As an immigrant who has been studying U.S. history for the past three years, I have learned that, in the United States, one must “confront” the history of racism. Americans have made it extremely difficult to share truths about the events that actually happened. I find it shocking that a country with a 400-year history of racial oppression only has a handful of monuments and memorials dedicated to the survivors of slavery, genocide, and colonialism while its city centers, national parks, and rural towns are adorned by nearly 2,000 Confederate symbols. I learned that America whitewashes its history.

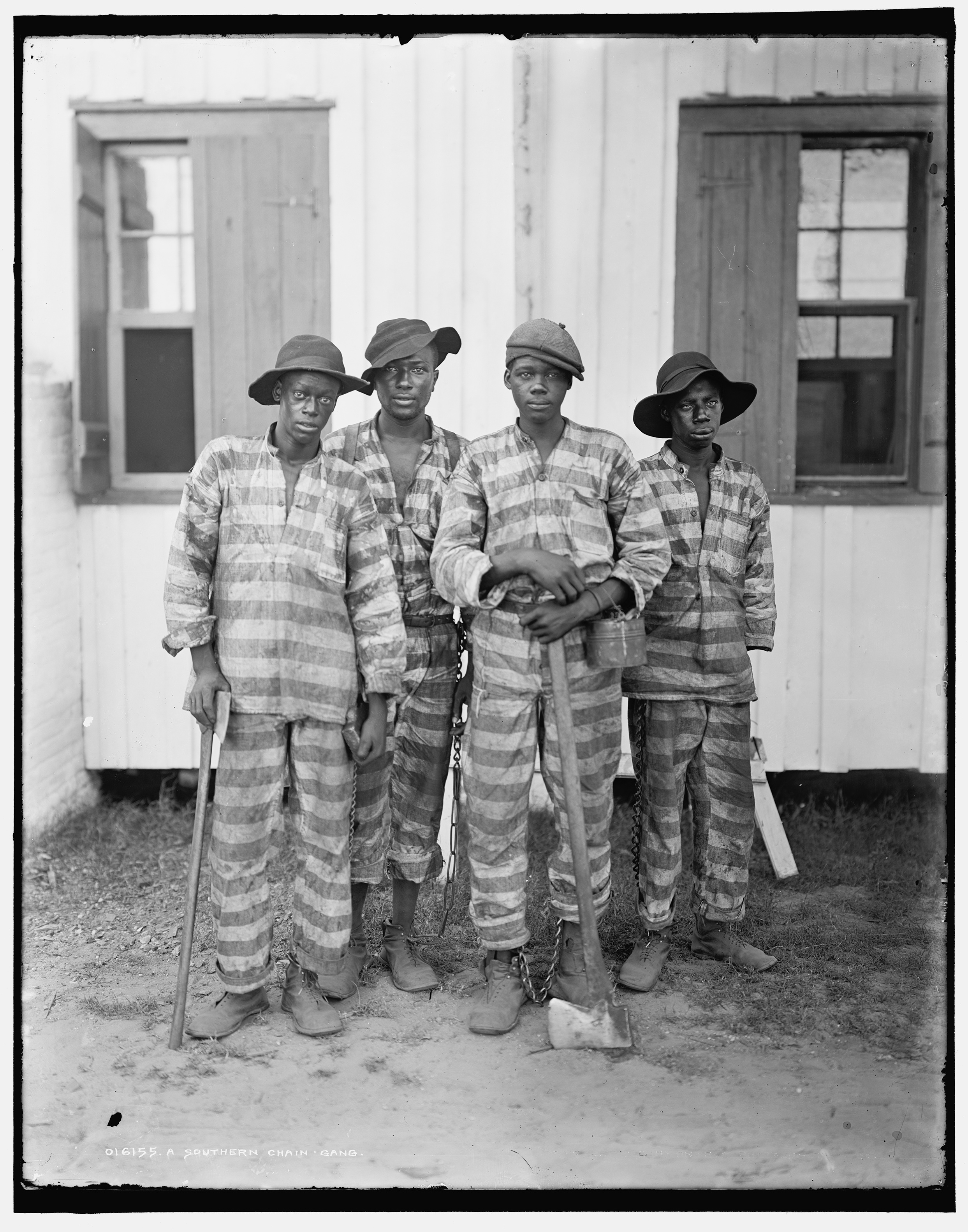

A Southern chain gang. Photo credit: Detroit Publishing Company photograph collection, Library of Congress.

One chapter of history that I’ve come to learn a lot about is convict leasing. I first heard the term when I was an intern at the Equal Justice Initiative a couple years ago and have been raising awareness around it for about a year. Last summer, I won a Soros Equality Fellowship with Mr. Reginald Moore, the founder of the Convict Leasing and Labor Project. Our project focuses on educating the true history behind the 2018 discovery of the “Sugar Land 95”—the remains of 95 African Americans who are believed to have labored under the convict leasing system in Sugar Land, Texas. Forensics revealed that the individuals died on Ellis Camp No. 1, part of Cunningham and Ellis' notorious sugar plantations sometime between 1878 and 1911.

Convict leasing, which began right after the Civil War and didn’t completely end until World War II, was a system in which Southern states leased prisoners to private businesses. It essentially re-enslaved many African Americans— primarily men but also women and even children—who had been deemed free and equal by the Constitution’s 13th Amendment. The fact that the 13th Amendment abolished slavery “except as a punishment for crime” and that the loophole still exists today shock many Americans. Under racially discriminatory laws called the “Black Codes” and “Vagrancy Laws,” thousands of African Americans were convicted and sent to coal mines, lumber mills, sugar plantations, railroad tracks, and roads all over the American South.

Children who were orphaned, removed from negligent parents, or who were juvenile offenders were especially vulnerable after emancipation. They could end up in the convict leasing system as "'apprentices" and fall once more into white planters' hands. Unknown location, ca. 1903. Photo credit: Detroit Publishing Company Collection, Library of Congress.

Convicts unloading a cane car at the Imperial Sugar Company’s mill sometime around 1900. Photo credit: Sugar Land Heritage Foundation.

Often completely innocent of the crimes of which they were accused, these African Americans were forced to work from sunup to sundown, in chains, under the lash and gunpoint of the white guards. Under convict leasing, Black people going about their day could be rounded up, convicted of made-up crimes, separated from their families, processed through an all-white court, and treated with little to no regard to their human value. In his book Texas Tough, historian Robert Perkinson estimates that at least 30,000 died in the convict leasing system across the South over 55 years. One can find blatant and insidious parallels between convict leasing and mass incarceration and the prison-industrial complex. As Bryan Stevenson says, "slavery did not end in 1865. It just evolved." However, convict leasing rarely appears in history textbooks. The generational loss and trauma in Black families is left unexamined.

Even after the 1912 ban on Texas’ convict leasing system, the prisoners were put to work. The state-owned prison farms continued to expand well into the 1950s. Ellis Prison Farm, Texas from the series Inside the Wire, 1978. Bruce Jackson. (printed 2017) (Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York. Gift of the artist, 2017) Photo credit: Albright Knox.

Without ever learning about convict leasing, how can Americans make sense of the discovery of a mass gravesite in a prosperous suburban town? Will the public sweep these uncomfortable truths under the rug again?

Commemorating the “Sugar Land 95”

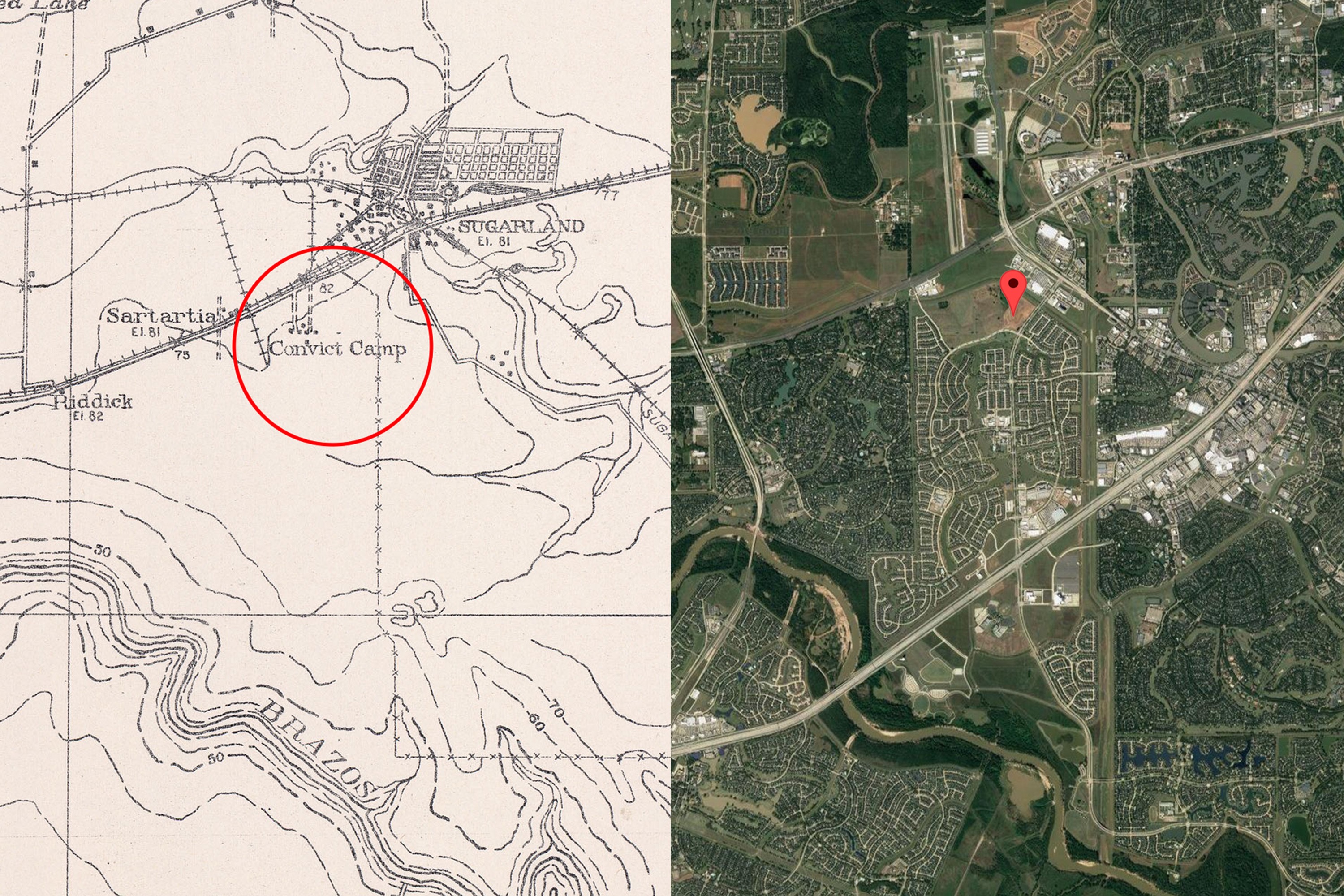

Rapid development quickly erased the history and memory of Sugar Land, Texas. The site where the Sugar Land 95 were found aligns with the location of Ellis Camp No. 1 and later the Imperial State Prison Farm. Photo credits: Left Sugar Land, 1915, USGS map, Center for American History, University of Texas / Right Google Map.

The land where the 95 African American remains were unearthed during construction is owned by the Fort Bend Independent School District, which purchased this former convict camp and state prison land in 2011 and has been accused of mishandling the remains. At the time of writing, Fort Bend ISD continues to own and operate this cemetery unilaterally against community wishes. Moreover, there is no historical marker or other information at the site that tells the history of what happened there. They have even renamed the site with one that is unrelated to the history of convict leasing.

The Sugar Land 95’s reburial site, June 11th, 2020. Photo credit: Barbara Jones

This decision exemplifies the legacy of hiding behind a carefully constructed identity that draws upon the past selectively. Instead of acknowledging its racist past, the city of Sugar Land has offered a whitewashed narrative as its history. The city, state and related industries, such as Imperial Sugar, have worked assiduously to distance themselves from their tortured past. At the Sugar Land Town Square, a shopping and corporate center anchored by city hall that opened in 2004, an equestrian monument of Stephen F. Austin honors him as the “Father of Texas,” inspiring young Texans to become pioneers like him. In this plaza, Austin’s history of bringing slavery to Texas (which was a Mexican territory at the time), massacring native people, and going to war with anti-slavery Mexico is unchallenged. The sentiment is not unusual—in Sugar Land or elsewhere in Texas, and in cities across the U.S.

Today, many residents of Sugar Land do not know this history about their home. More than a quarter of the residents in Fort Bend County are foreign-born, many of whom immigrated for their shot at the American Dream. As the demographic changes, memories of the place have also been rewritten, forgotten. Some deny the possibility of finding more unmarked gravesites like the Sugar Land 95. Yet the residents of Sugar Land, a place literally built on top of massive prison farms, need to be able to listen to multiple narratives about what has shaped their homes.

Ballerinas Kennedy George, 14, and Ava Holloway, 14, pose in front of a monument of Confederate general Robert E Lee in Richmond, Virginia, after Governor Ralph Northam ordered its removal. Photo credit: Julia Rendleman/Reuters; Source: Julia Rendleman.

In recent months, the legacies of monuments to enslavers and colonizers have become incredibly visible. Anti-racist movements across the world after George Floyd’s murder have refocused public attention to monuments that celebrate Confederate figures or European colonizers. Some of them are torn down by emphatic protestors and others removed by city leaders. This powerful movement has successfully compelled institutions to take down monuments that have withstood years of criticism.

To those celebrating the removal of Confederate monuments, how might we sustain this movement in the face of retaliation and against the forces of whitewashing history?

In one of the conversations the interns had with EJI’s founder Bryan Stevenson, he told us that the battle exists outside the courts too: in the public sphere, in the narratives, and in our collective memories. Upholding racial justice through law and tearing down Confederate monuments by public participation are important and necessary. However, winning every legal battle or removing every single one of these Confederate symbols will not end racism or the ideology of white supremacy. Missing chapters need to be taught in schools, made visible in public spaces, and commemorated through national holidays.

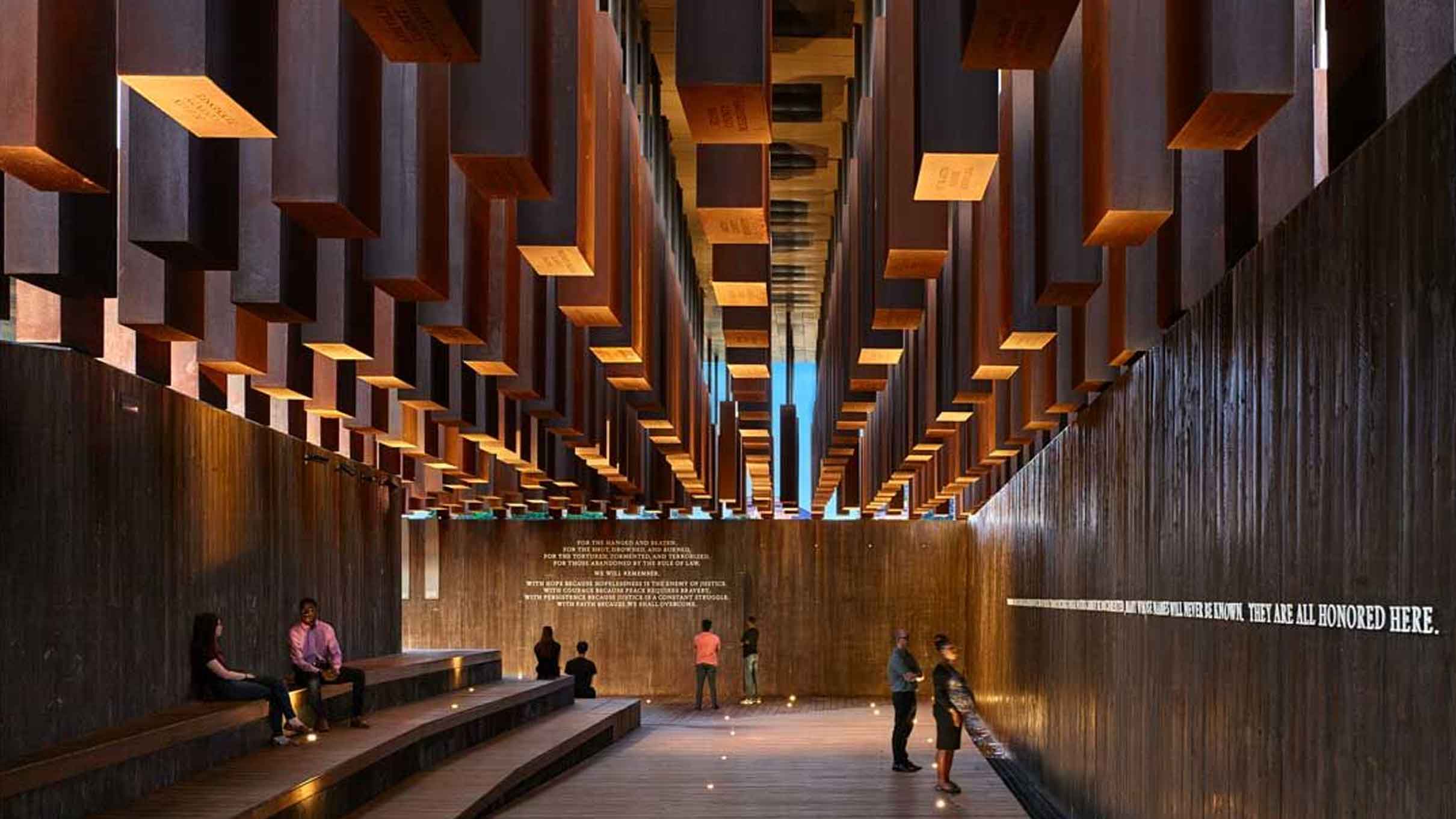

EJI’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama (Photo credit: Alan Karchmre/Mass Design Group )

Americans must find the hidden chapters of their history and really begin to understand the legacy of racial oppression that has strengthened the walls of white supremacy. A version of history that omits these chapters has stolen a chance for the nation to learn from it, and to fix what has been broken by it. As Americans seek to dismantle Confederate monuments, they must also actively create new monuments and narratives that broaden their understanding of justice, democracy, and humanity. I believe that building a memorial dedicated to victims and survivors of convict leasing in Sugar Land, Texas is a step in the right direction.

To learn more about Convict Leasing and Labor Project’s work, check out our Juneteenth report, Convict Leasing in America: Unearthing the Truth of the “Sugar Land 95.”