Andrea Carlson (Grand Portage Ojibwe) is a visual artist currently living in Chicago, Illinois. Through painting and drawing, Carlson cites entangled cultural narratives and institutional authority relating to objects based on the merit of possession and display. Current research activities include Indigenous Futurism and assimilation metaphors in film. Her work has been acquired by institutions such as the British Museum, the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and the National Gallery of Canada. Carlson was a 2008 McKnight Fellow and a 2017 Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters and Sculptors grant recipient.

JeeYeun Lee: You have done a number of large-scale works that function in the space between monuments, memorials, and public art. A few years ago, you had two projects in the Twin Cities: the WATER IS LIFE train wrap, and The Uncompromising Hand: Remembering Spirit Island video projection and installation. Red Exit is up right now at the Whitney Museum, and a new large-scale piece has just been installed on the Chicago Riverwalk. Can you talk a bit about each of these pieces and what motivates you to make work for public spaces?

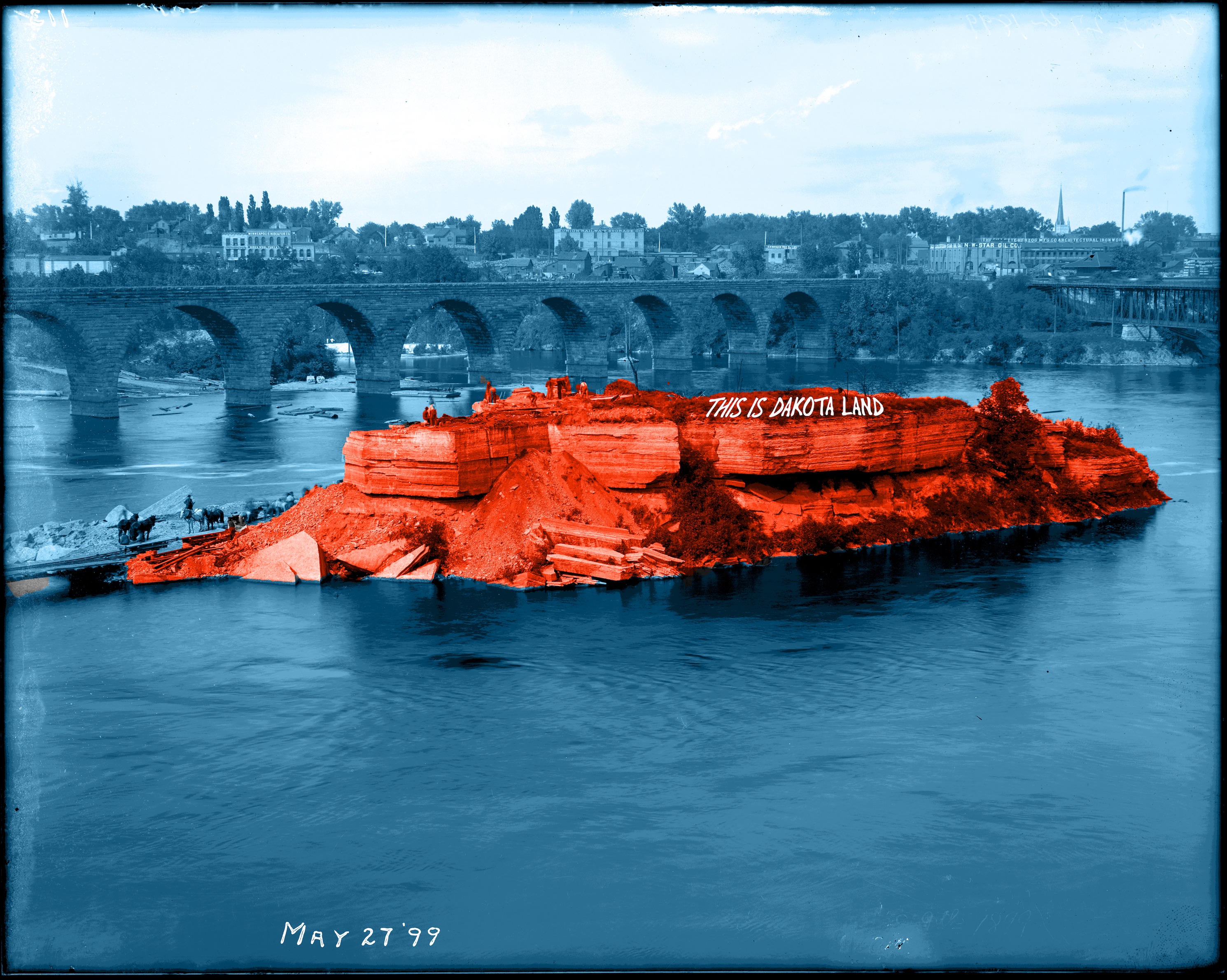

Andrea Carlson: The Uncompromising Hand: Remembering Spirit Island will always be close to my heart. That piece addressed the historic destruction of an island in the Mississippi River that was revered by the Dakota people. Following the Dakota War of 1862 the island was quarried for decades by settlers. The destruction of Spirit Island added insult to injury for the Dakota people who were forcibly removed and living in exile. The last remaining bit of the island was removed and dredged to create a canal for the St. Anthony Lock and Dam in 1963. For my piece, I projected images of the island onto the lock wall with Ojibwe and Dakota place names for the river and island scrolling across in the direction of the river. SInce the piece was temporary, I wrote an essay about the piece that includes some of the history of Spirit Island and my motivations for making the work. I felt that essay is the lasting, archival part of that temporary artwork.

Northern Lights.mn had commissioned The Uncompromising Hand, and they commissioned the Water is Life train wrap along with the support of MetroTransit. I was told when I was working on the design for the train that I couldn’t include political text, but the theme of the Northern Spark festival that [the Water is Life] train wrap was a part of was on global warming. I was assured that global warming wasn’t “political” per se, because the Minnesota legislature had declared the issue ‘settled science.’ We don’t need to go into how the word “settled” becomes an adjective as a final state or end-all. That is its own discussion. I came back with the Water is Life text all over the design for the train wrap. The director at that time said, “no political texts though” and I replied, “it is ‘settled’ science.” He readily agreed and made a case for it to MetroTransit. So it happened. The train was wrapped with Dakota, Ojibwe and English texts and “Water is Life” was on the train for several months.

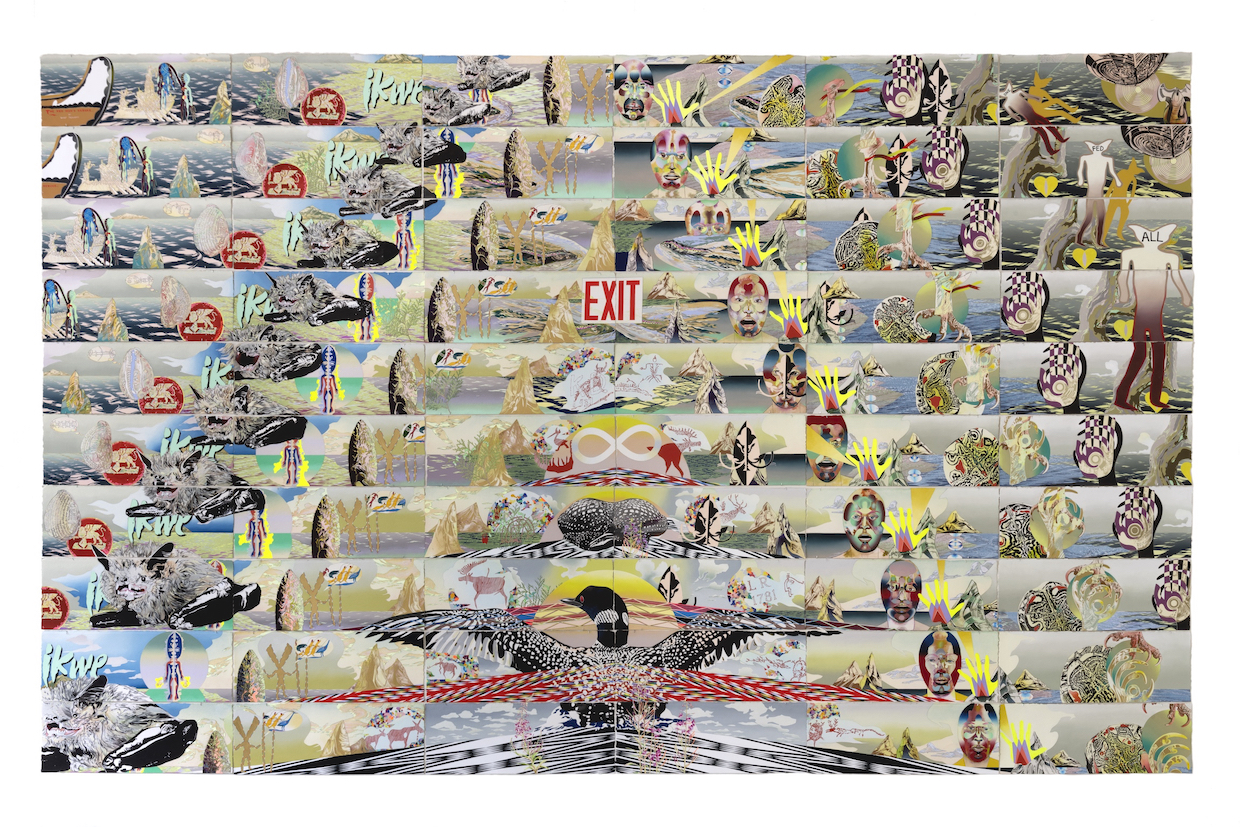

Red Exit is more in keeping with my studio practice. It is about the Anishinaabe/Algonquin re-creation or Earth Diver narrative that centers on the themes of survival, transformation, regeneration, and healing. A large billboard with this image is currently displayed in Manhattan, in the context of the end of the pandemic that disproportionately harmed people in New York. The renewal references in Red Exit seem fitting in that context.

The Chicago Riverwalk piece is a vehicle for the phrases “Bodéwadmikik ėthë yéyék – You are on Potawatomi land” because the statement is both true and displayed near the former sandbar in the Chicago River that lends its name to the Sandbar Decision. In that case, the Supreme Court of the United States effectively denied the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi ownership of the unceded land that was built into the lake by settlers. The court of that time unsurprisingly sided with settlers and ruled that the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi “abandoned” the land. Of course, that language is particularly disturbing when one considers that so many Potawatomi people were forced off their land and to walk the Trail of Death.

These outdoor artworks are all meant to reaffirm Native people where they live and where they seem invisible, which is often the case in urban environments. For example, I want a Pokagon Band of Potawatomi person to stumble upon giant red letters that say “You are on Potawatomi Land” and feel seen, loved, cherished, and validated in downtown Chicago. I want Non-Natives to be witness to this statement too, and to be implicated by it. These public pieces are also made with community consent and support -- not an exhaustive survey because I typically take on that aspect of my projects for myself, but it is important to not speak for or over the community being acknowledged.

JL: What do you think happens when Indigenous artists claim visible public space, inscribe Indigeneity into the contemporary landscape and culture? What does this type of action do?

AC: I think that the idea of public space was supposed to be a good thing, but like many good things, it was also a means to justify bad things. For example, stealing Native land and turning it into public land is still stealing. Public use doesn’t erase that underlying fact. Placing a statue of [Christopher] Columbus on stolen land further adds insult to injury because it is putting an image of a thief and prolific murderer of Indigenous people on stolen Indigenous land. Some suggest that monuments of Native heroes should be erected where monuments of settler-heroes were removed. Would settler land-grab property be a better stage for a monument of an Indigenous hero? Perhaps. But that shouldn’t be seen as justice until the land is returned.

I am often nervous that my art might be seen as some sort of justice to a place. My outdoor artwork might work towards honesty, but it is not justice. Justice might come in the form of returning the land, settler cities could reestablish diplomatic relationships with Native governments, or at a federal level the U.S. could engage in treaty-making again so Native nations can decide what form justice should come in. If my artworks can help normalize the presence of Native people, that is the most I can ask for. But don’t look to my work for reconciliation.

JL: Can you talk about how you view your work in relation to the categories of monuments, memorials, and public art, and whether you think the categorization is ever useful?

AC: My work outdoors tends to be temporary installations, whereas the settler monuments that are currently being discussed across what is now the United States are made out of materials of permanence, such as stone, metal, concrete. These larger, long-term commitments to outdoor displays haven’t been available to me, but it is important to note that all things outside are vulnerable to removal and destruction. Take for example all of the beautiful effigy mounds in the shapes of lizards, turtles, and cranes that used to cover much of what is now Wisconsin. Many of them were memorials. They were turned under by the settler plow and carved up by archeologists and miners alike, buildings were placed upon them. Our petroglyphs get destroyed by geologists drills, by spray paint, by people out to take from our venerated places. Even Mount Rushmore was the Lakota Tȟuŋkášila Šákpe (The Six Grandfathers) before it was defaced with those faces. Because of this, I have no interest in participating in monument-making. Don’t get me wrong, I love seeing Native things in urban environments, I love visibility for the people. But for now, I’ll continue to work in a temporary, site-specific capacity. Permanence should come in the form of honoring treaties “as long as the grass grows upon the earth.”

JL: You locate your work in the space of Indigenous futurism and you’ve written about it a fair amount: can you talk about how you define the concept, and why it’s important to you?

AC: Indigenous Futurism(s) is imagining ourselves in places where we have been written out, imagining ourselves in robust ways. We might give up the term eventually, but if I go to a contemporary museum and I’m not seeing work by Native artists, I’m going to imagine us there. But sometimes I have to imagine us out of a place too. Anthropological, or what are sometimes referred to as encyclopedic museums are often full of Native ancestors -- the bones that were removed from our graves. For me, returning them to the earth is also Indigenous Futurism. They were placed in the ground by our ancestors, but the settlers desecrated their graves. The future is their return to the earth, the future is a circle where our languages thrive and knowledge restored, reinforced, of course, with augmented reality, glitter, and video game technology. My own art is a bit more analog, but I’m so happy to be able to have artists around me under a term where we can find a collective footing.

JL: Let’s talk about place. You came to Chicago five years ago from the Twin Cities. What differences or similarities do you see between the two places in terms of accounting for Native land and life? In my relatively uninformed perspective, I see Minnesota as a place where mainstream reckoning, or at least acknowledgement, of Native peoples has taken place for longer than in Chicago, partly because of the presence of reservations in that state, whereas Illinois has no federally recognized tribes. Do you feel the difference in Chicago? Has it affected your work or your practice in any way?

AC: My art has been profoundly impacted by moving to Chicago, mostly because I’m trying to get into the studio. I’m also working with some artists to open up the Center for Native Futures so Native artists can have some walls to show on and a place to make work in proximity to each other. I do miss Minneapolis with all my heart. One of my friends told me that if I moved back I wouldn’t be returning to the same city, everything has changed since the murder of George Floyd. I have been back several times and it does seem like the veneer of “Minnesota nice” is slipping. I’m very proud of the police abolition movement in Minneapolis.

I went to school at the University of Minnesota and got a degree in American Indian Studies in one of the oldest programs. If Cleveland doesn’t have a say in the matter, Minneapolis is where the American Indian Movement was established. It remains a great place for Native activism. I learned my language there, and the Native arts community is one of love and support.

I can’t speak so knowledgeably about Chicago because I’m truly an outsider. One must have to be born here to call it home, I think. The first American Indian Center was established in Chicago, but financial support for Native initiatives seems to be very low. I’ve been bullied here online and I’ve never experienced that before. The Native mascot thing is still a problem here. The lack of Indigenous Peoples Day and continuation of Columbus Day parades are incredibly disgusting. Native people are fighting against the indignities that shameless settlers continue to advocate for here. That being said, Chicago is home to generous Native artists, poets, and scholars who are committed to harm reduction, and with them I have found a sense of belonging. It is true that Illinois has no reservations, and there is substantial leverage that comes with having Native nations within a state’s geographic location. It is very likely that what is now Illinois, or within its state lines, we will have land returned to Native nations, and with it our sovereignty, and diplomacy. This is in our near future and it will hopefully aid in Chicago’s healing.

JL: About your new piece that just got installed on the Chicago Riverwalk: can you talk about what you hope will happen there? How has your research on Chicago figured into this work?

AC: I live on unceded Potawatomi land. Sure, there were many Anishinaabe folks and Hochunk people all over Zhegagoynak (Chicago in Potawatomi language), but the area of lakefront that was filled to create “new land” is unceded. The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi came back for it. Because of that fact, the fact that they said “No, you don’t get to do that. That wasn’t part of the agreement” means that the land claim is theirs. If the #LandBack movement means that the land is returned to one nation, let it be the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi. Or at least they should have the right of first refusal when it comes to the lakefront. See, this is what Indigenous Futurists do—we imagine bigger than skyscrapers, and no skyscrapers at all.

JL: Indigenous languages feature prominently in your public work. The train wrap, the Spirit Island piece, some videos you’ve created with collaborators, and upcoming work all highlight words and phrases in various Indigenous languages. I know you studied and are a speaker of Anishinaabemowin. Can you talk about how you think about language and text in your work, what the significance is? You also use a lot of English-language text embedded into the images in various pieces -- how does this interact with your use of Indigenous languages?

AC: When I was working towards a degree in American Indian Studies from the University of Minnesota I spent years learning Ojibwemowin (the Ojibwe language). One of my classmates, Aasamaanakwut, said that he was riding the bus and noticed the various languages on the advertisements representing the major languages spoken in the Twin Cities, but not the languages of that land: Dakota, Hochunk, and Ojibwe. We were trying our hardest to learn our language and we weren't seeing it in our environments, our language wasn’t reinforced in the very place where it was taken from us. When I started making temporary public artworks, I used my classmate’s observations as a guiding narrative. I wanted to see Indigenous languages in public. Each of these public works has a language component because that is within my purview and I love our languages. English is there for accessibility or direct references only.

JL: What is your process when it comes to research? In your writing, you go quite in-depth into histories and stories of people and places. How do you go about doing the research, and how does it figure into your practice overall?

AC: Sometimes I don’t even realize that I am researching something. I’ll pay attention and pieces of a story will start to stick together. I’ll give a lecture and people will come up to me afterwards and spill their guts about their related observations or research. I’ll go to conferences and learn about what other artists or researchers are learning. This is to say that I've been brewing information over the years and with community help, I enjoy taking my time when researching a topic. Usually when I’m ready and an opportunity presents itself, I’ll make it work.

When it comes to land, Native and Indigenous artists have a special relationship with it or, in the very least, a special context with it. Many non-Native artists and people are drawn to conversations about colonization, decolonization, and earthworks, but it is important to avoid replicating settler-colonial tactics and assumptions when it comes to the land. How do we all become as sensitive as possible to these colonial frameworks that are continually taught to us? Is there a way that artists can address the land without displacing, erasing, and exploiting Indigenous people, or other Indigenous people if the artist is Indigenous? As both a Native and European-origin artist, I have not fully answered these questions for myself, and I will keep interrogating the sensitivity of my work as it relates to the land and a collective sense of belonging.