“Emmett Till was ‘the big bang,’ the Tallahatchie River was ‘the big bang’ of the civil rights movement.”

— Rev. Jesse Jackson, Sr.

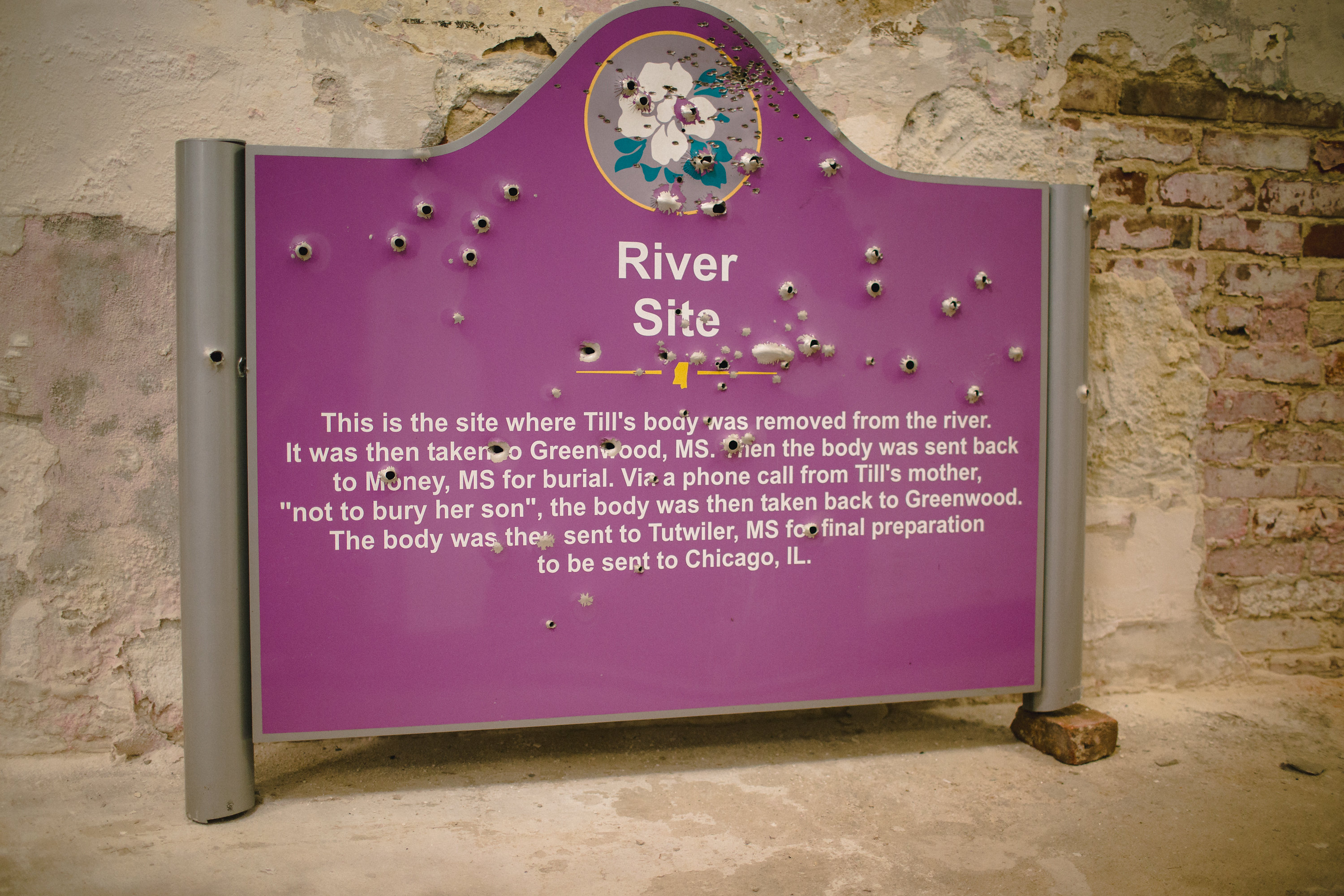

Bullet-proof historical marker for the memory of Emmett Till at Graball Landing, Tallahatchie River, Sumner, MS. (Photo by Langdon Clay. Image provided by the author)

Graball Landing is the site where Emmett Till’s body likely came out of the Tallahatchie River, setting off a chain of events that gave birth to the modern Civil Rights Movement.

Emmett Till, a Black youth, left his hometown in Chicago in the summer of 1955 to spend time with friends and family in Mississippi. His mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, reluctantly let him go. As he boarded the train, he gave her his watch noting that he would not need such things where he was going. His mother decided to give him his father’s ring as a gift instead.

Just days later, Emmett Till’s body was taken out of the Tallahatchie River at Graball Landing after a brutal lynching. His great uncle, Mose Wright, acknowledged that he could not tell if the body belonged to his nephew because it had been so badly disfigured. Fortunately, there was a ring attached to the body with initials of Emmett’s father, Louis Till.

For many in Tallahatchie County, this shameful piece of history was best left ignored. However, the members of the Emmett Till Interpretive Center (ETIC) believed it was past time for acknowledgment. The ETIC was formed in 2005 by a multiracial group of residents of Tallahatchie County to confront the historical trauma of Till’s murder. In 2007, fifty-two years after Till’s murder, Tallahatchie County offered the first and only formal apology to the Till family for our role in the injustice.

Graball Landing was founded in the 1830s as an outpost for a newly created slave plantation. Over thirty enslaved people were brought to Graball to clear the wilderness. The land was likely purchased from the government after the removal of the Native American population.

The ETIC erected a historical marker in 2008 at Graball Landing. In 2014, researcher Dr. Dave Tell of the University of Kansas and author of Remembering of Emmett Till gave reason to believe that the ETIC had placed the marker in the wrong spot and that the site where Till’s body was removed was located a few miles away at a place called Pecan Point. Regardless, the sign has become a national inflection point.

Over the years, this site of solemn remembrance has gained national attention as a result of repeated acts of vandalism against the commemorative signs that the ETIC placed there. These commemorative signs have been stolen, thrown in the river, defaced with acid, riddled with bullet holes, and spray painted with the letters “KKK.”

In March 2019, a group of students from my alma mater, the University of Mississippi, posed with guns in front of the shot-up sign, and the images circulated nationally that July. In September 2019, the ETIC replaced the shot-up sign and dedicated the country’s first bulletproof sign to commemorate a civil rights memorials. Two months later, a white supremacist rally at the site was caught on security cameras, again drawing national attention. These despicable acts of vandalism and white supremacy have not deterred the resolve of the community to commemorate the site. We now aim to reclaim the site with a national memorial.

Residents of Tallahatchie County are committed to changing the symbols of hate and oppression associated with the county. For years, residents have protested to remove white supremacist symbols like our Confederate Statues to the Lost Cause. In November 2020, Mississippians voted overwhelmingly to accept the new “In God We Trust” magnolia state flag to replace the old state flag containing the Confederate emblem. Now is the time to move forward with a Mamie and Emmett Till National Memorial.

For me this struck a personal chord. My son was born on September 9, 2020. He is a sixth-generation Tallahatchie County resident. His ancestors established Graball Landing and profited off the system of racial capitalism and white supremacy that would eventually lead to the murder of Emmett Till. Although my son will not be able to go back in time and change what his family did, my hope is that I can lay the groundwork for him to be a part of a new story.

The local family who currently owns Graball Landing has leased the land to Tallahatchie County for fifty years with the intention of developing a memorial on the site. On July 7, 2020, the governor of Mississippi signed H.B. 1621, an act to authorize the Tallahatchie County Board of Supervisors to lease the river site for 50 years for the purpose of memorializing Emmett Till and allowing our community to create a new narrative for itself.

The community process of designing this memorial is just as important, if not more, than the resulting memorial itself. Before we begin designing the memorial, we need to engage the community in reflecting on larger questions: What is Emmett Till’s legacy today? Why is it so difficult to protect a memorial honoring a Black child? How much has changed in Tallahatchie County since 1955, and what work remains to be done? How does structural racism continue to impact Tallahatchie County? What values do we want to see reflected in this national memorial? How does the current national conversation around Black Lives Matter intersect with Emmett Till and the history of Tallahatchie County? Can Tallahatchie County and the United States exist in a post-white supremacist society and what will that look like? By bringing the community together, the process of creating something can itself facilitate the important conversations that need to happen.