Gloria Dickerson (CEO of We2gether Creating Change) speaks with the clarity that comes from living through transformation—not as a spectator, but as a force. Raised in the Mississippi Delta, she was a child of the Civil Rights Movement, shaped by the courage of her parents, Mae Bertha and Matthew Carter, who enrolled their children in the all-white public schools of Drew, Mississippi, in 1965. That choice cost them their home—but it gave rise to generations of possibility.

In this conversation with Monument Lab Communications Director Ashley Tyner, Dickerson reflects on what it means to claim one’s place in the world. From walking into classrooms that were never built to welcome her, to creating new ones through the Mae Bertha Carter Learning Center and We2gether Creating Change, she has spent a lifetime building the future her mother dreamed of. Her work lives at the intersection of memory and action, of healing and insistence.

Dickerson describes growing up just down the road from the barn where Emmett Till was murdered, of the fear and the lessons that shaped her family’s resolve. She teaches children to remember that history, and to see themselves as the answer to generations of prayers. She dreams of a transformed Mississippi—one where sidewalks are safe, groceries are fresh, and young people grow up knowing what it feels like to be full, seen, free.

There’s a deep reverence in the way Dickerson moves through the world, not as sentiment or tradition, but as a practice—an offering. To honor what came before, she insists, is to build something better now. And though she’s often asked how she does it all, her answer is simple, and generous: “The answer to how,” she says, “is yes.”

Gloria Dickerson at North Sunflower Academy, 2016, Drew, MS. Photo by Natalie Griffin. Photo courtesy of Carnegie-Knight News21.com.

Ashley Tyner: Thank you so much for making the time today, Gloria. I’m really honored to be in conversation with you.

Gloria Dickerson: Oh, you’re welcome. Quite welcome.

AT: You’ve talked about the intense resistance your parents faced when they enrolled you and your siblings in Central County’s all-white public school system under the freedom of choice mandate. That story is well-documented in Constance Curry’s book Silver Rights and in the film Standing on MySister’s Shoulders.

GD: Yes. I was raised in the rural area outside Drew, but we got evicted from our home after my brothers and sisters and I integrated into schools in Drew in 1965. We moved to the town when I was about twelve or thirteen years old.

AT: Your mother emerged as a powerful force for justice during that time, and you’ve continued her legacy in really remarkable ways. I’m curious, what were some of the most important lessons you learned from growing up in a large family with a powerful, determined mother?

GD: I learned that whatever you want, sometimes you got to fight for it and you have to claim what’s yours. She said you have rights, and you can’t let anybody take your rights away from you. And so you claim those rights and you don’t turn back. You don’t give up. If they try to stop you, you just push forward. I learned that from my mom and my dad both: don’t let people take things from you that you know is yours. And so I’ve held onto that and I’ve also held on to being able to persevere. You may have some obstacles. People may not like what you’re doing, they may not like what you say, but you have a right to do it and a right to say it, so you do it anyway. And have courage. You got to have some courage. I learned that from my mom, too.

She also said, “Don’t let other people make you feel bad.” I remember that. They may be saying things about you, but just know you’re not that. You’re a good person—don’t let anybody take that away from you. She would say, “Just try to just keep your head up and keep going. Just walk in that school with your head up and your back up and go in and take your seats.” That’s what she would tell us.

AT: That’s great advice. It’s resonating with me right now. I know that the legacy of Emmett Till is deeply woven into the history of Mississippi and into your own life and work. And he was murdered just a decade before you all got evicted. I’m thinking about his mother’s insistence on an open casket at the funeral and how it became a defining moment in the Civil Rights Movement, and how his legacy continues to impact how we understand racial justice, public memory, and mourning. I’m curious how you first learned about the story of Emmett Till.

GD: Oh, I learned about the story of Emmett Till from my mom and dad. I probably was about four years old before I really knew who Emmett Till was. My mom didn’t talk about it a lot, but she would talk about it when we had to come into Drew to buy groceries or things like that. On our way we would pass the barn where he was lynched, and my mom would tell us the story about how he was kidnapped from his home, how he was brought to the barn, how he was murdered, and how his body was taken over to Tallahatchie County and put in the Tallahatchie River. All of her children knew that story. I had some sisters and brothers who were about Emmett’s age. My oldest sister was fourteen at the time when he got murdered, so she remembered it firsthand. She heard about it the next day. She talked about how afraid they were to be outside after Emmett Till got killed.

AT: Do you remember how hearing that story made you feel?

GD: It just really made me wonder why. I kept saying, why would they do that? Why would they kill him? And mama said, well, they say he whistled at a white woman. My dad and mama talked a lot about the things they went through coming up—the obstacles or unpleasant things that they had to do because of being Black living in this world and in the South—being sharecroppers, not owning anything, depending on the white landowner to give them a house to live in. My dad also talked a lot about how Black folk reacted around white folk. If he met a white person [on the sidewalk], he had to drop his head, or he would get off the sidewalk and let them pass.

So all of that was part of the storytelling they did about the things that Black folks were going through at the time. It was just part of normal conversation with us. My mom talked a lot about how she was tired of living in poverty, that she was tired of being poor and she didn’t want her children to go through that. So that’s why education meant so much to her. And she tied it in with Emmett Till as well. You don’t know when white folks would do something to you, because they could do it with no penalties or consequences for their actions. And so she thought, you need to learn as much as you can so you can be more independent. And knowledge, education is the key. Knowledge is power. In order for Black folks to survive in this country, you got to learn something.

AT: That’s a great segue to my next question. I know you’ve worked alongside the Emmett Till Interpretive Center and hosted youth programming connected to Emmett’s legacy and the workshops and the historical markers and community gatherings. You’ve really helped others hold space for remembrance and for truth and for healing. I’m wondering how Emmett’s story has impacted the work you’ve done in the past and that you’re doing in the present.

GD: It’s a story that needs to be told because the history is bigger than Emmett Till. He was killed, he was lynched, but that was the situation in those days. I mean it was 1955 and Black folks were being tortured. He got recognition and he got known because of his mom, Mamie Till-Mobley, who was very brave. He got that because she insisted on this open casket, but the situation was real not just for him, but other young Black kids being killed as well. So it was just the culture, it was what was going on in the world. And a lot of times, younger people don’t understand why they’re in the situation that they’re in today.

Mama told us about how Black folks weren’t allowed to learn how to read. So today, I want to make sure these kids learn their history and learn why Black people weren’t allowed to read, and what the system was like. She used to call it the system. And the power structure—she talked a lot about the power structure, how it’s going to keep you down unless you learn something because that’s the way the power works. I want to help the young people understand that there’s still a power that’s trying to hold them down today. So we need to learn the history and learn who helped us get where we are—who made sacrifices so we can get where we are, who went out and fought for rights and why we shouldn’t take that for granted.

In our classes, we go all the way from slavery all the way up to today in terms of people like George Floyd or Trayvon Martin to try to get the young people to understand what’s going on in the country that allows these kinds of things to happen, but also to give them some tools to be able to avoid it. Even though you’re African American, you’re Black, there’s ways to get around being poor or living in poverty. So that’s why I think it’s important to talk about where we come from and illustrate that we have come a long way, but we didn’t get here easily. We got here because people were willing to put their life on the line. People were willing to fight for it. People were willing to advocate for it, to be an activist for it, to march for it. So they as young people now got to remember that you may have to fight for what you want.

They need to know, I hate to say this, how cruel the world has been against African Americans, but they also need to know that African Americans have persevered and we’ve come up and we thrived. We survived first and now some of us are thriving. We are powerful people. And Mamie Till-Mobley was a person who had that courage to put it out there. Without her courage, [Emmett’s] story wouldn’t have been told and the Civil Rights Movement may not have been sparked.

AT: You had a distinguished career in financial and philanthropic leadership, including your work with MINACT, a career training and support services company in Mississippi, and with the Kellogg Foundation. It helps explain why when you returned home to the Delta, you founded the Mae Bertha Carter Learning Center and We2gether Creating Change. Those spaces focus on history, on the life skills we need to create the best conditions for our future: mindfulness, healing, leadership development. These organizations have really become pillars in your community. Could you talk a little bit about mindfulness and healing? How did they fit into the picture for you?

GD: I worked at the Kellogg Foundation and I got a lot of experience in seeing where the money was going and who it was going to. There was also a lot of investment going in [the Delta], but not very much impact. Things weren’t changing, even though lots of foundations had put in money. The conversation was that things were not changing, so maybe our investment wasn’t working, and maybe we should just disinvest. I was saying, why would you give up on people who need it the most?

My question was, so who’s working on that? And they said, “Well, nobody really, it’s too hard to work on that.” So I said, well, I can work on that. I’ll go back to the Delta and get people to start thinking in terms of possibilities, rather than limitations—get people thinking about, yes I can, rather than no I can’t. I can try to change their mindset. I can try to be a role model for the young people who are coming up now. So that’s when I decided, okay, let me go back. Another reason I came back is that when I went to Drew High School when I was twelve years old, it was such a horrible place. Five years of hell, I could say. And my mama said, it is going to benefit you. Not only is it going to benefit you, but it’s going to benefit generations of people to come. You’re not doing it just for yourself, but you’re breaking down barriers so other children can get a better education as well.

So we did believe in that. When I came back to Drew, they invited me to come back to the school and talk about my history and what I’d done in my career. That’s when I got interested in knowing what was going on in the school system at Drew High School now. Once the young people started talking to me about their experiences at school, it was like, I cannot believe this. I mean, I sat in a classroom for five years trying to be educated and took all of whatever I took and thought that we would make it better and easier for the kids coming up after me. And I come back and this school has just gone down.

It was not the school that I went to. It was not as clean, it didn’t have enough teachers, the kids were walking up and down the hall. They weren’t in their classrooms. They didn’t have books, they didn’t have computers. And I’m like, what do you all do without books? How do you study? “Well, we don’t study. We don’t have books. We don’t have books in the classroom. They just put something on the board and we have to write that down.” I said, so y’all don’t take books home to read and do your homework? “No, we don’t do that. We don’t have them.” I couldn’t believe that. I’m like, I’ve worked hard. We thought we were making things better. Something is not right. So I went back to work with these students and try to help them get a better education.

When I came back, I was also concerned about the third-grade readers. They didn’t pass their tests. They weren’t going to go to the fourth grade. So we started teaching during the summer, trying to get their reading skills up, because I wanted them to come out of poverty. I remember living in poverty, and I remember how hard it was. I remember how hungry I was sometimes, and how I wanted to eat sometimes when I couldn’t. I didn’t like that, and I don’t think these children ought to have to go through that as well.

I said, they need to find a way to lift themselves out of this poverty. Our schools were failing them because they were not getting what they need. It had been drilled into me as a child that you got to get some knowledge if you want to thrive. So I said, how can I not come back and help? Even though I went through a lot, I was blessed and it paid off. And now it’s time for me to give back and try to help. So that’s why I came on back to Drew.

When I got into the classroom with the kids, they were talking about how I was giving them more support and more encouragement than they were getting at home. They advised me to start not only working with them, but also to work with their parents and talk to them about possibilities, about changing mindsets. So I started some adult classes. We had about three or four cohorts of adult classes. The adults talked about their stress and their blood pressure. It’s bigger than just not having food—it was affecting their mental health.

I am a certified mindfulness teacher. I went and got certified in mindfulness when I started talking about mindsets. We started mindfulness classes with the adults first, teaching them how to release some of that stress of living in poverty. You don’t know how you’re going to pay your bills. You don’t know how you’re going to buy clothes for your children. So we started mindfulness, and we’d meditate and do things like that. I also talked to them about parenting skills—the way we treat our children, where our children are reaching out for support and nurturing, and that we need to do a better job of working with our children. We recognize the fact that a lot of us have experienced trauma because of poverty and health issues and not being able to find a doctor. So we talked with the adults about that and did the mindfulness classes with them.

AT: Your answers are really beautiful. Thank you. I’m thinking more about the youth and how so much of your work centers on young people, making space for them to learn their history, develop those life skills and grow into the next generation of leaders. We’re talking about the importance of empowerment and belonging and mindfulness. What is your dream for the future of Mississippi, especially for its young people?

GD: When I got back here, I said this community looks like people here live in poverty, with all the dilapidated homes and the bad roads and the bad schools. People don’t have jobs and things like that. My dream was to try to transform the community—to help them start thinking more about their future and preparing for their future. We can transform the community and make it look better, we can tear down the dilapidated homes and build new ones. People can stay in school more and either learn a trade or go to college. That’s what I want for the kids. When they leave the program, they go to college or get a trade—and stay here rather than leaving. When people come back to Drew, I want them to see something different and say, “Oh, this place looks really nice and I think I’m going to make my home here.” That’s what I want, to see some families do that, to see young people do that.

That’s my dream. We got to break the cycle of poverty. We got to break it. Often people tell me hope is not a strategy. Yeah, hope is not a strategy, but without hope, there is no strategy. And so we do a lot of work to get people to say, “Things can change. I can see the change. I can see things changing now when I walk out my door. I see flowers growing in the neighborhood. I see houses going up. I see dilapidated houses coming down. My children have sidewalks to walk on when they get ready to go to school. My children have a park that they can go to and get on a swing set.” You can start with those things.

We wanted some recreation for our children. So we got together and volunteered and made a park. I said, you name it, we’ll find a way to go get it. That’s the approach I take. And that’s why we got an online grocery delivery service. They wanted a grocery store. We tried and tried, and that didn’t work, so I said let’s go to the next alternative. If we can’t get one in our community, maybe we can go out of the community for the people who don’t have transportation, get them to order groceries online, and we can bring them. They don’t have to leave their homes. It’s just trying to find ways to do things that people think are impossible and making the impossible possible, and starting to believe that even though your socioeconomic status is not good, you still can make a difference in your own life. That’s my dream of what Drew would look like, where it’s got nice streets and nice homes, and eventually a grocery store comes back, and people start to open businesses here. We can improve our community and the children can do well in school. A lot of my kids have done well. They come through the program, and they have their careers now.

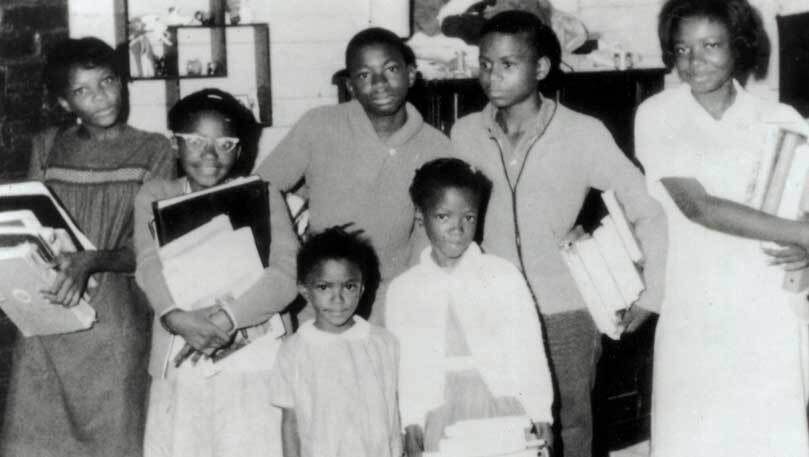

Portrait of the Drew Carter siblings, year unknown, Drew, MS. Photographer unknown. Photo courtesy of Gloria Dickerson.

AT: I love what you said. I’m thinking about how you’ve served your community in so many capacities, from a nonprofit founder, to a spiritual mentor, to an elected official. In 2015, you became the second woman ever elected to the Sunflower County Board of Supervisors. And through it all, you’ve really modeled a form of leadership rooted in listening and integrity and care. I think that comes across in the way that you describe your dream for Mississippi. What does servant leadership mean to you, especially as it relates to Mississippi and to your dream?

GD: Well, it means that I’m here to serve. I’m in this world to serve. That’s why I came here. Part of my purpose is to help others, and serve others. Even though I’m an elected official, I often say I’m not a politician. I’m a public servant, meaning I’m here to look out for other people. I have my obstacles, but I’m at a point right now that I can look around and see how I can help make sure we don’t leave anybody behind, we can reach back and bring somebody along. What servant leadership means to me is that you’re always in the mode of who can I help? How can I help? What things can I do? How can I improve? What kind of courses should I take? What do I need to learn to be able to help people as much as I can? I realize that I don’t know everything, I don’t have all the answers. What answers do I need to get out of them in order to move this? But it’s really just putting in the effort and saying, okay, Lord, I’m making a difference in this world and I’m leaving it better than I found it. I’m leaving it better than what it was when I was in the seventh and eighth grade, where I suffered day after day after day. Now it’s a better world where people get along with each other. They don’t look at each other as, I’m better than you. Everybody can start to come together and say, we’re all human beings and we’re all God’s children and this work is to help each other. That’s where I am.

When I moved back here my sister asked me, “Why are you doing that? Why are you moving back into the hood?” And I said, that’s what I really feel like I ought to be doing and I think I need to help. And somebody would say, some people can’t be helped. But I decided to move back anyway. My husband kept asking me, “Well, how are you going to do it?” And I said, I read this book that said the answer to how is yes. Once you start asking how, you really are trying to talk yourself out of it. So I said, I don’t know how it’s going to work, but I’m going to do what I can do and I’m not worried about how right now. I’m just going to be persistent and persevere until I can make a difference.

AT: The answer to how is yes. I love that. And I think that’s so instructive at this moment right now.

GD: We don’t know how, but we got to do something. We got to make a change. So that’s why I do it, and I enjoy doing it. It seems like I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing in life. This is it for me. I put a lot of my own money into it. I could have traveled the world if I wanted to, but I just like it here, and I like what I do. I like teaching about Emmett Till, bringing his memory along and making sure he is never forgotten. His death was the catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement, and so we honor him for that reason. I regret that it happened to him, but I’m thankful to his mom for making sure that he didn’t die in vain.

AT: Yes. This issue’s theme is reverence, and your work feels so deeply aligned with that word. As you’ve described today, you’ve created spaces of real calm and clarity and empowerment in a region so often associated with struggle. I’m thinking about your work as a servant leader and curious what the word reverence means to you?

GD: I guess my work is something for generations to come, and I hope it would be revered as something good.

AT: Yes, you’re talking about your legacy.

GD: And my mom’s legacy—she did a great job with what she went through and what she sacrificed for her children and what we sacrificed for her. I often talk to the young people about how grateful I am that my enslaved great-grandfather and all those people who were enslaved worked so hard and prayed so hard so that the next generation would have more than they have. And I often think about how I can see myself as the answer to their prayers. They might not have seen it while they were here, but I can see them saying, “This is what we wanted when we were enslaved ourselves. For you to be able to get up and move around the way you want to move around, go where you want to go, do what you want to do, work where you want to work, and enjoy your day where you want to enjoy it. This is what we wanted for ourselves, even though we might not have gotten it before we passed away, but we as your ancestors are so thankful that our prayers have been answered. We can look down now and say, okay, we did good.”

I know after so many years, a lot of enslaved people were hopeless. But somebody saw something they could do and somebody tried to help them escape. Somebody prayed, somebody sang those songs and they lifted their spirits that way, trying to get through it, and they had prayers in their heart that one day African Americans wouldn’t have to live like that. And I’m so thankful they did because if they hadn’t, I wouldn’t be where I am today. So I think about my ancestors and I say, thank you all for what you did. It was a struggle. I have a lot of reverence for them, that they came through that and put me where I am today, if that makes sense to you.

AT: It makes so much sense to me.

GD: And now I can do the same. I can help the way they helped. I may not see it all before I leave here, but that’s my goal, that one day you’ll be able to thrive and won’t have so many obstacles against you because of the color of your skin. There are some people out there in the world today who think that African Americans do not have obstacles against them because of their color—they think those days are over. But I see so many signs that it’s not over: they take money from the public schools and don’t teach the kids how to read. Just like the enslaved people weren’t taught to read, our kids are not being taught what they need to be taught. It’s still not an equal playing field. Your schools are not like our schools. A lot of people get offended when you talk about that. They don’t understand why you just can’t pull yourself up by your bootstraps, but they don’t understand what’s going on in the world either, though. You don’t know that our children are not getting a fair shake.

That’s one of the reasons I started the field trips. The young people don’t get to leave their community at all. They only know what’s in the Delta. I took my kids on trips to Florida for eight years, one hundred kids a year, because I wanted them to see another part of the world. I wanted them to see that there’s something else out there besides what they see in their community. Someone said, “Ms. Dickerson, thank you for bringing me here because I’ve never been out of Mississippi before. I’ve never been out of the county before. And you brought us all the way to Florida and we went to Disney World and we went to class and we enjoyed our classes and we learned so much. We got to ride an elevator and an escalator. Never done that before.” You don’t know what these kids are not exposed to. You think it’s a level playing field and they’ve never seen an elevator? These kids need to know that there’s a world out there that’s not like the way they live. That is not all poverty. But I say, first you got to learn something, then you got to earn something. And then you got to go out and have some fun because we came in this life to have some fun too. Have vacations, and come back and work and earn some more. That’s what life is supposed to be about. Not about struggling all the time, and not going anywhere but out your front door in the morning and back in the door in the evening.

That’s not life. You’re not living like that. I want to expose the young people to that so they can start to think in terms of possibilities. They say, “How am I supposed to think in terms of possibilities when I’ve never seen anything else?” That’s what I try to show them, things that they’ve never seen before. Quoting George Bernard Shaw, Robert Kennedy used to say, “Some men see things as they are, and ask why. I dream of things that never were, and ask why not?” I live by that. I see things that never were, ask, why not have a walking trail in this community? Why not have a YMCA or a gym in this community? Why not? Instead of talking about how bad it is, why not create something different? That’s the way I am.

AT: Why not?

GD: Why not.