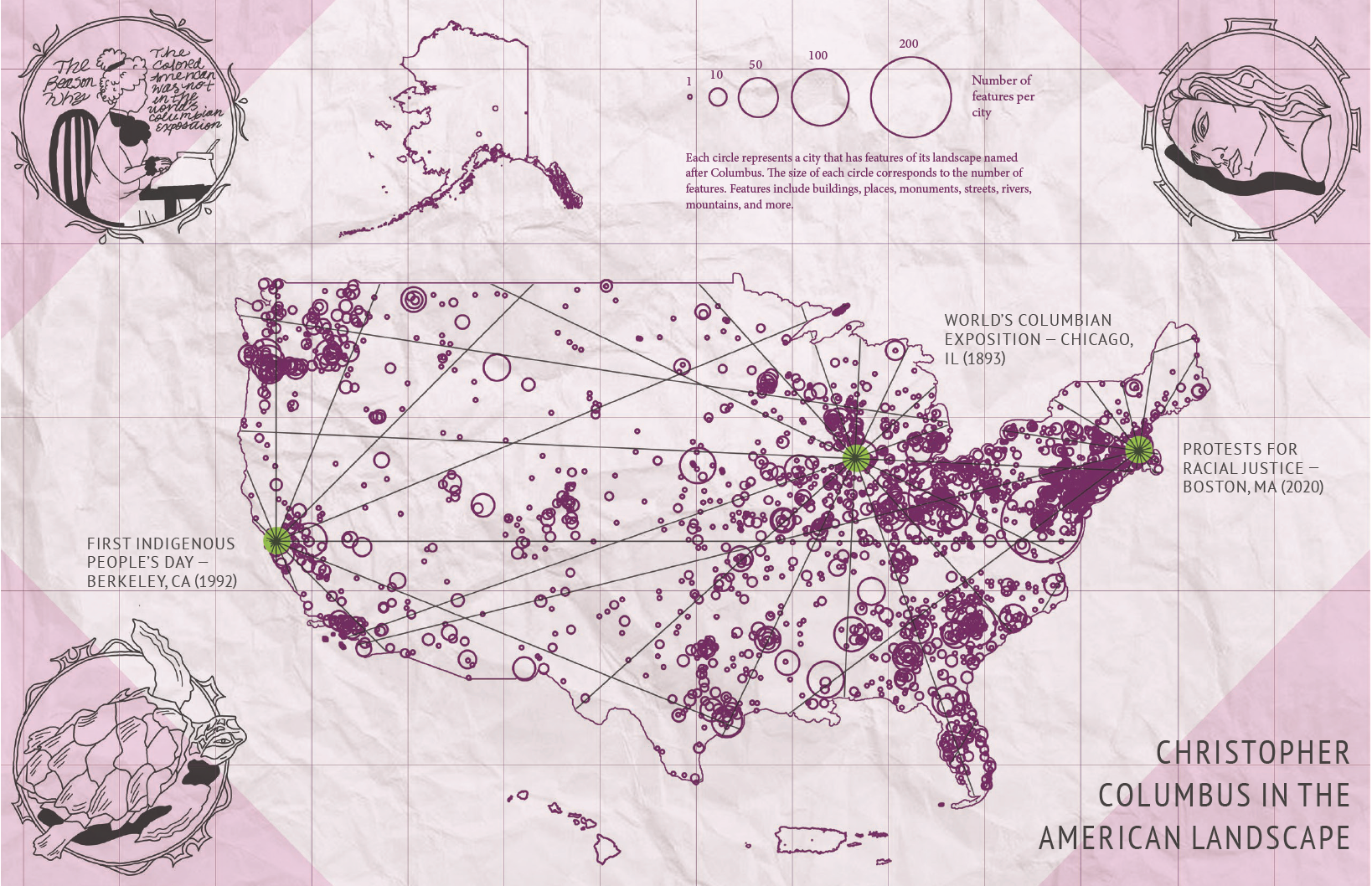

Did you know that there are over 6000 places in the U.S. named for Christopher Columbus? They include the nation's capital (District of Columbia), whole cities (Columbus, OH), rivers (the Columbia River), mountains (Columbus Mountain, CO), streets and monuments (Columbus Circle in Manhattan). How and why is Columbus so ubiquitous in the American landscape? Especially given that 1) He never set foot on the land currently known as the United States and 2) His prominent role in the nascent transatlantic slave trade and in the extermination of Indigenous people has been well-documented for more than 500 years.

These are the questions we began our project with. We are a group of researchers at the Data + Feminism Lab at MIT working on a project called "Audit the Streets" in which we are creating a large-scale public data portal with placenames and monuments connected to the historical figures for whom they are named. Columbus was immediately a curiosity because when you search for his name, the map fills with places that commemorate him – using either his full name, his last name or "Columbia", which was how early colonists feminized men's names when used to refer to land and territories (e.g. "America" following from Amerigo Vespucci). Few other historical figures are commemorated so widely, at such a national scale.

Student researchers and zine-creators Elizabeth Borneman, Hua Xi, and Lily Xie dug into the historical and academic literature around Columbus to try to better understand the history of his commemoration. They connected this to a long history of Columbianism which starts in 1697 when Massachusetts Chief Justice Samuel Sewell uses "Columbina" to denote the so-called "New World". This use gets reinforced and inserted into the landscape for the first time when colonists in the U.S. were seeking a non-British figure to build their new nation around, and named the capital city after him. Myths about Columbus as a heroic figure who "discovered" America started to circulate in the 1800s and by 1893, there was the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago dedicated to his legacy. According to scholar Thomas Schlereth, organizers drew on Columbus to shape four emerging aspects of American national identity: political identity, regional identity, military identity and diplomatic identity (Schlereth 1992). Around this time, he was adopted as a symbol for Catholic immigrants, especially Italian-Americans (like my own ancestors) who were facing persecution at the time. Civic organizations started to champion more Columbus streets, statues, plazas and schools (Paul 2014).

Yet the student researchers found something else that is little talked about in the history books. Counter-Columbianism also has a long legacy beginning with Columbus' own compatriot, Bartolomé de las Casas, who witnessed and wrote about the atrocities that Columbus and his men perpetuated on the Taino people, including massacres, infanticide, and enslavement. De las Casas spent his career as a friar petitioning all those who would listen about the grave injustices being perpetuated by Columbus in the "New World" (Clayton 2014).

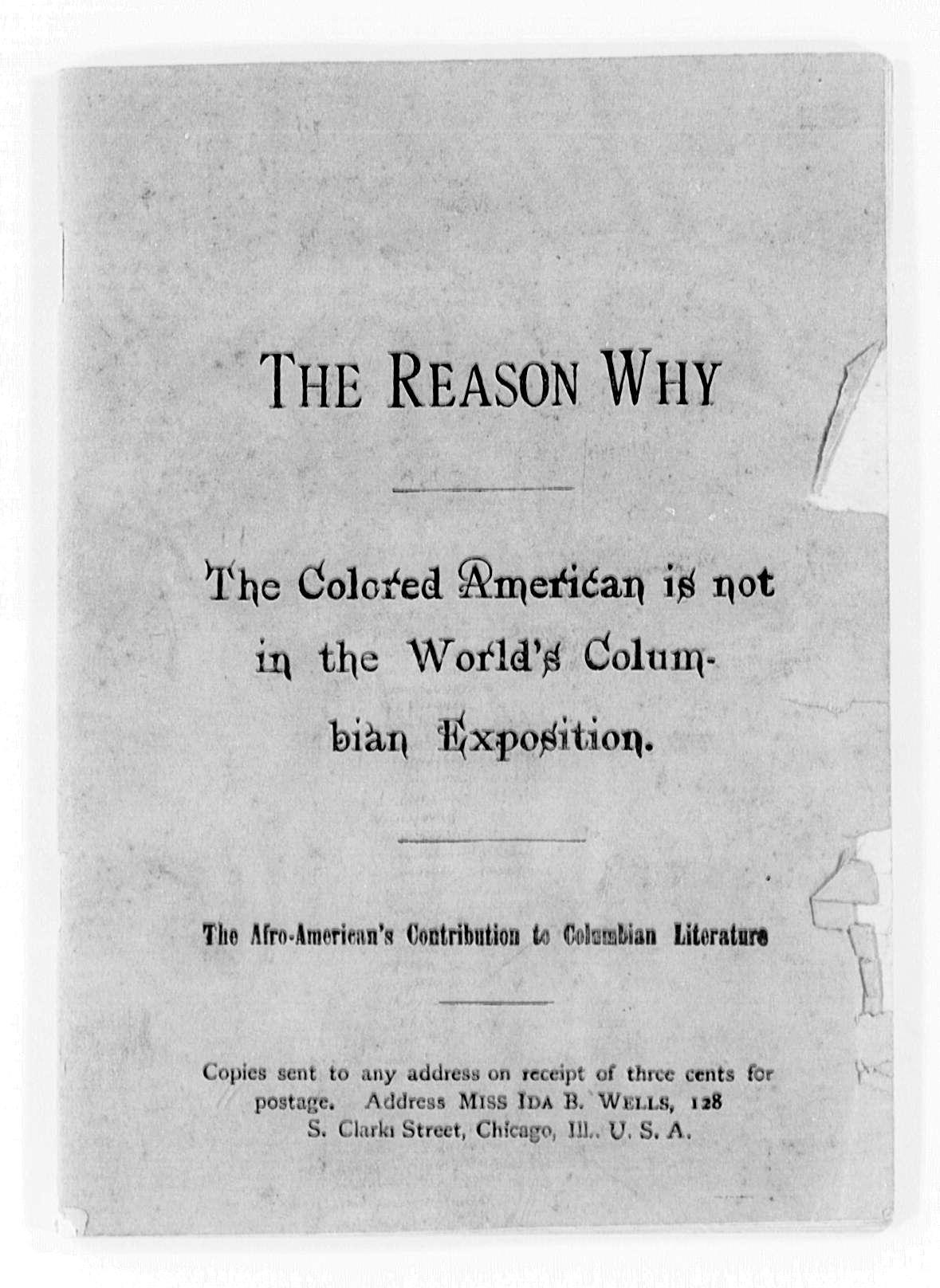

The students decided that the history of Counter-Columbianism was the story that needed telling, but how? Here they took inspiration from Ida B. Wells. In response to the exclusion of African Americans from the World's Columbian Exposition in 1893, Wells wrote and distributed 20,000 copies of the pamphlet in which she asks "Why are not the colored people, who constitute so large an element of the American population, and who have contributed so large a share to American greatness, more visibly present and better represented in this World's Exposition?"

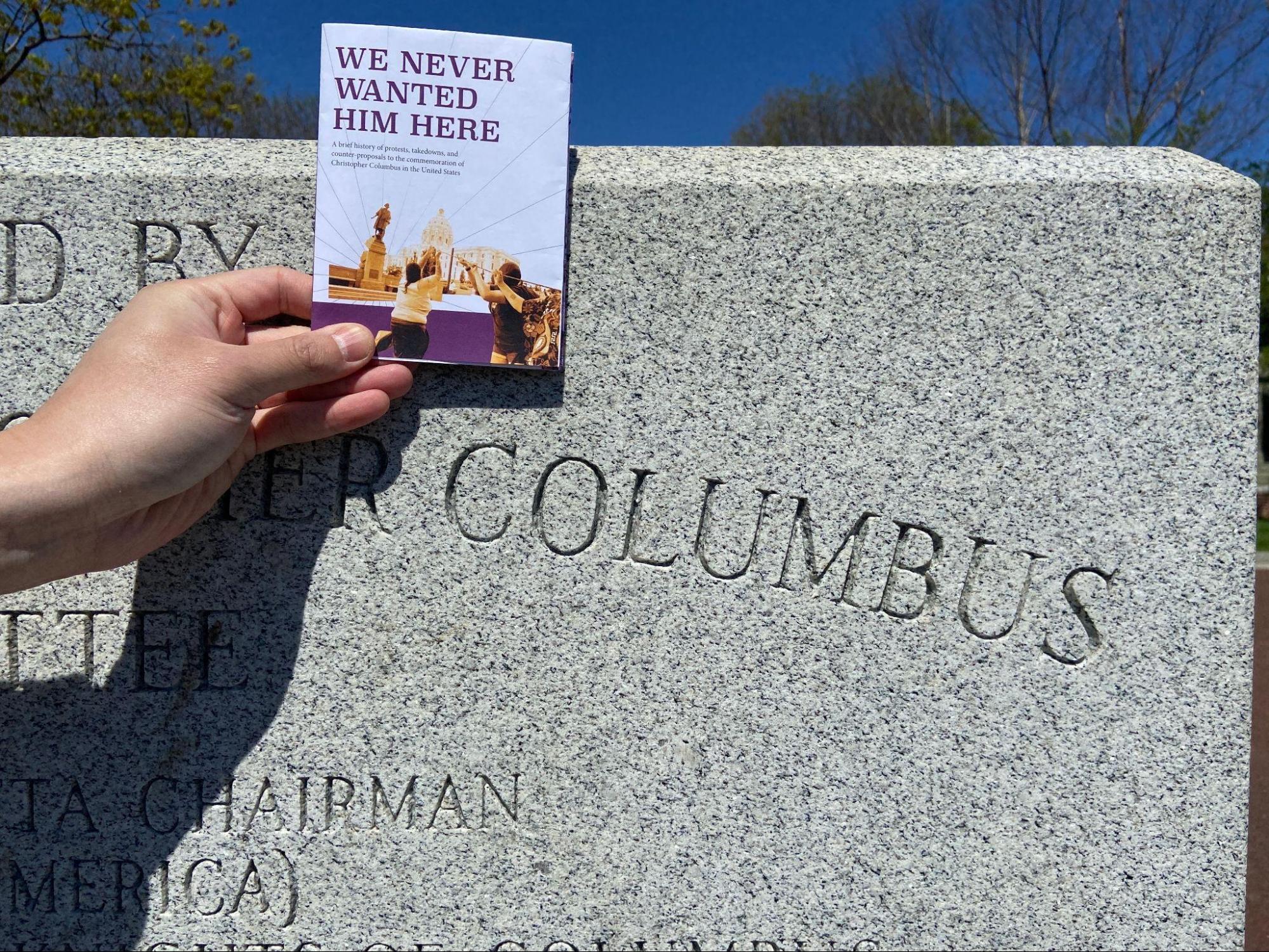

Building off the idea of pamphlets as affordable, accessible, and public ways to get a message out, the researchers created the zine "WE NEVER WANTED HIM HERE." It features the map (see figure 1) of all of the sites of Columbus commemoration in purple, and overlays notable sites of Counter-Columbianism on top in green. These include Wells's pamphlet; Indigenous resistance to the World Exposition; the movement since the 1970s to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous People's Day (Zotigh & Gokey 2020); and the work of Lee Sprague, Potawatomi and member of the Little River Bank of Ottawa Indians who designed the Turtle Island Monument for the City of Berkeley, CA.

The case studies in the zine culminate in the 2020 protests for racial justice, following which more than thirty-five Columbus monuments have been beheaded, behanded or officially removed by city governments. The case for Counter-Columbianism is growing, including by my own people – the Italian Americans – many of whom are pushing back against heroizing a perpetrator of so much violence and destruction. For example, in Massachusetts, the group Italian Americans for Indigenous People's Day is working in solidarity with Indigenous groups like the United American Indians of New England towards removing harmful symbols and holidays.

WE NEVER WANTED HIM HERE helps us understand the long-standing resistance to the harmful myths of Columbianism and invites us to imagine a landscape without Christopher Columbus. The zine and the Data + Feminism Lab’s larger project to “Audit the Streets” reflect our commitment to memory justice: auditing the unequal heritage landscape and uplifting histories that have been excluded, erased and contested in the process. Our statues and streets have never been static – they are dynamic and fluid sites for political education and transformation.

WE NEVER WANTED HIM HERE is a zine created by Elizabeth Borneman, Hua Xi, and Lily Xie as part of Audit the Streets, a project whose team includes Catherine D'Ignazio, Wonyoung So, and Nico Addae. All of us are researchers at the Data + Feminism Lab, based in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT. To get copies of the zine, please visit the website at: http://countercolumbus.dataplusfeminism.mit.edu

This essay in the “Changing Monument Landscape” series was commissioned as part of the launch for the National Monument Audit, produced by Monument Lab in partnership with The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. For more on the Audit, visit monumentab.com/audit.