Creating an environment designed to inspire inspiration is no easy task. It is equivalent to the challenge of creating holy spaces: how does an architect design the sacred? How does one represent inspiration in form? How does one prepare a place for enlightenment to occur? This is the accomplishment of Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute in San Diego. It is architecture designed to cultivate rational and spiritual transcendence—a secular, sacred space in which Kahn manifested metaphors of inspiration in monumentality.

The Salk Institute was founded in 1960 by Jonas Salk (1914-1995), who invented the polio vaccine. It has since served as a research powerhouse for the life sciences. Salk hired Louis Kahn (1901-1974) as the chief architect to design a structure that would unite people “from different disciplines and backgrounds” to explore “the organization and processes of life.” Kahn sought to construct a space that would facilitate collaboration across the sciences as well as foster thought, meditation, and genius. The challenge was to create a space for the greatest scientific minds not only to work, but also to think. It would be, in Kahn’s words, “a lab fit for Picasso.” Science and art were meant to meld at the Salk Institute. Intuition, inspiration, and rational thought ought to blend. Genius must be given space to roam. Kahn’s challenge with the Salk Institute was to seamlessly integrate poetics and science into a transcendent but utilitarian architectural chimera.

Symmetry

The Salk Institute follows a symmetrical Beaux-Arts layout. It is made up of two identical, parallel buildings, each lined with five wings of offices. The two buildings are separated by a wide, concrete courtyard which itself is bisected by a narrow strip of water that drops off into a lower-level fountain and sitting area. The courtyard below ends at a sloping canyon of sandstone Southern California coastal sagebrush which leads out to the Pacific Ocean a half-mile or so away. When one stands at the head of the fountain, one cannot quite see the termination of the courtyard, and the gray concrete seems to meld with the Pacific, as if the whole ocean were pouring into the Salk Institute through this narrow strip of water, or as if the fountain were flowing directly into the ocean. The structure incorporates the ocean, horizon, and sky as integral parts of the architectural whole, or perhaps vice versa—the Salk institute becomes an integral part of the sea and sky.

The overall design of the Salk Institute parallels Thomas Jefferson’s plan for the University of Virginia. At the University of Virginia, Jefferson employed symmetry to reflect neoclassical rationalism: a central lawn flanked with dormitories terminates on one end with the a library (the Rotunda) and on the other end with an open view of the Virginian landscape. The power of Jefferson’s layout depends heavily on the incorporation of the surrounding landscape. By connecting the library to the landscape view, the pursuit of knowledge (the library) is entangled with the larger world, theory to praxis, inward meditation to outward action. Kahn’s open courtyard derives its perspectival force to achieve the same effect. By connecting the inner and outer worlds, Salk (and Jefferson) appeal to the Renaissance conception of universal correspondences, the idea that the microcosm of the earth reflects the macrocosm of the heavens, that all things are connected in some great, cosmic synecdoche. Kahn’s aptly named “Infinity Pool” perspectivally extends into the infinity of the Pacific Ocean, and further to unite with the blue sky. He uses architecture to frame the landscape, and illusion to conjure infinity, which gives viewers a sense of their place in the world. He wanted these distinguished biologists studying the minutiae of microorganisms in petri dishes to remember The Big Picture: that their actions, research, experiments, and ideas might extend well beyond the confines of the laboratories into the infinity beyond, as Jonas Salk’s did. Conversely, Kahn wanted to humble them, to remind them that the universe is big, and individuals are small—the infinity pool works in both directions.

Infinity

Infinity is a quality that relates both to monumentality and inspiration. According to Kahn,

The sense of wonder is so very important to us because it precedes knowing. It precedes knowledge… The immeasurable is the one thing that captivated the mind; the measurable makes little difference.

For Kahn, to comprehend something is to have knowledge of it, and to have knowledge of something is to ruin its mystery. When one looks down the thin stream that divides the courtyard, the illusion of infinite continuation is created as the concrete and horizon blend. Rationalizing the courtyard, measuring and quantifying it potentially destroys the phenomenon. Kahn’s fountain, set within the grid of the courtyard, creates a one-point perspective in concrete and water, the vanishing point disappears in the sea. Kahn gives any person standing in his courtyard the opportunity to experience the sublime, to transgress the empirical, scientific perspective and instead to become captivated by a sense of wonder, to hand oneself over to infinity.

The Salk Institute Infinity Pool, 2014. (Photo by Carol Quaies-Cosby/Salk Institute)

Elements

Kahn musters all four Empedoclean elements (earth, water, fire, air) in the Salk Institute. The element of water cuts through the textured concrete, which is the structural, earth element of the institute. From here, the sky brings us into the element of air and finally, burning in the sky, the sun (fire) illuminates the whole structure. Each element is intertwined with the others. Considering the building as a body, one can read the fountain as a symbol of the flow of energy, the lifeblood of the Salk Institute, while the concrete is the bones, the structural form. The sky then becomes the realm of spirit, the space the courtyard seems to extend infinitely into, while the sun’s rays make the whole structure visible. Kahn claimed that “Integration is the way of nature. We can learn from nature,”—by integrating the primordial elements into the Salk Institute, he achieves the feeling of ancientness and timelessness that undergirds its monumentality.

The Infinity Pool also creates a meditative atmosphere, an architectural strategy Kahn borrowed from Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building in New York City. The Seagram Building, which Kahn described as “a beautiful lady in corsets,” used reflecting pools in front of the skyscraper to attain a temple-like tranquil atmosphere, separating the building from the chaotic aleatory of New York hustle and bustle. Water is integral to the creation of a silent space. And silence, in turn, is integral to meditation necessary for inspiration.

Courtyard rill fountain — Salk Institute, La Jolla, California, 2004. (Photo by Jim Harper)

Light

In a speech, Kahn asked “What slice of the sun does your building have?” He was quoting the poet Wallace Stevens in order to illustrate his belief that structure is defined by light: “Stevens,” Kahn explained, “seemed to tell us that the sun was not aware of its wonder until it struck the side of a building.” He felt light is a magical substance. Light is invisible, undetectable unless it reflects off something. Reciprocally, any object is invisible unless there is light to bounce off it. Space is a void full of unactivated, invisible light. The paradoxical wave-particle duality of light fits it neatly into the realm of the immeasurable, and by extension, the realm of wonder.

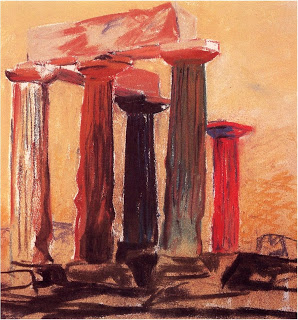

Louis Kahn Sketch, Temple of Apollo, Corinth, 1951. (Photo via Objects-Buildings-Situtations)

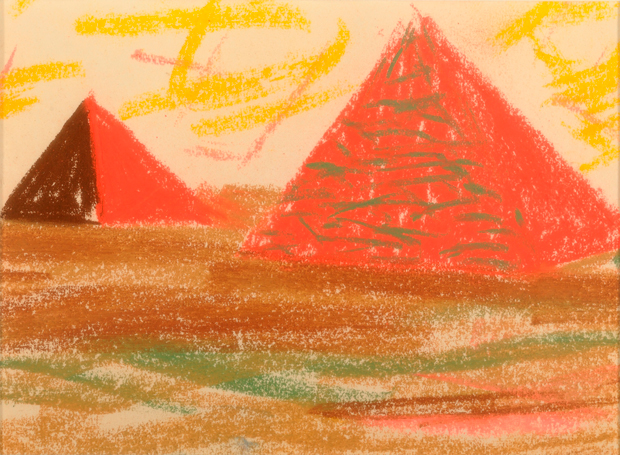

Louis Kahn, Pyramids, No. 8, Egypt, 1951. (Photo via Phaidon)

His sketches from his tour of Greece and Egypt reveal his unique perception of light as it plays across the surfaces of ancient temples, their forms shifting with the lability of the sun. Note how the forms of these ancient temples become colorful, and attain an almost mirage-like ephemerality, as if they might evaporate into steam. Even the pyramids, triumphant symbols of immortality, seem fervid, trembling, mobile, and evanescent. For Kahn, these structures are both permanent and mute, yet they come alive, speak, change colors, moods, even seem to have the power to move when hit by the sun. Light gives life to their form. Kahn’s daughter, Alexandra Tyng, relates the following anecdote regarding Kahn’s fascination with sunlight:

Kahn was intrigued by the nuances of mood created by the time of day, the weather, and the seasons. Scorning the static artificiality of electric light, he would often sit at his desk between the tall windows of his office, waiting until the daylight was completely gone from the room before deigning to reach for the light switch. He believed that the changeable quality of daylight gave life to architecture because one’s relationship to a building changed according to the light surrounding and penetrating it. For this reason, no space was truly a space unless it received the life-giving touch of natural light.

If, as Kahn thought, form is a result of the interplay between an object and light, then we can say that the form of architecture changes depending on variations in light, color, intensity, as a result of the time of day and year. And what better place to observe the power of light!—San Diego has a famously moderate climate; it is sunny almost perennially. To take advantage of these conditions, Kahn angles the windows of his parallel office/lab towers westward toward the sea and setting sun; each window reaches out to grasp its own slice of sun. The whole structure is heliotropic. One can even see in the bird’s-eye Google Maps image how the sunlight crisscrosses the courtyard.

The Salk buildings are offer masterful plays on light, drawing sunshine to even the deepest corners. (Photo via The LA Times)

The Salk buildings are offer masterful plays on light, drawing sunshine to even the deepest corners. (Photo via The LA Times)

Silence

Kahn believed that silence was the opposite of light. Silence is the absence of sound. It is a void, emptiness, nothingness. It can be compared to structure: structure has no form without light. It too is nothing, a void. Without light, structure and silence are merely the unrealized potential for form. In Alexandra Tyng’s words, silence is “the desire to express” whereas light is the “means of expression.” At the point where these two forces meet lies inspiration. Tyng extends the analogy further to compare the relationship between silence and light to a series of binaries: the poetic versus the rational, the yin versus the yang, the feminine versus the masculine:

The poet, who is comfortable in the realm of feeling and intuition, will follow his urge to express for as long as possible before finding the means of expression that would put his images into concrete words. On the other hand, the scientist, who is at home in the rational world, might stay as long as he could in the realm of light, collecting facts and figures to prove his hypothesis before acknowledging its connection with wonder and mystery.

There is something almost Blakeian about Kahn’s sense of duality and paradox in the universe. The idea that something can come from nothing, that the void is a vast expanse of potential that merely needs to be activated or illuminated is a notion that verges on mystical. Inspiration cannot be compelled, coerced, purchased, or in any way forced. The muses can be invoked, demanded, searched for, but more often than not they appear suddenly, briefly, inconveniently, and uninvited—in the middle of the night, say, or halfway through one’s morning commute. Inspiration is an ephemeral phenomenon, an enlightenment in miniature. But the muses cannot come if there is not a place made ready for them.

The courtyard of the Salk Institute is a place uniquely equipped for the arrival of the inspiring muse. Inspiration requires effort, patience, practice, and time—thus, for 363 days of the year, the sun sways north and south along the western horizon of the Pacific as the seasons pass and the Earth tilts on its axis, and it does so out of alignment with the Infinity Pool. Only during the equinoxes does the sun perfectly line up with the fountain. And then—wow—the whole structure takes part in a cosmic alignment, an inspirational equinox. By incorporating the essential element of time into the architectural experience, the building becomes part of time itself, and achieves monumentality through the melding of eternity and form. The whole structure is a monumental metaphor for inspiration, for the rare moment when the muse speaks to the poet (or scientist) and ideas are born from the void.

It has been said that part of the difficulty with discussing architecture is the fact that buildings are, in and of themselves, inexorably mute. So too with the Salk Institute. It is monumental in the gravity of its silence. Yet when the right moment hits, when the light suffuses it and ignites the strip of fountain, the structure comes alive in a transcendent moment of wonder. It is a must-visit for anyone spending time in Southern California.

The Salk Institute Spring Equinox, 2019. (Photo by The Salk Institute)