first saw the building in 2018, it was painted a conspicuous shade of pink with bilingual signage on its side - Asociación China de Puntarenas 中華會館. A black and white image from the early 1900s revealed its beginnings as a sparse wooden building. I had needed special permission to bypass its locked gates – testament to how sparingly it was used. Hardly anyone frequented the Asociación anymore.

Preparing for Día de la Independencia at the Asociación. Photographed by the author in 2019. Image provided by the author.

The Asociación China de Puntarenas. Photographed by the author in 2018. Image provided by the author.

Only objects, like old plaques with Chinese calligraphy, occupied the space. A glass office in the back corner encased a set of lonely set of wooden furniture. The muebles, a set of chairs and panels, were intricately carved and decorated with iridescent shells. In old photographs, they are in constant use. They seat the squirming Sánchez children, the youngest of whom is now 83. They peak through Floriana’s quinceañera and Edgar and Luisa’s wedding. The precious furniture was shipped from China at Asociación’s conception, a material link to the home country.

Floriana Sánchez Li’s quinceañera, c. 1980. Collection of the Sánchez family’s photo albums. Photographed by the author in 2019. Image provided by the author.

Sánchez children at the Asociación, c. 1940s. Collection of Sánchez family’s photo albums. Photographed by the author in 2019. Image provided by the author.

Also ubiquitous in the photographs are dubious markers of Chinese heritage and belonging. In addition to individually maintained kinship networks, the Asociación collectively established ties with other Chinese Associations across the Americas, often under the political impetus of supporting the Republic of China (ROC). A consistent motif in the photographs is nationalist imagery, either in the Republican flag of China or the numerous portraits of Sun Yat-Sen. When Costa Rica severed diplomatic ties with Taiwan in 2007, the Asociación followed suit. Nevertheless, Republican slogans remain etched in the Chinese plaques, illegible to a community whose mother tongue is Spanish. The original meaning and ties that their forebears held with these symbols has been lost. What remains is a perpetuation of a past that is no longer legible.

Meeting at the Asociación, date unknown. Collection of the Asociación China de Puntarenas. Photographed by the author in 2019. Image provided by the author.

Edgar Acón Li and Luisa Hernández Lo’s wedding, date unknown. Collection of the Acón family’s photo albums. Photographed by the author in 2018. Image provided by the author.

Perhaps for me, documenting these photos also serves to prevent further loss-- not the loss of anticipating extinction, but loss in the sense of unknowing.

Registro de chinos, libro nº2, abierto en enero de 1922. Collection of the Asociación China de Puntarenas. Photographed by the author in 2018. Image provided by the author.

There exists an inextricable history that photography has with surveillance and control. For many communities, it is connected to a traumatic legacy of being utilized by dominant powers without consent. This is evident in the enforcement of Chinese registries in Costa Rica, as part of national anti-Chinese legislation. Yet this registry exists today as a treasured possession of the Asociación, tactile proof of Chinese existence in Costa Rican history.

I hope that the photographs I have documented and replicated in this piece relate to curation as an act of care, rather than exploitation. In requesting permission and receiving invitations to their photo albums and histories, I hope these relationships evoke the lineage of transnational Chinese diasporic community. On an individual level, china takes on a new meaning as a term of endearment. Flora recounted to me that she only decided to host me when she found out I was also Chinese. My proximity to these narratives and individuals supplants the distance I encounter with my diasporic family in Malaysia. On a broader scale, diasporic Chinese communities have historically been interlinked across borders. They have been united by political causes, beauty pageants, immigration, or familial ties. In showing these images, I hope that they can build identification with the broader transnational Chinese diaspora as well as question the nature of ‘Chineseness’ and Costa Rican national identity.

The Sánchez family and Chango family, c. 1980s. Collection of the Chango family’s photo albums. Photographed by the author in 2019. Image provided by the author.

Yet, like all histories, the narrative I offer through these images is dotted with inconsistencies, ruptures, and interruptions. These photos from the Asociación represent only a segment of the Chinese Costa Rican community in Puntarenas – an intersection of people who have allowed me access to their photos and people who were involved in the Asociación’s activities. Thus, the stories that have been shared through these images are not the full picture. Within these plural narratives are nestled more unknowns.

Acknowledgements: I would like to acknowledge that the Los Paisanos project was made on the lands of the Chorotega and Huetar peoples, and would like to pay my respects to their elders past, present, and emerging.

Gracias a la comunidad china puntarenense por su confianza en compartir sus historias – especialmente a Flora Ángela Li Cheng, Róger Sánchez Li, Susan Chen Mok, Iris Lam Chen, Jorge Acón Li, Emy Sánchez, Irina Castillo Chango, Ilse Chango Trejos.

Thank you to the readers and editors of this essay, for their time and generosity - Patricia Eunji Kim, David Chan Jr, and Alina Wang.

Much appreciation to the grants that financed this project, the Genevieve Ching Wen Lee Grant and Class of 1961 Fund for Arts and Social Change from Swarthmore College, and the Greater Philadelphia Asian Studies Consortium Award.

A sincere thanks to Ron Tarver and Edwin Mayorga, who have gone above and beyond in their care for their students.

Finally, to my parents, Chua Siew Lee and Tang Soon Fatt, for their love.