Questions from the Archive

There has been much talk about the archive in academic and activist circles over the past decades. Who makes the archive? Who owns the archive? Where will the archive go, and who will have access to see the archive? The archive is a nebulous term that describes so much. Archives can be found in libraries, your browser history, museums, and any place where institutions play a role in constructing knowledge. The archive is knowledge. The archive can exist in multiple forms: from photos, films, folders, books, and sculptures. There are even archives of psychological traits and disorders. Because of technology there are more democratized spaces and forms of the archive from social media feeds and emails to the cameras on our phones. However, despite these advances in archiving technology, as individuals, we still do not have full autonomy. Our data is being archived to further our fall into the descent of mass consumption. As we are in a moment of hypervisibility of the archive, the ways that hegemony plays a role in the construction of knowledge is also that much more important to consider.

Monuments are archives. They are architectural objects that reinforce hegemony. They are the archive of a moment from the past. They are a reflection of the ways that a story from the past is told. In particular, the stories of the past that reify hegemony. In this way, monuments can be viewed as archives of hegemony.

Monuments are objects of memory, of remembrance. To put it another way, they are rememory objects.These objects are a reflection of the culture and of the time in which they were built and the times that they remain to be revered. These objects are an integral component to the creation of the cannon of history. These objects are steeped in the packaged mythology of a society. It is clear that the mythology and material reality of this society is seeped in white supremacy - it is why so many monuments are white and male. Of course, there are always exceptions.

An Archive of an Archive

In The Reorder of Things Roderick Ferguson illustrates the way that the construction of knowledge in the University system is an archival project.

“As such, the academy is an archive of sorts, whose technologies— or so the theory goes—are constantly refined to acquire the latest innovation. As an archiving institution, the academy is—to use Derrida’s description of the archive—“ institutive and conservative. Revolutionary and traditional.” In order for any institutional archival praxis to stay on the cutting edge, it has to be progressively moving forward, and at the forefront of knowledge. But the contradictions that exist in a progressive institutional project continue to be seen and experienced by the individuals who work in institutions seeking to move the institute towards progressive change. There is an ongoing tension, a push and pull that seems constant and inevitable.

In the context of my creative praxis that troubles monuments, I am thinking about monuments as Ferguson considers the University. Monuments are an archival project “whose technologies... acquire the latest innovation” that can have contradictory purposes and be both “revolutionary and traditional.”

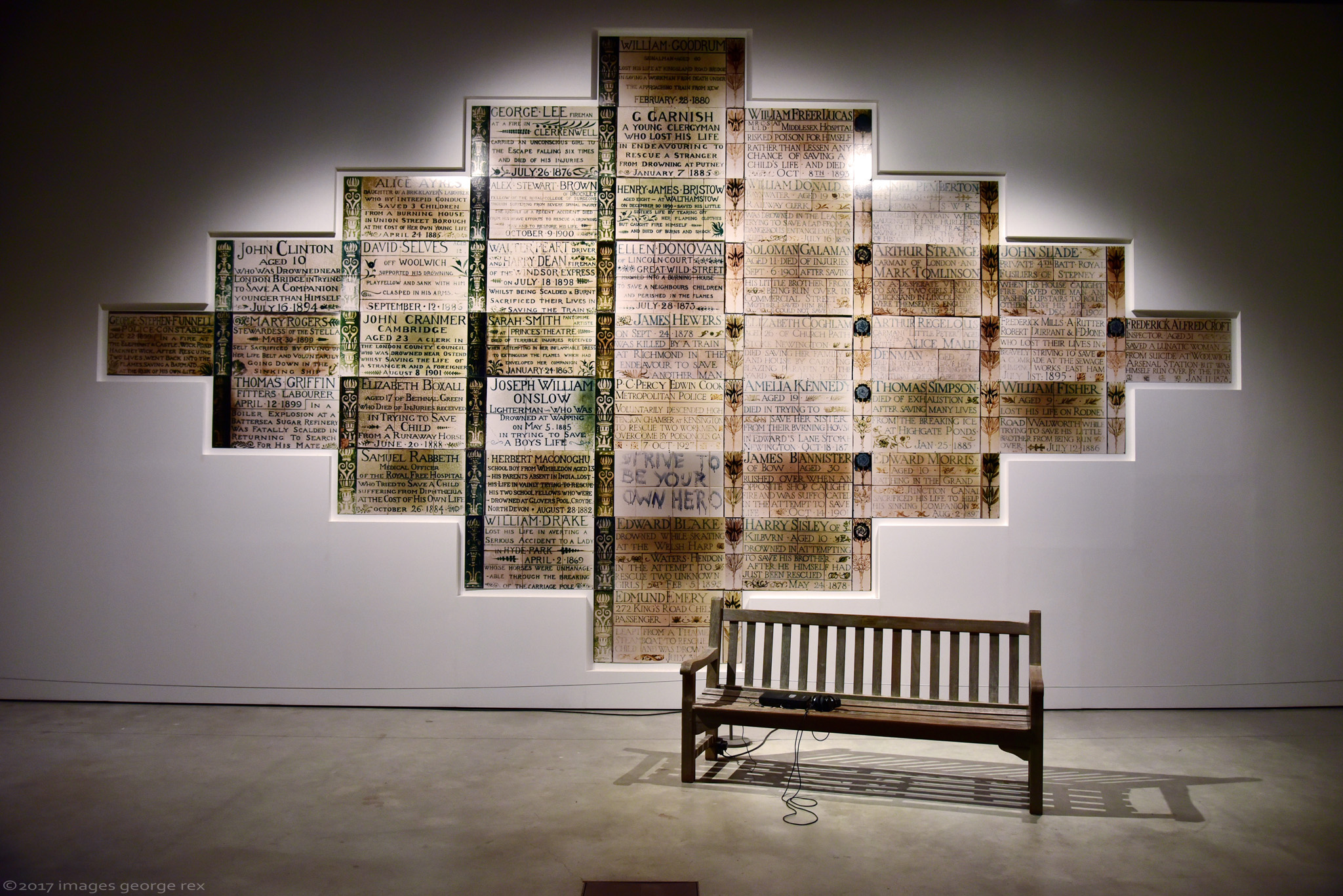

Susan Hiller’s 1980 installation Monument queries a personal response to the monument as an archive. The Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice is an archive of individual people who performed an act of heroism. The work was proposed in 1887 by George Frederic Watts. His initial proposal was rejected but he was approached eleven years later by a vicar of the church of St Botolph's Aldersgate. It was thought that Postman’s Park would raise the profile of the site and could be used as a fundraising tool. (Here is an example of how “creative placemaking is not a new strategy.” In other words, the exploitation of innovative designs by artists to serve the interest of hegemony and capitalist interests is not a new praxis, but I will save that deconstruction for another essay.)

The narratives of the people who are ignored by the historical cannon, or the archive of history textbooks are further placed on plaques. The number of plaques are a reflection of how old Hiller was at the time this installation was made. Through this process, her mortality is connected to the mortality of the people who are commemorated in the plaques. And it is for this reason, that this work is an archive of an archive. The everyday perspectives on monuments is the goal of my LandMarked Project. Through this work, I aim to create an archive of the everyday experience with the form and function of the monument.