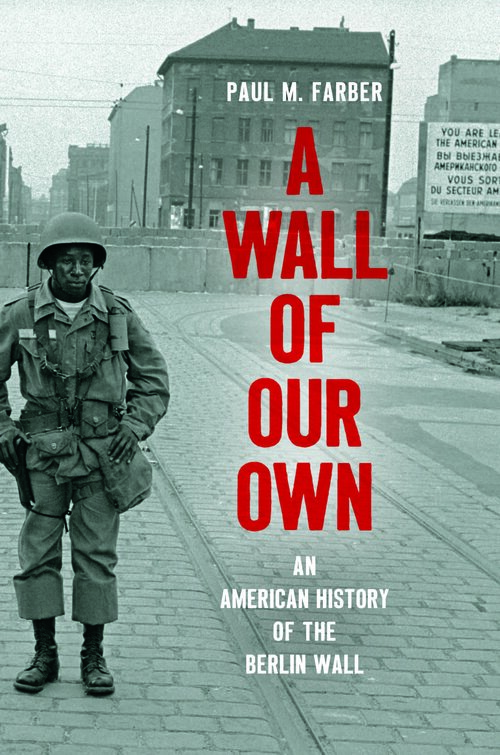

Cover image: Leonard Freed, Berlin, 1961 (Estate of Leonard Freed/Magnum Photos).

A Wall of Our Own: An American History of the Berlin Wall by Paul M. Farber. Copyright © 2020 by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by permission of the publisher. www.uncpress.org.

The story of America’s relationship and identification with the Berlin Wall has previously been told through decades of public history, popular culture, and political discourse celebrating the so-called fall of the Wall. A large and still-growing body of historical literature and cultural works references the Berlin Wall in an attempt to make sense of America’s role in the Cold War, from its early years through its demise to its afterlife today.

Such narratives of the Berlin Wall within sites of public interpretation and expression often work through the landmarks of presidential visits and military operations, treating cultural expressions as necessary only for background soundtracks and illustrations or as endearing oddities to animate a teleological story from rise to fall. President Kennedy’s refrains of symbolic citizenship in 1963 (“Ich Bin ein Berliner” and “Let them come to Berlin”) and President Reagan’s bold plea in 1987 (“Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall”) reverberate as dramatic moments of American rhetoric at two opposing ends of this timeline, without much attention to what narratives they obscure and in what ways they are extensively mythologized, parodied, critiqued, and remixed. In other words, they obscure how the lessons from the dismantled Berlin Wall inform and haunt American public discourse on our own walls.

The American fascination with the Wall did not fade after the initial shock of construction in 1961 or during the decades of simmering coexistence or with the dismantling of the Wall in 1989. In fact, over time, the Berlin Wall has become even more embedded within the landscape and discourses of U.S. geopolitics. Hundreds of cultural references express intrigue in Berlin’s divided status. Rarer are works that consider the way the story of the Wall has been incorporated into our U.S. national narrative and for what purposes. For example, a broken piece of the former Berlin Wall from the collection of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., was included in The Smithsonian’s History of America in 101 Objects with an annotation qualifying it only by its existence as a fragment (“This one has special meaning precisely because it is broken!”), rather than as an outlier in this quintessential collection of “Americana.”[ref]Richard Kurin, Smithsonian’s History of America, 500–505.[ref] Much of our public history related to the Berlin Wall often recounts America’s relationship to the Wall in similar fashion, across dozens of prominent sites, supplemented by fields of documentary film and television, museum and library exhibitions, commercials and advertisements, online wikis and memes, and other references to the Wall across cultural formats, often portraying the Wall as a self-apparent symbol of progress without room for critical analysis of its inclusion, let alone comparing our own border controls and networks of divided power.

In addition, video montages and interpretations of historical time lines—especially those used in television commercials for Pepsi and Johnnie Walker, among others; aired during key sporting events, such as the Super Bowl or the World Cup; or placed in museums such as the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., or the Constitution Center in Philadelphia—often include footage of the Berlin Wall’s dismantling to illustrate one sequence in a flow of events that embody a milestone or endpoint to celebrate the progress of U.S. “history.” In such productions, the taking down of the Wall slips into the narrative alongside critical markers in American history. Such representations seem to be stuck in a feedback loop that favors the experience of elation rather than historical reflection, a fantasy of freedom that smooths out complication. As Joshua Clover notes, “It is impossible to ignore the extent to which the Berlin Wall’s deconstruction, as captured in photos, broadcasts, videos, news reports, and the rest, provides a concrete image of unification as an achieved condition, of the overcoming of contradiction and discontinuity.”[ref]Joshua Clover, 1989, 13.[ref] In mainstream venues, the Berlin Wall slips in and out of perception and in and out of an Americanized, imagined geography.

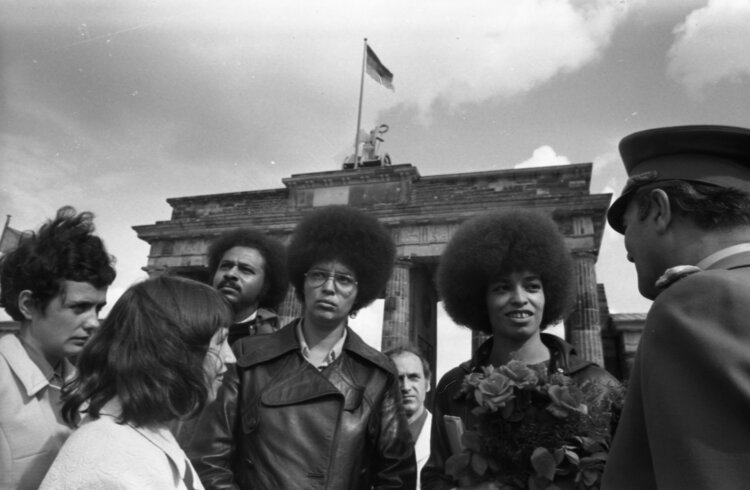

Peter Koard, “Davis, Angela, East Berlin: Visits East German Border with West Berlin,” September 1972 (BArch, Bild 183-L0911-030).

Beyond the hundreds of references to the Wall in popular and political culture while it was standing, again, one can look to the dozens of pieces of the former Wall that have been placed in dozens of monumental contexts and public spaces across the United States since reunification as proof of this long-standing incorporation. Such remnants—whether they are installed in the galleries of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.; along Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles; across numerous presidential libraries and college campuses; on a public plaza adjacent to Ground Zero in lower Manhattan; or at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center along the Ohio River, which once represented the demarcation line between free and enslaving states—speak to America’s deep bonds with Berlin. In some instances, the Wall fragments celebrate state-sponsored diplomatic relationships between the United States and reunified Germany; in others, they are self-evident “pieces of history” to reflect narratives of U.S. power and progress; and finally, in rarer cases, their placement refers to the layers and legacies of domestic division as inscribed into our public spaces during this same period.[ref]For more on the pieces of the Berlin Wall installed around the United States and associations with Cold War memory, see Jon Wiener, How We Forgot the Cold War.[ref] To gain a fuller understanding of the American history of the Wall, one must explore and read across the scores of cultural identifications the Wall’s interconnected narratives of liberty and restraint. Such an exploration places cultural production in relation to politics not as an oddity or an afterthought but instead as forms of expressive diplomacy, resistance, and contestation of state narratives. Taking this approach permits a deeper consideration of the complexity of U.S. geopolitics and the imposed limits of freedom. Our walls—past and present, as well as under construction and in contention—directly challenge the notion of a historically indivisible nation. Americans’ ongoing attachment to the story of the Berlin Wall as a site of triumph connected to American democracy, or as a litmus test for how divisive our internal and external borders can be, is fueled by more than a generation of creative agents who reflected on the Wall and other dividing lines as persistent structures in the American culture. […]

Shinkichi Tajiri, The Berlin Wall, 1969–1970 (Shinkichi Tajiri Estate).

A Wall of Our Own proposes a renewed call to collectively explore the work of American artists, writers, and activists in Berlin during the Cold War—in part, to make sense of the continued practice of identification with the Wall and other geopolitical discourses that remain vitally connected to Berlin. While an American presence in divided Berlin was originally personified through extensive military deployment and prominent political appearances along this volatile zone, American artists and writers mapped, read, and expanded significant aspects of Daum’s notion of “America’s Berlin,” as a place of democratic longing and experimentation. Berlin continues to be a place where we reckon not only with German history but with American practices of democracy and repression, too. Each chapter of this book explores American cultural productions that were routed historically and conceptually through a divided Berlin. The chapters detail representations of the Berlin Wall and catalog the creative processes that led toward the production of a particular book about U.S. cultures of division and solidarity. Considerations of published works are interanimated with reflections gleaned from archives, encompassing materials from library collections, national holdings, oral histories, and private papers. The various Berlin Wall books exist in distinct genre forms—the photobook, the political autobiography, the conceptual art book, and the poetry collection—but overlap in their methods of production and patterns of critical discovery, whether produced inside or outside Berlin. While disciplinary readings in fields of cultural history, literary studies, or art history allow particular claims to be made within a given chapter, my project aims to “form an archive,” as Andrew Friedman puts it in another context, “that arises from a landscape rather than a discipline.”[ref]Andrew Friedman, Covert Capital, 14.[ref] Out of the archive of American Berliners’ engagement with the border zones and occupied sectors surrounding the Wall, the cultural productions examined in these pages constitute a critical constellation of work made by Americans whose encounters in a walled Berlin led to projects directed at other sites of division.

Dagmar Schultz, “Audre Lorde at the Berlin Wall in 1990” (Dagmar Schultz/Third World Newsreel).

By focusing on the individuals within networks of artistic and political engagement, this book demonstrates that the Berlin Wall reflected significant histories of social division beyond scripts of state authority and military strategy. U.S. artists, writers, and activists working in and through Berlin approached boundaries of freedom through a practice that Salamishah Tillet terms “critical patriotism” engaging sites of freedom and repression in a manner that “neither encourages idolatry to the nation’s past nor blind loyalty to the state” but through “dissidence and dissent . . . re-engages the meta-discourse of American democracy.”[ref]Salamishah Tillet, Sites of Slavery, 11.[ref]

The American Berliners at the center of this book are intriguing not only for what they explored and created while the Wall stood; each returned to Berlin after its dismantling in 1989. Through their returns, they spark and extend historical questions through practices of cultural memory while back in then-reunified Berlin. Their work on the Berlin Wall builds on previous themes but remains an incomplete task; as they find productive points of reflection, they strategically avoid closure on matters of history and democracy.

Together, through historical engagement with the period of the Berlin Wall and excursions through its monumental afterlife, the on-site explorations of the divided city and the Berlin Wall by Freed, Davis, Tajiri, and Lorde prompted reflections then, as they do now, on the complexities and fault lines of America’s democratic project. Such reflections grappled with Cold War policies and practices and, when read today, continue to spark engagement with American global politics and the shared physical and symbolic character of border walls, as a matter of navigating our own political landscapes of division. Rather than seeking Berlin as a site in which freedom and repression are to be imagined as distinct formations, historically or geographically, the reader is invited to approach the city as a means of understanding the dialectical relationship between freedom and repression as interlinked. In other words, this book aims to unseat the relative ease with which American culture currently incorporates the Berlin Wall into its own history of progress without further reflection on our own lines of division—whether physically or socially inscribed, historically relevant, or newly emergent since 1989. My hope is to spotlight the enduring and urgent role of the artist, writer, or activist as a civic actor. Cultural agents meaningfully task themselves and the rest of us with weighing American practices of freedom, moving in and out of U.S. borders and internal sites of division, critically exploring zones of conflict, and mapping the gaps between the nation’s democratic ideals and lived realities.

The Berlin Wall emerged as a site integral to and symbolic of the Cold War cultural imagination in the United States, but only in retrospect can we discern how integral the stories of struggle by the Wall are intertwined both with those of its triumphant dismantling and with our current failures to imagine a world without pernicious lines of division. The Berlin Wall continues to signify on this cyclical history, especially as leaders and state actors—responsible for the fortifications and inhumane detention policies along the U.S.-Mexico border, the apartheid walls separating Israel from Palestine, the fences built to hinder refugees crossing into southern countries of the European Union, and the sites of climate and ecological violence, among countless other barriers—fail to learn crucial lessons from the profound violence and ignorance of bygone wall builders. The chants to “build the wall” on the U.S.-Mexico border are echoes of deep-seated white supremacist fantasies in the United States that have countered freedom principles throughout the nation’s history. Berlin continues as a point of reckoning and return, once again, to measure those principles against our own practices of repression, to grapple with the weight of history and dreams of transcendence.

In the spirit of critical reflection, A Wall of Our Own attempts to gather the many disparate accounts of American artists beckoned to divided Berlin into a shared historical frame. This book also is meant to serve as a roadmap of creative process, moving in and out of divided Berlin, through other geopolitical sites of division, toward critical engagement and awakening. The path follows a critical and curious stance to life along our borders.