A circle of red bricks in a herringbone pattern now grace the spot on the campus of the University of Mississippi once reserved for a 30-foot memorial to the Confederacy. The brass contextualization plaque for the statue is also gone, one reminding those who may have stopped to read that “this historic statue is a reminder of the university’s divisive past,” given the statue’s enshrinement of the ideas of the Lost Cause and White supremacy. In spite of this change, vestiges of Confederate commemoration remain on campus. For example, nestled inside the gothic turrets of Ventress Hall is a gleaming Tiffany stained-glass window from 1891. The window is dedicated to the University Greys, a Confederate regiment made up entirely of students from the University of Mississippi. Today, the statue now stands in the cemetery that contains the remains of the University Greys—an appropriate site for a statue that is a memorial to the dead.

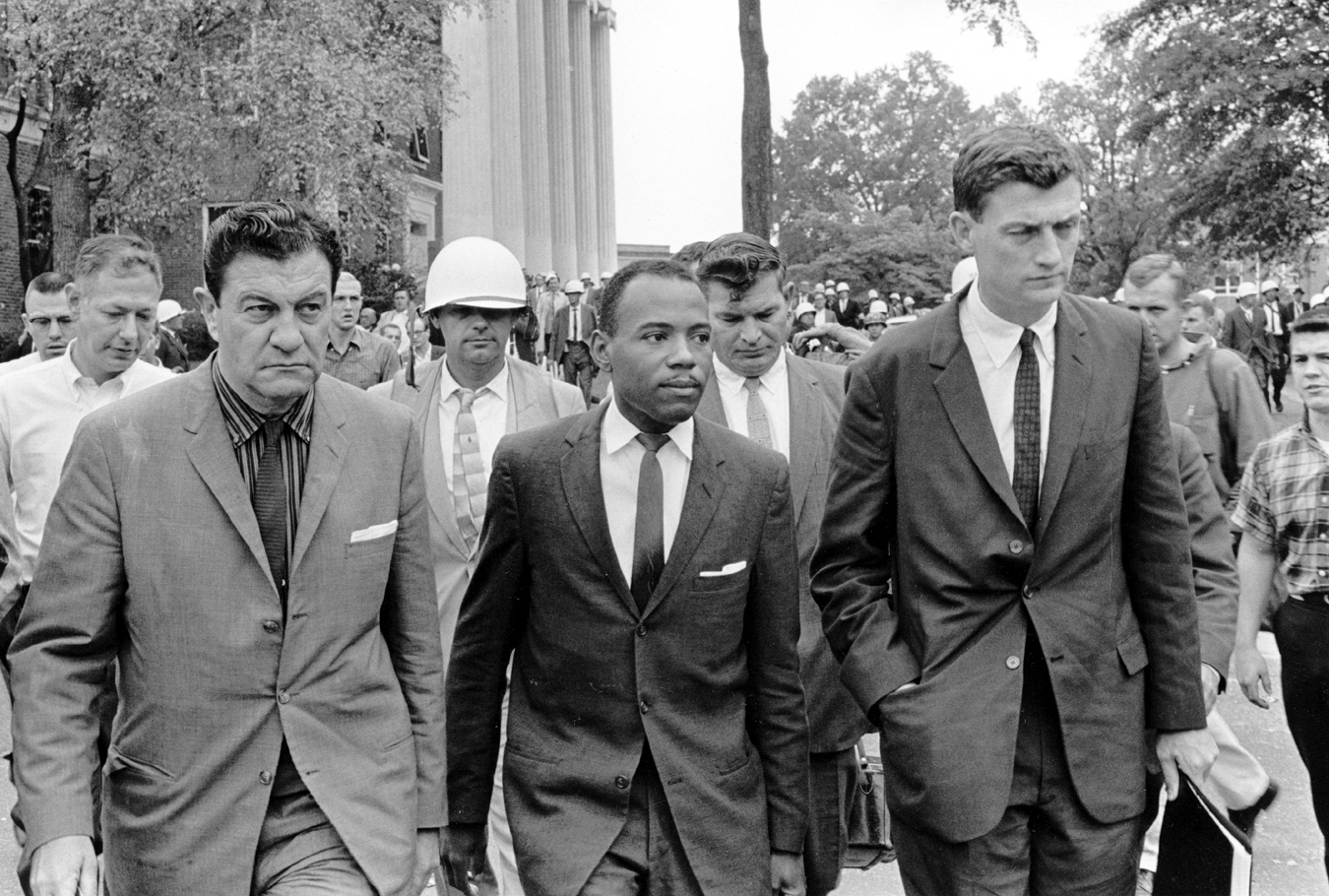

For decades, the University of Mississippi has distanced itself from Confederate symbols, in spite of the desire of many alumni to maintain the campus as a memorial to the Lost Cause. The university was the first in the state to stop flying the old state flag, which included a Confederate battle flag in its design. Now, with the removal of the Confederate statue from the center of campus, the university is outwardly free of Confederate symbols. Most important, a Confederate statue is no longer the first thing a visitor sees when visiting the grounds. Instead, visitors are greeted by a memorial to James Meredith, the man who racially integrated the university in 1962 as its first African American student. Following a lengthy courth battle, the Kennedy administration ordered 500 U.S. Marshalls to Mississippi to ensure Meredith's safety as he arrived on campus. After two days of rioting by those opposed to Meredith’s admission, 2 people were dead and around 200 people were injured as a result of the violence. The great irony is that the very statue that served as the rallying point for the rioters is now gone, yet the statue to James Meredith remains.

The statue shows Meredith walking through the doors of the university, which are engraved with the words, “courage, knowledge, opportunity and perseverance.” These words tell a story of civil rights triumph—particularly Meredith’s defiance of Mississippi segregationists. Yet they only tell one story connected with the integration of the University of Mississippi.

After Meredith, the Struggle Continues

When we think of the risks African Americans took to integrate places like “Ole Miss,” we tend to focus on the “firsts.” And, we often memorialize those firsts and overlook those who came after them and continued the work of those who broke barriers. There is also a tendency to place tumultuous events related to civil rights in the 1960s in a separate and sacred sphere, forgetting that it was not until the 1970s that African American students at recently integrated universities began to demand that their voices be heard. Even a decade after integration, Black students felt that their presence on campus was just tolerated, that they had no voice, and in some ways were looked upon as intruders. As someone who was an undergraduate at the university in the mid-1970s, I would say that to be a Black person at the University of Mississippi was to be both invisible and conspicuously present. It was not until January 1970 that Mississippi’s schools were fully integrated, and pushing past that last barrier of segregation created an environment where Black people felt they could no longer be silent. Meredith may have opened the door, but there was still work to be done.

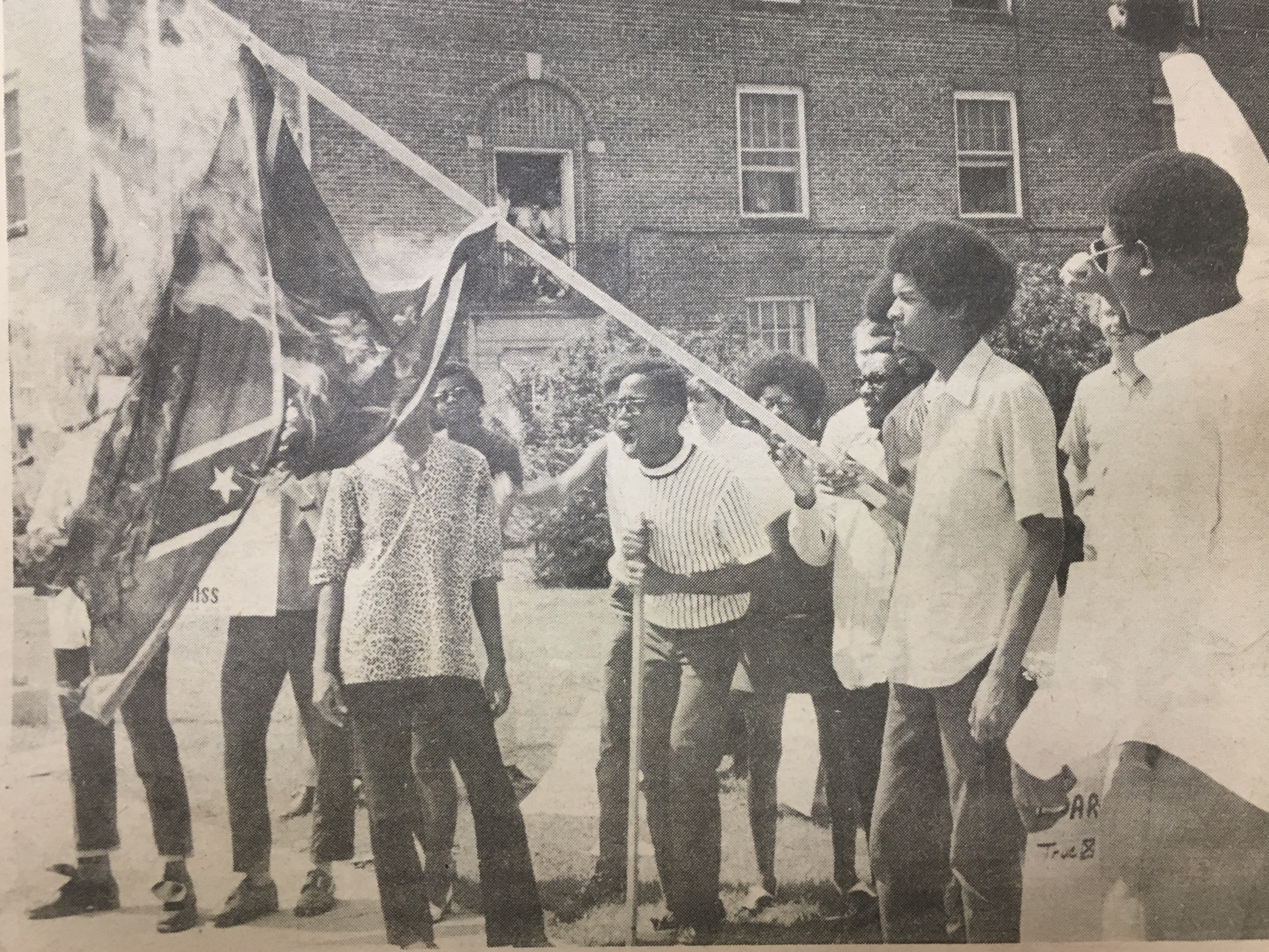

That is why just eight years after Meredith’s arrival, on the evening of February 25, 1970, a performance of the clean-cut and upbeat traveling musical ensemble Up With People (a group known for performing songs with anodyne titles like “What Color is God’s Skin?”) began in Fulton Chapel at the University of Mississippi. This group of joyous cultural ambassadors was not anticipating that they would be joined on stage by a group of 40 Black Ole Miss students giving Black Power salutes. The black-glove-wearing students were seeking attention for the list of demands being ignored by the university administration, even after burning a Confederate flag in protest in front of the student union building just a few weeks before. Protesting at a high-profile event that would include university administration officials in the audience seemed like a good strategy for achieving their goal. Instead of the desired result, all of the students that evening—as well as 30 others in an associated protest at another location—were arrested, some at the Oxford-Lafayette County jail.

When the county jail ran out of room for prisoners, 40 of the young women and men were sent to the notorious Parchman Farm State Prison in the Delta. A total of 89 students would be arrested and eight of the students from the protest would be expelled from the university, originally on charges of illegal trespassing. Another45 would be expelled on the same basis but given suspended sentences after disciplinary hearings that took on the tone of an inquisition. Had the Department of Justice not intervened, the trespassing charges would not have been dropped and disciplinary hearings would never have been held.

Memorialization to Heal the Wounds of Silence

The story of Ole Miss’s Black Power protest is one that has been suppressed by the university, in spite of its message of persistence that carries on Meredith's legacy. The protest is also connected with other tumultuous historic events in 1970. In the same month as the Ole Miss protest, a group of 894 students from the nearby Mississippi Valley State College had been jailed at Parchman for protesting their campus living conditions and the quality of instruction at the college; the New York Times called this roundup “the greatest mass arrest ever conducted on an American campus." Then, on May 15, 1970, after a false claim asserting that a sniper had shot at them from a window in Alexander Hall, Jackson, Mississippi police fired more than 400 rounds of ammunition over 28 seconds in every direction on the campus of Jackson State College, killing two undergraduates. Jackson State may have been an historically Black college, but like their counterparts at the University of Mississippi, the students’ recent activism had been informed by the Black Power movement and was perceived as a threat in a state still dominated by White supremacists.

In a state that persists in proclaiming April as Confederate Heritage Month, the struggle against anti-blackness is ongoing. More than fifty years later, at the University of Mississippi we are beginning to see how the protests of 1970 on our campus are connected to those at two other Mississippi universities. Then, soon after the 50th anniversary of these protests, Mississippi changed its state flag. The story of the Mississippi state flag provides a window into how false narratives about history—particularly in the American South—are sustained. The changes at the University of Mississippi, as well as changes to the state flag, led to questions about whether the university is telling a full historical story of protests on our campus. More important, these changes present an opportunity for the state and the university to build and promulgate a new cultural narrative, one rooted in truth rather than deception about the past.

At the University of Mississippi, a faculty task force charged with historical documentation of the 1970 protests is beginning to discuss how we can create a new cultural narrative through memorialization. This task force is working in tandem with the former students who were affected by the events of 1970. Through the oral histories we have collected from former students and members of Up With People as well as listening sessions we have conducted with the former students, we have concluded that we are not just seeking to simply commemorate an event in our campus’s history. What we need is a memorial that shows how historical events on our campus are also connected to similar occurrences on other campuses in our state. Through a series of connected memorials on each of the campuses, our hope is that we can enlarge the narrative of civil rights in Mississippi as well as that story’s connection to the struggle for human rights around the world. After fifty years of silence, it is time.