A common belief is that our monuments, historical markers, and naming of buildings, parks, or streets are permanent. However, our understanding of the past is always changing through the experiences of each generation and that influences the history we value and want to see commemorated. In St. Louis we have shown that monuments are not always lasting, and how we define our history through our built landscape is constantly evolving.

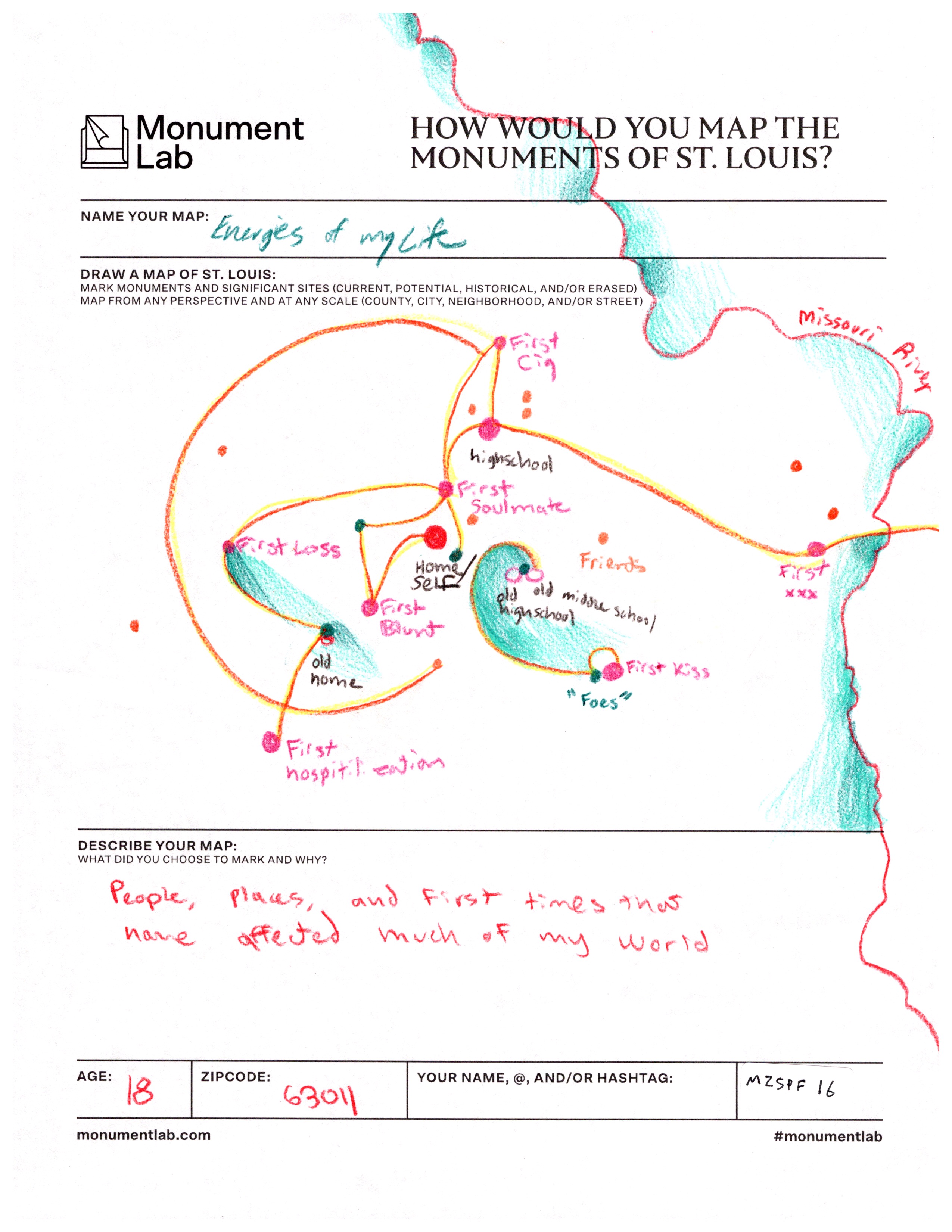

In the map-making project led by Monument Lab and the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, we see a snapshot of this evolution through a community-built data set of marked and unmarked sites that currently define St. Louis. This latest iteration of monument imagining presents a fuller view of history that redefines our commemorative landscape and asks for a new method to monumentalize people, places, and events.

St. Louis’s commemorative priorities have always been in perpetual revision. St. Louisans changed their German street names to prove themselves unsympathetic to Germany during the First World War. In 1960, the monument to Union General Nathaniel Lyon, originally located near the St. Louis University campus, was moved across the city to Lyon Park.

These are only a few examples. Monuments have been destroyed, relocated, and renamed as part of our continual reinterpretation. Politicians and grassroots uprisings, urban renewal and community artists, racism and anti-racism, and many other effects have all contributed to the evolving historical narrative. The recent removals of the “Memorial to the Confederate Dead” from Forest Park and Christopher Columbus Statue in Tower Grove Park are also a part of this constant pattern of contesting and reshaping commemoration in St. Louis.

Even the city’s longest running placemarking effort had the same fate. In the late 1920s the Young Men’s Division of the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce led a citywide historical marker initiative that erected over one hundred bronze tablets, metal and wood markers, and paintings of local history scenes placed along the riverfront and throughout the city.

The Young Men’s Division selected marker topics they believed were most important for the city to commemorate. Without a democratized process, they initially focused on history through their lens by mostly marking sites of white and male views of the past. Initially their markers reconnected memory along the riverfront to people and places of French, Spanish, and English colonialism. They were also interested in sites related to Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

As the project expanded further inland through downtown, their efforts widened beyond the history of colonization to tell a more complex history of St. Louis. A few historic sites of European immigration, slavery, artists, and even popular restaurants became marked. Visitors to downtown St. Louis encountered markers with titles such as “Ruins of Old Turnhalle,” “Site of First B‘nai El Synagogue,” “Site of Lynch Slave Pens and Prison,” “Site of Birthplace of Charles Marion Russell, the Noted Cowboy Artist of Western U.S,” and “Site of Tony Faust’s World Famous Dining Place.”

Their efforts lasted nearly half of a century but the sites they chose to select were likely read by hundreds of thousands of people and influenced how the city saw its history for a generation. Much like the other examples, only a few of their markers remain in their original locations; most were lost during the mass demolition to create Jefferson National Expansion Memorial and Busch Stadium. Sites such as Bernard Lynch’s Slave Pen are no longer marked, leaving a wound in the commemoration and recognition of injustices that built the city and continue to shape it.

Reviewing the history of commemoration in St. Louis suggests monuments are more temporary than permanent and their historical interpretation should be more dynamic than static. Combine these values with the data from the study and we can see how St. Louis history is always transforming. The participants share with us a different monumentation that is far more complete by encompassing sites of our full cultural history, sites of social justice and to memorialize racial terror, and sites that divide us and sites that unite us. Ultimately, the participants show the importance of community involvement in commemorative efforts and recasting how we define our collective past.