4,591.

That’s the number of covid deaths reported on Thursday, April 16, 2020 in the U.S.

4,591 is more than all the U.S. soldier deaths in Iraq since 2003 (4,574).

3,856.

That’s the number of COVID deaths reported on Friday, April 17, 2020 in the U.S.

3,856 is more than all the U.S. soldier deaths in Afghanistan since 2001 (2,443).

Both numbers easily exceed the death count from the terror attacks on September 11, 2001. And without doubt these figures underestimate the true scope of the pandemic’s daily tragedy, because many states are only reporting deaths confirmed by a positive COVID-19 test.

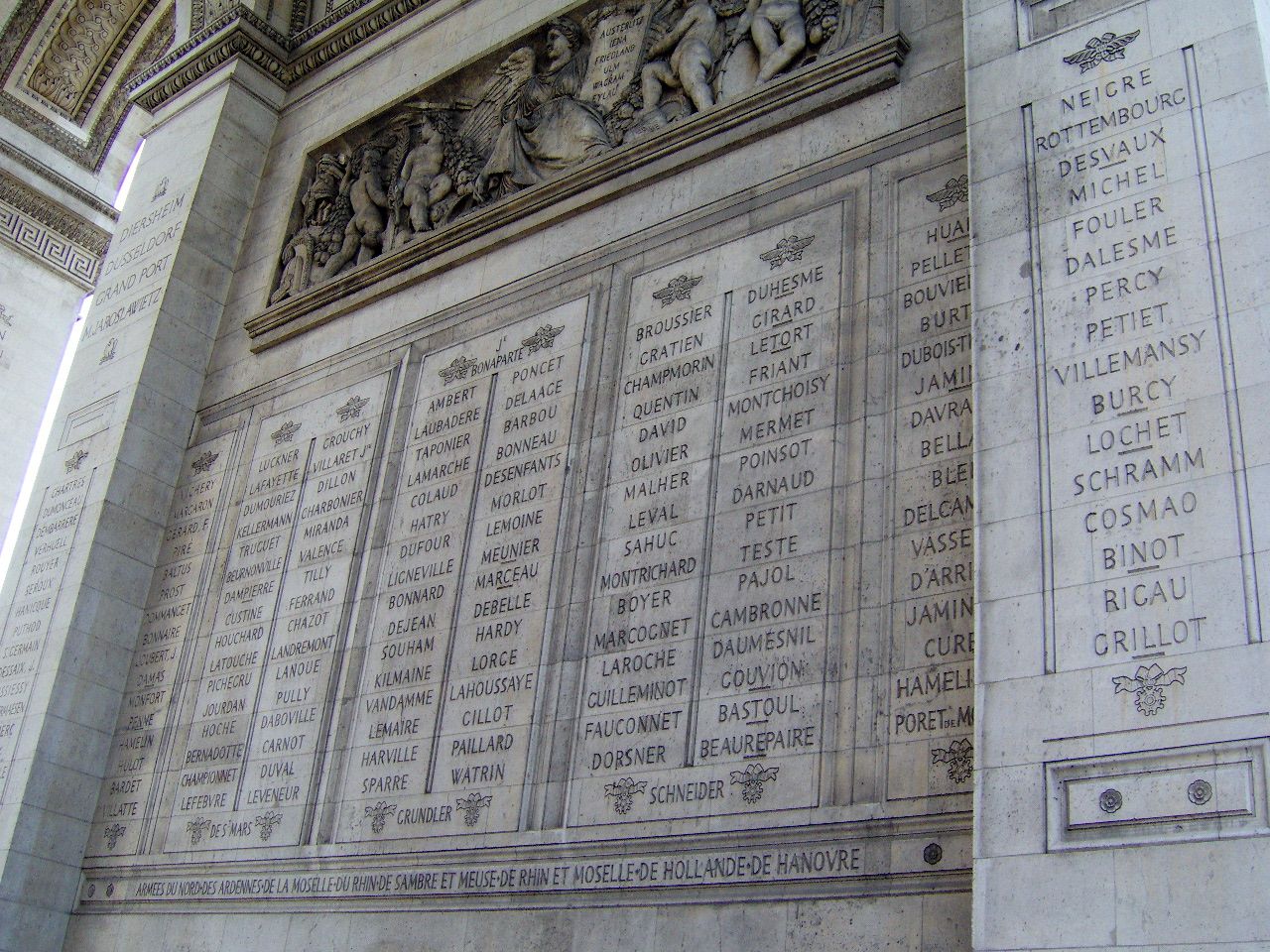

Over the past century or more, the counting and identification of the dead have become increasingly central to how we make sense of national tragedies and how we remember them in monuments. It is hard to believe now that Paris’s Arc de Triomphe, finished in 1836, had a mere 660 names chiseled in stone when the Napoleonic wars it commemorated had taken the lives of millions. Still that paltry number overtopped all other monumental lists of the dead up to that moment. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as the scale of death in wartime reached previously unimaginable levels in the U.S. and Europe, the practice of naming took off. By the 1920s, some battlefield monuments for World War I, like the Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium, included more than 50,000 names of the dead.

In the mid-twentieth century, victims of civilian tragedies such as hurricanes and fires began to share space with war memorials in the commemorative landscape, sometimes with their own lists or counts of the dead. Over time a new common sense emerged: after September 11th victims’ families and politicians alike could simply assume that the monuments commemorating the dead would have names and numbers.

The naming of the dead turned ungraspable statistics into evocations of actual people one knew or could imagine. On the battlefield or at Ground Zero, many of the dead had disappeared, their bodies turned to dust or dumped into unmarked graves. The monuments erected in their hometowns or on the battlefield gave their kin and their comrades a chance to mark and ritualize losses that had been swamped by crisis and chaos.

In the midst of the coronavirus we are witnessing this same swamping effect. Everyday a new set of victims replaces the ones that came before, in hospitals, morgues, and news reports. The sick die in isolation from their loved ones, in overcrowded ICUs, nursing homes, jails, and prisons. Nurses and doctors make heroic efforts to get a family member on the phone or screen to say goodbye, but even if this succeeds a basic funeral is often impossible. In a nonstop crisis, the dead are discarded.

Will these unknown, uncelebrated dead ever get the recognition of a public monument, or will they disappear again into a swamp of national mortality statistics? Denialists would have us believe that the victims of the coronavirus are just routine deaths, no more remarkable than other lives lost every year to the seasonal flu or automobile accidents. But of course there is nothing routine about this pandemic: the exponential rate of COVID death in the past few weeks is far more terrifying than any routine cause of mortality, and much more comparable to the conditions of warfare.

Ultimately, what makes the COVID numbers so difficult to contemplate is that far too many of these deaths were preventable, had the national response been swift and sure-footed. As a nation we must not forget these dead because we must not forget how and why they died – written off by a national administration indifferent to human suffering, especially of those most vulnerable or oppressed. To make a real reckoning with the numbers requires nothing less than a monument of truth and reconciliation.