What do you do when you’re fighting for survival and balancing grief on a societal level at the same time? This is a question many of us are facing now and asking ourselves in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

One of the historical reference points we can access are stories from the 1918 Flu Epidemic. Dubbed the Spanish Flu, the deadly pandemic killed at least 50 million people worldwide, including a half a million in the United States. These numbers can sound abstract, or worse, like cold statistics. It is hard to fathom such loss.

We also know that the 1918 pandemic coincided with World War I and deeply impacted military operations worldwide. More American troops died from the virus than in combat. But there are few monuments and memorials to victims of the Pandemic in the United States. No statue, no historical marker even in Philadelphia, one of the hardest hit cities in the U.S., where 20,000 people died of the Flu. This includes my great-great-grandmother.

Our guest on this episode, Nancy Hill, one of the Philadelphia-based organizers of the Mütter Museum’s exhibition on the 1918 pandemic, Spit Spreads Death. She shares insights with us about how the pandemic is and is not remembered.

“People could either choose to celebrate the armistice or they could choose to grieve not only the flu dead, but the military dead, the war dead. And they chose to celebrate the armistice instead and try to move on with their lives because it was just too much. And hopefully, we've gotten enough distance from this that we can start to commemorate those people because their families are still talking about them today, there are experiences that they survived and that they remembered have shaped their family for generations whether or not they knew it at the time.”

This episode, we speak to Hill about cultural memory and timely lessons from the 1918 pandemic. The parallels between then and now are astounding, informative, and troubling.

She shares stories of vulnerable communities – immigrants, African American migrants – who were hard hit by the virus and society’s response. She also unpacks how the ways everyday residents stepped up to help one another to care and commemorate in urgent ways. She also helped me shed light on my great great grandmother’s story, how she and her community may have experienced the 1918 pandemic.

Hill closes with her hopes for greater understanding about viruses, and science behind them, as ways we can cope and look ahead.

Paul Farber: Nancy Hill, welcome to the Monument Lab Podcast.

Nancy Hill: Thank you so much.

Farber: Thank you for being here. To begin, we're in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, and there's often reference to the 1918 flu pandemic. For our listeners, could you give a brief overview of what that pandemic was, and the history that would be helpful for us to know in the present?

Hill: Sure. So in 1918, specifically in the fall of 1918, a pandemic swept the entire globe then hit some certain locations particularly hard. It was an influenza pandemic, specifically an H1N1 strain, similar to the swine flu of 2009. It's not known exactly where it originated, but it's hypothesized that it either began at a military training camp in Kansas or potentially in China. However, this was the first really global pandemic because this was going on at the same time as the World War I. And so it erupted it at a time where unusually there was global travel in a large mass rather than previously contained ocean liner travel that took weeks and weeks.

So this pandemic ended up killing an estimated 20 to 50 million people worldwide. Those numbers are highly contested because of record keeping being not what it is today. Philadelphia was a particularly hard-hit city with about 17,500 deaths documented for the six months starting in September of 1918 until February of 1919. And this really had a major influence, not only on the United States and Philadelphia, but also on the outcomes of World War I, potentially on Indian independence in South Asia. This was really a massive event that due to shared collective trauma and political timing, has not been talked about much.

Farber: I want to follow up there, can you share a little bit more about how the flu pandemic may have shaped the World War I conflict and Indian independence in Southeast Asia?

Hill: During World War I, more soldiers actually died from pandemic flu than actually were killed in combat. And this war was horrifying in an unprecedented way for the time, and even for now, I mean, this was the debut of gas warfare. We're talking about trench warfare where infection environments were very... The environment was not healthy for soldiers, it was not healthy mentally or physically, there were a lot of infections going around, gas warfare, the kind of traditional traumatic injuries that you think about as well as this viral pandemic that affected both sides of the conflict. However, neither side really published about it, part of why we call this colloquially the "Spanish Flu" is there were censors on both presses, on both sides of the conflict and neither side wanted to let the other know that they were compromised.

And so you never saw front page news about this pandemic except in Spain, which has part of why it's known as the Spanish flu. And so because of the high number of fatalities of troops and ultimately political leaders as well. This was something that was quietly and secretly ravaging both the military and political figures. And it is hypothesized, again, it's hard to point to this directly as a contributing factor, but Britain obviously was very involved in the military conflict and crippled by the pandemic flu.

And when you're trying to maintain control of a colonial territory and you've just dealt with a massive military conflict and you're also still dealing with this pandemic at home that has cost a number of lives, it's depleted a lot of resources, it's going to become a lot harder to maintain control of that colonial territory. It's hard to point to specifically the flu as the straw that broke the camel's back, but it certainly depleted resources, both financially and personnel wise, politically to maintain control over a remote territory like that.

Farber: Did that play out in other places of colonial occupation and rule?

Hill: It's hard to say specifically. I think India is the one that I have seen the most discussion about because again, timing wise in the following decades the flu pandemic was happening right at the same time as these independence efforts on behalf of Indian nationals. There's been a lot of speculation about the role that the pandemic could have had in women's suffrage, again, where a lot of things happened right after World War I, and it's hard to say concretely what was because of the pandemic and what was because of the war. A lot of these events undoubtedly both contributed in their own right. But when you think about women's suffrage and prohibition and the kind of trauma that people were dealing with after this, I'm sure there were a number of social woes that people were seeing unfold in front of them and wanting to address due to that trauma.

Farber: In 2020, we're watching a modern medical system stretched to its capacity— is brought to its knees. How did medical facilities fare in 1918? How did they handle the pandemic then?

Hill: Well, I will say that medicine in 1918 was extremely different than it is now in a number of fronts. Today, we're obviously dealing with personnel shortages and equipment shortages, things like ventilators. In 1918, there was no ventilator, there was no antibiotic to fight secondary infections. The flu is a viral infection, but it does open you up to things like pneumonia, which is a bacterial infection. So in 1918, the really only options were to monitor fever and try to manage those symptoms as best you could. However, again, here's where World War I becomes a big kicker, especially in Philadelphia, we were missing a lot of our medical force domestically because they were away with the military.

And so when this pandemic came to Philly, there was a shortage of medical professionals at Pennsylvania Hospital, and they had about 25% staff. Other places had closer to 75%, but still, you're fighting this fight with one arm tied behind your back

Farber: Your project, Spit Spreads Death is focused on Philadelphia. What about the city is important to understand the 1918 pandemic?

Hill: Well, I think it's important to A) highlight Philadelphia was one of the worst-hit major cities in the United States. This is contested between Philly and Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh had a higher number of deaths per capita, but their population was quite a lot smaller and so it's kind of a statistic interpretation issue. But Philadelphia at the time was really this industrial powerhouse and you had Center City still had a lot of these beautiful hotels, a lot of which are still there today, a lot of those buildings are still there today. Running water, streetlights, all of that.

But South Philadelphia and other residential neighborhoods in the city homes didn't have running water yet, and so there was a massive disparity of access to technology and access to resources in the community. And so Philadelphia has a good cross section of being an urban environment, having a lot of different types of people present, having a lot of different types of resources distributed in a way that may or may not make sense, and I think the pandemic shed light on that in a lot of ways. And then it also just again, it signified and represented a lot of the things that United States was proud of at that time. All of these huge factories, shipping ports, lots of employment opportunity in the area, and very much was brought to its knees by this.

Farber: The COVID-19 pandemic has turned many of us into armchair epidemiologists. We're reading news reports as they come, the announcements from a variety of federal and state levels, trying to make sense of how best to protect ourselves and our communities. Spit Spreads Death was a rallying cry in 1918. Who coined it and how did it circulate in the public health realm?

Hill: So the name Spit Spreads Death actually comes from the public health campaign to prevent the spread of influenza in 1918. And so we got the name of the exhibit in particular from an image of a poster. There were, again, these posters all over the city. Posters were very much a thing in 1918 with the war going on, a lot of political propaganda and things like that. And so our historical curators and the artists at Blast Theory that we were working with were struck by a particular image that we found of a Fourth Liberty Bond Campaign sign, it's a wood sign on a lamppost, and slapped up over that is a paper sign that says Spit Spreads Death. And that was the public health messaging at the time to try and slow the spread of pandemic influenza.

So we got that name directly from the public health messaging at the time. Other signs that you would have seen relating to the flu in 1918 in public health where a Spit Spreads Death, Stop The Spitter, there were signs on trolleys saying, "Hey, Mr. Spitter," again, keep in mind chewing tobacco was a much more popular thing in the North than it is today. The understanding at the time was that flu is being spread by people spitting on the ground and that drying into dust and being tracked into homes and things like that. Not the most accurate understanding of how influenza was spread. Again, spitting on the ground, a lot of this is also a hangover from a previous epidemic of tuberculosis.

And you'll see that some small towns in the country still have laws against public spitting, either because of tuberculosis rules or because of pandemic flu rules.

Farber: I wanted to ask you how effective that message was, and just to get your sense on what kind of information or misinformation was being circulated at the time, and where could you turn for information that was trustworthy? At what point did that emerge in that pandemic?

Hill: Well, 1918 was difficult because in a lot of ways the science, technology was right on the cusp of being able to address this, but not quite there yet. And so in 1918, there wasn't really a strong enough microscope for people to distinguish between a virus and a bacteria. And so they knew that this illness was spreading, they had some idea of how it spread in terms of person to person contact, saliva, really it has more to do with mucus molecules that are mixing with your saliva. But again, they had a vague understanding, however, not quite enough of an understanding to really be able to do much about it. And so the efforts in earnest for a vaccine began in 1918, however, there wasn't a flu vaccine available to the public until 1945. And that again, had a lot to do with the distinction between a virus and a bacteria.

And there were lots of efforts, a lot of failed vaccines in 1918. Initially, the inoculations were developed around a bacterial infection, that was not actually the cause of it. So in 1918, there wasn't really all that much you could do and there wasn't a ton of great, I would say scientific information. There was a public health commissioner in the city, his name was Larry Krusen, and he was a gynecologist by trade. And I hesitate to say that he was not qualified because he certainly was a medical professional, but I think the biggest woopsy in the pandemic response in 1918 was the fourth Liberty Loan Parade, which was held on September 28th, despite public health officials urging the city to cancel it.

I think that will sound familiar to a lot of listeners who might be keeping an eye on the news relating to Lunar New Year parades in East Asia and St. Patrick's Day, parades on the East Coast of the United States that were canceled because of COVID. But in 1918, the two worst things that you could be were a hoarder and a slacker. A hoarder being someone who hoards resources, ration materials for the war effort, a slacker being someone who didn't buy their limit of war bonds. And so the public perception was very much that the Kaiser was a bigger threat than the flu.

Krusen and the City Department Of Health thought that they could contain the spread of flu in Philadelphia, and they went ahead and had this parade. 200,000 people showed up on South Broad Street, and within 72 hours of that event, all 32 hospitals in the city at the time were full. I'm not sure if that answered your question.

Farber: I really appreciate that. How fast did people realize that holding that public event was a grave error?

Hill: Probably a lot of medical professionals and public health professionals realized within that 72-hour window, I would say the general public about two weeks. Much in the same way that COVID takes time and has an incubation period to be aware that you have it, the flu sometimes killed extremely fast, you would wake up in the morning with a sniffle and be dead that evening, we've heard from different family stories and things like that. But again, it's hard to think about and recognize a collective experience until you know somebody who's been affected by that. I think that this really started when it first entered the city was entering the Navy yard, and it was affecting people who worked down in the Navy yard, which at the time was not a residential area.

Again, Philadelphia in 1918 had about 1.7 million residents with an extra about quarter million people here just to work in war industry factories. That is pretty similar to what the population is today, but with a very different density. A lot of South Philadelphia, again down by the Navy yard and also West Philadelphia was very much suburban and there was just nothing down by the Navy yard. So initially, I think the general public probably didn't know what was happening, and by second week of October you couldn't ignore it, you wouldn't have been able to ignore it because you would have been seeing your neighbors, your relatives, your friends dying and a lot of unpleasant occurrences relating to a burial crisis that resulted.

Farber: In the lead up to our conversation, you help solve a family history question for me. My great grandmother died in Philadelphia, in South Philadelphia in the 1918 flu pandemic, and because of your research, we were able to glimpse into that history. I'm curious if you're able to share what life would have been like for her and my grandfather who lived in the house with his grandmother who died in this pandemic. My great, great grandmother was an Eastern European Jewish woman who immigrated to Philadelphia. They lived in South Philadelphia just a few blocks away from the Delaware River and the Coast Guard Station. And I've never gotten a chance to ask someone. Are you able to share about how that family or others like them may have seen this pandemic?

Hill: For sure. A couple of things that are important to note about the pandemic specifically in Philadelphia is that disproportionately recent immigrants were affected by this. So I'm talking a first generation born in the United States, people who came directly and were not born in the United States, and families that very much were new to the area. And that in Philadelphia meant overwhelmingly Irish, Italian and Eastern European folks. And again, Philadelphia had this really glitzy center city area that I think we're all familiar with. But then South Philadelphia, Kensington, Northeast and then Cecil B. Moore Brewerytown were the four areas that we looked at in the most detail for this exhibit, because those were the neighborhoods that we saw the highest number of deaths in our initial data.

And again, we audited all of the death certificates in Philadelphia County from the 1st of September of 1918 through the end of February of 1919, which is how we were able to find your great great grandmother. So for your great, great grandmother specifically, her death certificate tells me that she was born in Russia, so she would have fallen in that category of people who were fairly new to the country and set up in South Philadelphia and most likely were doing some kind of industrial work or labor work, men in the family were at least. And so again, South Philadelphia at this time, when we think about the row homes, again, a lot of these row homes are the same age. Your deed will say 1925, but that's often because the city doesn't have an exact construction date.

So a lot of the row homes that you see today are the same row homes that we're talking about 1918. And today you have maybe three people living in one of these row homes. In 1918, think three families. So this was a very, close quarters living situation. Individual homes were very lucky if they had running water, most likely they didn't have running water and there would have been an outhouse shared between entire block, and so sanitation very much was a challenge. Specifically for, again, I'm looking at your great, great grandmother's death certificate right now.

She's listed as being a house worker, so she stayed at home. She most likely would have been seeing the neighbors around her getting sick, perhaps she would have been trying to help care for them or care for her family, which is something that we hear a lot. Again, South Philadelphia, it's a tight, tight, cramped space, but it also had a pretty good community. Again, a lot of these people came from the same places and were going through similar experiences and trying to help take care of each other. I don't want to anonymize your great, great grandmother by any means, but her story is one that we see over and over again, a recent immigrant to the area, she's in this demographic that we expect to see. She's a little bit older. She's a mother of many kids and unfortunately, she passed away on the 16th of October, which is right in that spot of the second week of October when we see the massive spike of flu dead in Philadelphia.

Farber: Thank you for that. Part of what you are describing is the ways that people coped on an everyday level, house by house, block by block. What stories have you found about the ways that everyday residents cared for each other in the city?

Hill: Well, we've been lucky enough to get a lot of family stories from people who their family was in Philadelphia at the time. We've also gotten some stories from outside of Philadelphia, which has been great. If any of your listeners have a family story, they can actually email it to me at [email protected], and add that. We're hoping to put together a digital scrapbook of all of these family stories. So as much or as little information as you have, we think that's important because again, at the time the historical record was competing against World War I, which was the biggest thing that had happened to anybody really. And so these little snippets of civilian life of the average person's experience—I'm sure they seemed mundane at the time, but today they're priceless.

So to answer your question, we see a lot of volunteerism that went around at this time. I think that people were seeing so much of this political messaging, "Do your part, support the effort," rah-rah stuff, which to its credit, I think people were 100 % prepared to step up to the plate for the most part when they were needed. City infrastructure very much failed pretty quickly during this pandemic, and I've been getting a lot of family stories about one person's grandmother who, she lived near a cemetery where there were workers working day and night to dig holes to try and deal with the volume of dead, and so she would make a big pot of soup and go out to the cemetery and feed the workers as many as she could.

There's another person's grandfather who worked at a dynamite factory, he delivered dynamite basically, and there was a shortage of coffins in the city. And so he started bringing home empty dynamite crates to give to his neighbors as coffins for their children. And we see all sorts of things like that. Seminary students, when classes were canceled, the seminary students were paired off and either sent with a horse and cart to go to different neighborhoods and pick up the dead, or they were sent to the Catholic cemeteries to work as grave diggers. And there were ultimately three temporary mass graves in Philadelphia to deal with this burial crisis.

And so it very much came down to caring for your neighbors, caring for children. Again, that was another thing, we see neighbors with children, if the parents were sick, the neighbors would try to take care of the kids for them so that they could rest, and things like that. Very much a community-based effort to resolve these issues.

Farber: You talking about a city that is undergoing a serious loss of life and the need for immediate solutions to burial—how did mourning change or have to change during the 1918 pandemic?

Hill: Well, it's a little bit of a difficult question because we don't have a ton of documentation, but I will say when a lot of people think about history, they think about the Victorian era and there was obviously a whole song and dance etiquette to mourning in the Victorian era. We're right after that and I think there's still a lot of those kinds of cultural practices in place, but this is also something that differs majorly between now and 1918 is that you had a home wake and you cared for your own dead for the most part. Yes, you would have a funeral director come, there was embalming that might be done depending on your religious affiliation, but there might not be.

Again, there wasn't really the kind of refrigeration that we have available, but really a lot of people cared for their own dead and had home wakes. In 1918, the only specific mourning practice that I've seen that has come out of the flu was the draping of white crepe fabric outside a house where a child had died of the flu. Other than that, it's a lot of similar home funerals, home wakes, but I have seen some family stories where people, again, were aware of this infection spreading. One story in particular, a pregnant woman didn't come to her mother-in-law's funeral because she was pregnant and particularly vulnerable to the flu.

Hill: And some members of her family never forgave her for not coming to that funeral, but when the family member who emailed me this story told me that it was like, "Well, it's a very good thing that she didn't go to that funeral." But I think today we're seeing a lot of these live streamed funerals and only 10 people can be physically present and things like that. I think we probably would have seen in 1918 to some extent those funerals, home funerals, shrinking in size either due to people not wanting to come out for fear of catching the virus or for being sick themselves.

Farber: You have been quoted as saying that there's a very local relationship to this flu pandemic, but in Philadelphia there are no monuments or memorials to those who died. Can you elaborate on that and how you've wrapped your own head around how you've thought for yourself about that fact?

Hill: Yeah. I think the thing that, again, hearing these family stories, the thing that I hear the most is really the trauma from seeing the dead piling up in the streets. This very much became like almost a medieval Europe plague where people were having to put their dead out on their stoops, on their stoops and their yards. And that was extremely traumatic for the general public as you can imagine. Other cities do have some memorial for the lives lost during pandemic flu. In Philadelphia we do not. And again, this is 17 and a half thousand Philadelphians in just six months, 14,000 of those was just in six weeks. So this happened very quickly.

And again, hearing from these families, something that we get a lot is they thank us for talking about this because they didn't know that this was a collective experience because the families, this happened and they may be told a story once or twice and they never spoken about it again. And again, to dovetail this in with the overlapping theme of World War I, you've got this demographic of young men who if they're coming home from war are coming home so traumatized by what they've seen, it has shaken, it was harrowing for them. And they're coming home to their families, to a general public who's just been through this harrowing experience of their own as well, especially in urban centers.

And so it seems to us at the Mütter Museum that people could either choose to celebrate the armistice or they could choose to grieve the flu dead. And they chose to celebrate the armistice instead and try to move on with their lives because it was just too much. And hopefully, we've gotten enough distance from this that we can start to commemorate those people because their families are still talking about them today, there are experiences that they survived and that they remembered have shaped their family for generations whether or not they knew it at the time.

And the efforts that people put forth to try to help their families, their communities are worth the holding and putting on a somewhat literal pedestal if we can. And so we're hoping with the museum exhibit that for now this will function as a memorial for those individuals, but we would like to ultimately get those blue and yellow historical plaque markers in Philadelphia. We're hoping to get at least one of those up. There was a volunteer phone line set up at the Strawbridge's Clothing Store, which is now a Macy's, even a market.

And basically a coalition, kind of a citizens coalition that was meant to oversee and maintain labor conditions and fair pay and the military industry factories, they realized, "Hey, we're not really doing anything with these war industry factories, but here is this whole other crisis that's unfolding." And so they pivoted their attention and set up a phone line at Strawbridge, they just took over one of the phone lines, their Shopper just let them do it to be fair. So you could call Strawbridge's and say flu, you would be transferred to this phone line where someone would say, "Hey, what do you need?" And they say, "We need doctors in Kensington."

They would send somebody out to evaluate what was going on and say, "Okay, they need nurses, they need food. Somebody needs to come pick up these bodies." And they would try to bring those resources to wherever they were needed. And so in a perfect world, we would love to get a marker put up, hopefully there, maybe somewhere else to commemorate these pretty remarkable civilian efforts and experiences.

Farber: You mentioned that there are other cities that have officially remembered the 1918 pandemic, I'm just curious what examples you may share and also if you find anywhere that the World War I memorials make any reference, even if it's passing reference to the pandemic, if there are veterans, for example, who served overseas but ultimately passed away because of the pandemic.

Hill: Sure. I believe, I'm not 100 % certain off the top of my head, but I believe both St. Louis and Pittsburgh do have some public monument to the flu pandemic. Some of these monuments will be just in a cemetery where there might've been a mass burial or something like that, they might not be official public monuments.

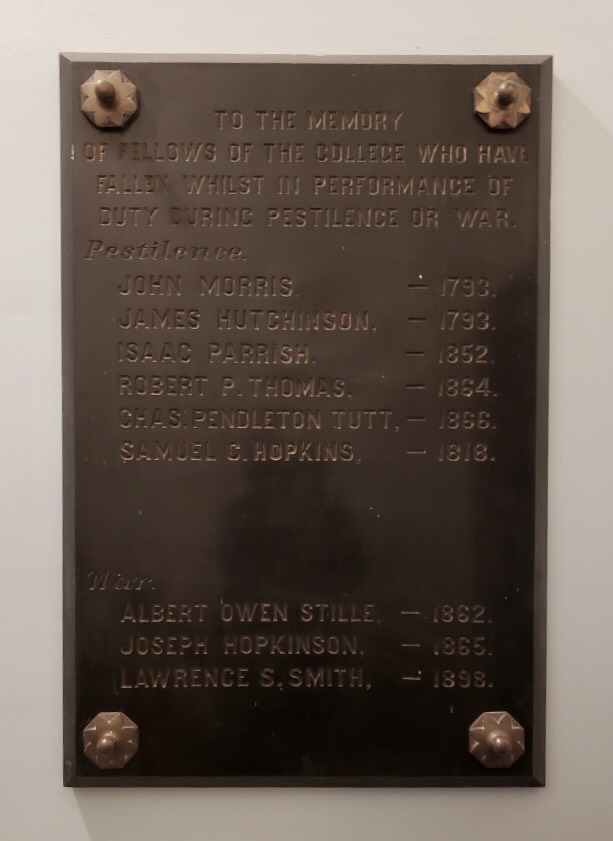

I've definitely gotten a family story about there is a VFW lodge in Delaware named after this soldier who died of the flu before he managed to go to combat, and they had very common story. This, the flu is being spread like wildfire in a lot of these military training camps. And so there are a lot of these soldiers that didn't even make it to Europe to fight, they died of the flu. I would imagine they are represented in a lot of those World War I memorials. It's interesting at the College Of Physicians building, we actually have plaques up, and this makes a little bit more sense for us because we're obviously speaking to medical personnel, but it commemorates fellows of the college who died either in war or during pestilence, and so it's kind of this plaque — it's funny because the way the building's laid out now, it's not really in a publicly available area, but it commemorates members of the college and the fellowship of college who died either from military service or service at a time of pestilence, which the medical authority seems to recognize is one in the same at the time that plaque was put up. Other than that, again, I think there's probably mention of the flu on World War I monuments, but overwhelmingly, you're going to see sculptures of soldiers with helmets and bayonets, and you're not going to see a red cross nurse, you're not going to see the average person, an Eastern European immigrant or anything like that specifically represented.

Farber: And maybe to that point, I heard a talk by our colleague Tiffany Tavarez, and she said that the pandemic that we're facing today is not the great equalizer, it's the great magnifier. And she was speaking specifically about social inequity as something that you see profoundly through the stories of who is suffering and where are hotspots. You've mentioned recent immigrant groups; how did people understand social class or social inequity or stories of race and racism through the 1918 pandemic?

Hill: Yeah, this is a spicy time to be an immigrant or to be a person of color in Philadelphia. So we talked about the immigrant community, but the other thing that was going on at this time is, we're right on the coattails of African-American mass migration out of the South. And so something that we see in different historical documents, and this is something that has been around as long as medicine has been around, but there was the incorrect assumption that African-Americans were immune to the flu. So it was not true, the Philadelphia Tribune, an African-American newspaper from the time has a number of obituaries, but there's always been this perception by a predominantly white medical force that there's going to be some physical difference in how these illnesses impact Caucasian people versus people of color.

That's not true at all, it's very well-documented that this isn't true, but that misinformation is something that we still fight against. I think there's a very loud racial undertone to a lot of the press coverage of COVID-19 because it's something that came out of East Asia. But I think there was very much this pushing into the background of the African-American experience and I've read one really great essay by a gentleman named James Johnson about a prominent African-American family in Philadelphia at the time. But other than that, it's been pretty difficult to find historical record of the African-American experience at this time.

The thing that we have seen a lot of documentation of is a place of burial noted. On some of these death certificates as we were auditing them, a place of burial was noted as "anatomical specimen." We see a disproportionate number of people of color who were noted as anatomical specimens versus white people. We did have white people as well, but our speculative reason for this is that a lot of these people were new to Philadelphia from the South. They were coming from Georgia, coming from these Southern States, and they didn't have family to claim their body and maybe they didn't have money for a burial anyway.

And so here's a cadaver that no one's going to miss if it goes missing, so what happens to it? It goes to a medical school for cadaver study by overwhelmingly white medical students. I think it's important to acknowledge the misgivings of medicine and the exploitive nature. Medicine is great and has done a lot of public service to us today, but we also need to recognize that medicine is inherently a product of the culture in which it exists, and is still something we're dealing with today. So it wasn't just about that immigrant experience. And again, Philadelphians and Pennsylvanians who were white, who had been here for multiple generations were also impacted by this, but overwhelmingly, those families had a lot more resource access and a lot more facilities to avoid the flu.

Maybe they had a property outside of the city they could go to, maybe they had a family doctor who would prioritize them, maybe even just being able to speak the same language as a qualified doctor would have been a barrier for a lot of these immigrant families. It's something that when we were working on this project, we wanted to make sure that we talked about a lot of the parallels that we see today, not just the wonderful heroic efforts of citizens to address something, but also immigrants still have a difficult time accessing healthcare for a number of reasons in 2020.

And a lot of those immigrants are living in the same neighborhoods that were immigrant neighborhoods in 1918, maybe instead of coming from Eastern Europe, they're coming from Southern Asian countries. Maybe the flu isn't the biggest issue of public health in their communities, maybe it's the opioid epidemic. And again, we feel like this has become, "We warned you," the exhibit, because so many things that we talked about over the summer, we had a public health fair at Mifflin Square Park in Southeast Philadelphia, not to too far from where your great-great-grandmother is having listed as live.

And the flu isn't going to be the number one public health concern in that community, and we felt it would be negligent for us to talk about public health and not also offer the resources that seem more pertinent. And I'm glad we did that and those resources are certainly still needed, but now they're also compounding what is also a viral pandemic.

Farber: In retrospect, when you look at over the last even several years, whether it's a cover of TIME magazine warning of a pandemic coming in 2017 or any number of public officials being quoted on the record that there needed to be preparation, this is even if we didn't know what COVID-19 would be, there was a sense of this was coming. Spit Spreads Death opened in 2019, can you take us back to understanding – now it would seem obvious to do it, but for the Mütter Museum – why did you pursue this project and exhibition in the first place?

Hill: The space that the exhibit currently occupies have previously been a civil war exhibit, and so when the time came to start looking at grant funding and things like that for what was going to come next, a lot of people said, "Oh, well, World War I, obviously." And as a health and medicine museum, we didn't want to have a "war gallery". I think a lot of war injuries, especially antique war industries are going to be pretty repetitive, a lot of traumatic injury, a lot of infection, again, there's variation to that, but we didn't want to have a centralized war gallery. And the flu pandemic was something that was concurrent to the World War I, but not focusing on the injuries of war specifically.

And so the topic was chosen due to chronological interest, but also because of the local interests, and because we knew that at any point there would be some public health concern in the news. We were thinking would be something like Ebola or antibiotic-resistant syphilis in Philadelphia or the opioid epidemic, but we knew at any point, there's going to be a public health conversation happening in the news that hopefully visitors can connect this exhibit to and help contextualize for them. Again, I think a lot of us at the museum feel like Harbinger's of doom because we were in the background screaming about this for months and months and months and then we opened it and then six months later it happens.

So it's definitely surreal for us. We knew that the WHO has been saying we're due for another pandemic, we're due for another flu pandemic specifically for a few years now, but we didn't really think the timing would be quite so serendipitous.

Farber: In the months that the exhibition was open, what did you learn that was useful for you as you face the coronavirus pandemic?

Hil Well, I think something that has been a positive that we learned, we did put response cards in the exhibit and so there's a little desk towards the end of the experience with a couple of prompts about past, present, and future, "Do you get a flu vaccine every year? Why or why not?" Things like that. And so it's been interesting to see the responses on those for sure, in that we definitely have gotten some vaccine skeptics in the museum, obviously we're dealing with self-selecting audience, but there's people who come to the museum who are vaccine skeptics and hopefully they've found some information from a source they can trust in both the exhibit and also the College Of Physicians' has a history of vaccines website.

I think it's been interesting for me to see the proportion of vaccine skeptics versus people who trust that and accept vaccine science, and it's also been interesting to see how those two different parties engaged with each other. I think the biggest thing for me that I've learned from the experience of having the exhibit open has to do more with science literacy in that a lot of people not through any fault of their own, but maybe don't know really what a virus is or what it does. And so having a lot of these conversations, if I was leading a tour through the exhibit for example, and this is people of all ages having to explain that a virus is in a lot of ways a living creature in that this is something that can evolve and it has a will to live in a way that maybe we haven't thought about.

I think a lot of people think of viruses as like a computer virus, which is partially accurate as well, but to say, "Hey, the reason that you have to get a flu shot every year is that the flu is always changing and always evolving, think Darwin's Theory of Evolution, but instead of millennia for a change to occur, it's months." And that has very much come up as I've been watching the news coverage of COVID, the fundamental misunderstanding of what a virus is and what it does to our body is something that I hope can be addressed for people of all ages and future education programming. And as we reevaluate and open back up to the world, hopefully it'll be more central to the science conversation at an elementary level.

Farber: I just have one more question for you, it has to do with lessons learned or the perspective that you have. On our Monument Lab Bulletin, we've been talking to artists and curators and asking them about how they anticipate changes, shifts to public space. And so with your perspective in hindsight and now in process, how do you see the next several months or even year unfolding and how will public space change or not change for us if you use the lessons from history in 1918?

Hill: Well, something I want to preface is that we thought about this specifically in the very beginning of the exhibit, the thresholding experience, we pose a couple of questions to people. The one that I think is most important in this context is, "what do people feel and fear and what do you do?" You're asking people to think about what is your responsibility as a member of society during experiences like this? I think culturally now, we are much more accustomed to thinking about ourselves and our micro environment of people, but when you're dealing with something like a viral pandemic, you can't think about it that way, very much has to be a collective rationale and a collective effort.

I'm hoping that after this, that is a little bit more in the front of people's minds, especially when it comes to things like vaccine compliance, because again, we can develop a vaccine for COVID-19 and I'm sure that we will hopefully soon, but that vaccine is not going to be helpful and it's not going to do the things that it needs to do if people don't trust it enough to get it and if people don't have access to it. And so I think those are the compliance with public health and the trust in science as well as the accessibility issues that are glaringly obvious today, hopefully are something that people will start talking about and working to address more . Because again, I think it's really easy a few months ago at least, it was very easy to say, "My neighbor doesn't have health insurance. That's not my problem. They can't go to the hospital. That's not for me to worry about."

Whereas today, your neighbor not being able to get care that they need very much your problem because they are a vehicle in the same way that you are, My biggest hopes for a difference in social etiquette will be, again, just awareness of yourself as part of a collective whole and your role as part of that collective whole, your responsibility to the people around you and whatever your environment you're in, be that the grocery store, at the movie theater, your personal household, and a loss of hierarchy in that I think will be important.

Farber: Nancy Hill, thank you so much for joining the podcast and just for sharing your timely insights.

Hill: Thank you. Thanks for having me. Appreciate it.

Nancy Hill is a museum professional working in exhibits at the Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. She holds a BFA in Illustration, and came into the history of medicine from a medical illustration; raised by a medical librarian, she comes by it honestly. Her focus is in project management, programming, and administration.

Nancy was project manager on Spit Spreads Death: the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic in Philadelphia, and coordinated the planning, research, art performance execution, and installation of the exhibit; she continues work on the project by collecting family histories for an online record, media engagement, and programming for museum guests