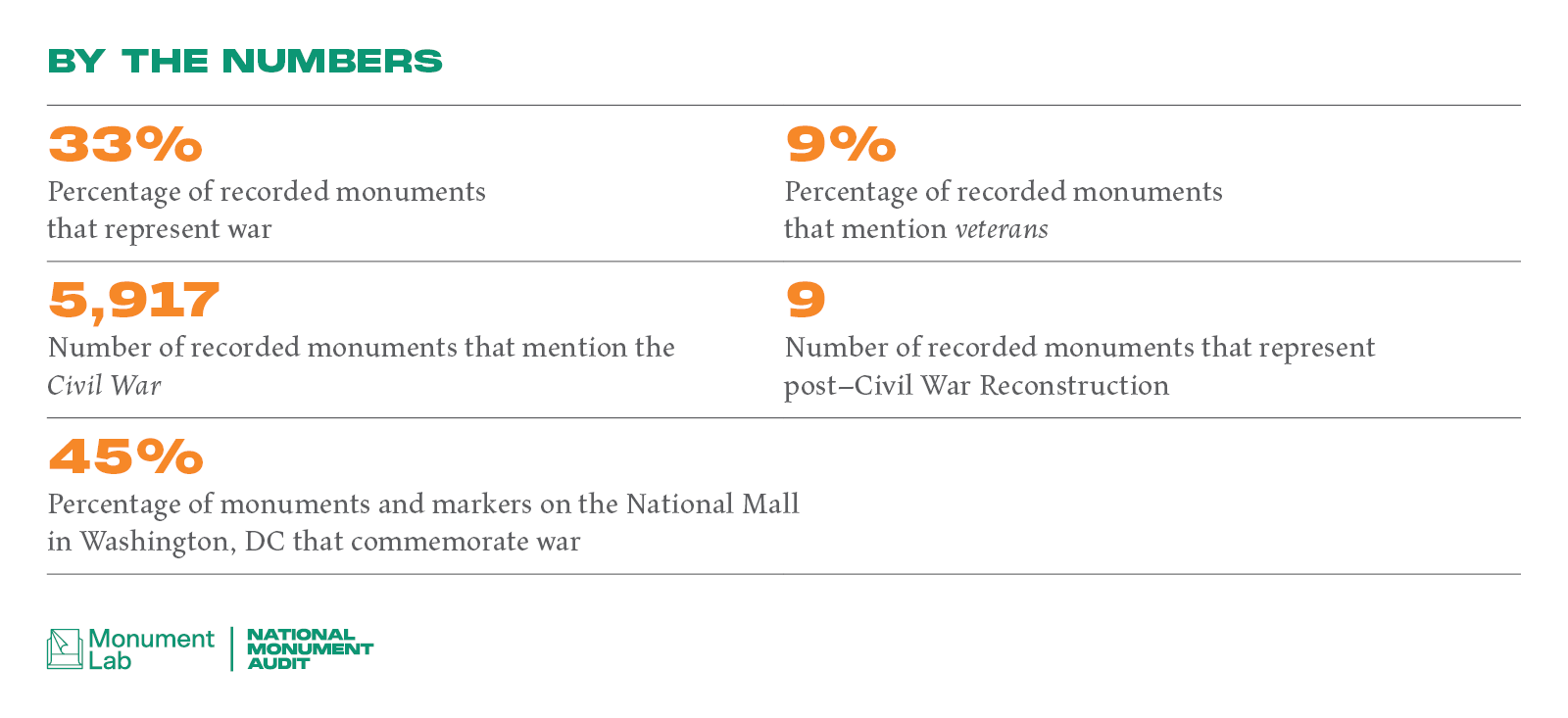

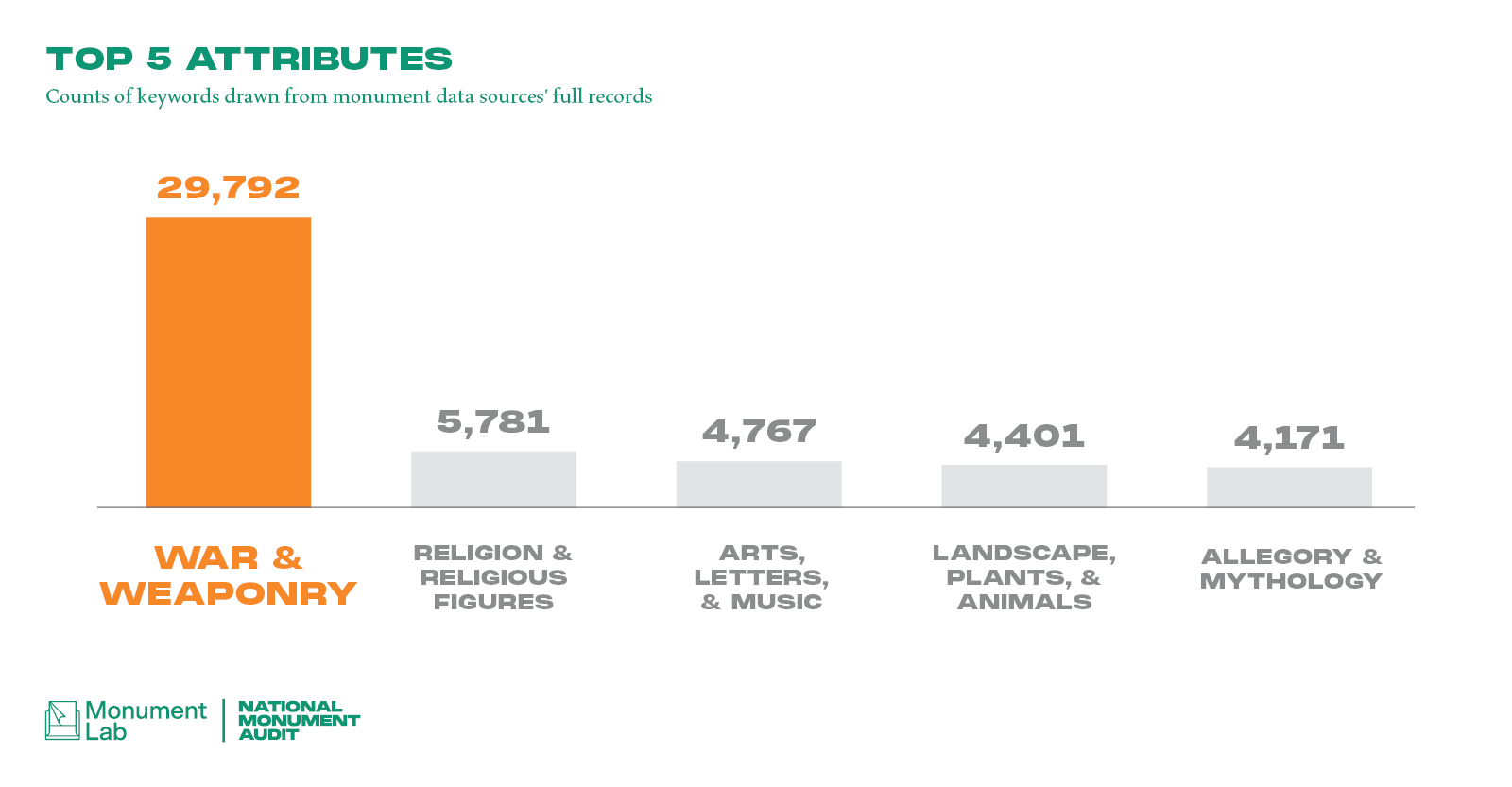

Violence is the most dominant subject of commemoration across the nation. Thirty-three percent of conventional monuments in the data set, inclusive of memorials, include mentions of war. Walk through many towns and cities across the country, and this data will be reflected in the symbols and stories one encounters: statues of generals immortalized on horseback with cannons and weaponry, or long memorial roll calls of local fallen soldiers carved into stone. One is far less likely to encounter other kinds of stories embedded within communities in monuments—for example, those that center civil rights, public health, neighborhood activism, and education. This dynamic and discrepancy reflect broader investments and values we hold beyond our monument pedestals.

The toll of war on our country is channeled through our monuments. Despite their preponderance, our monuments generally minimize the social and environmental costs of warfare for our veterans, their families, and our communities.

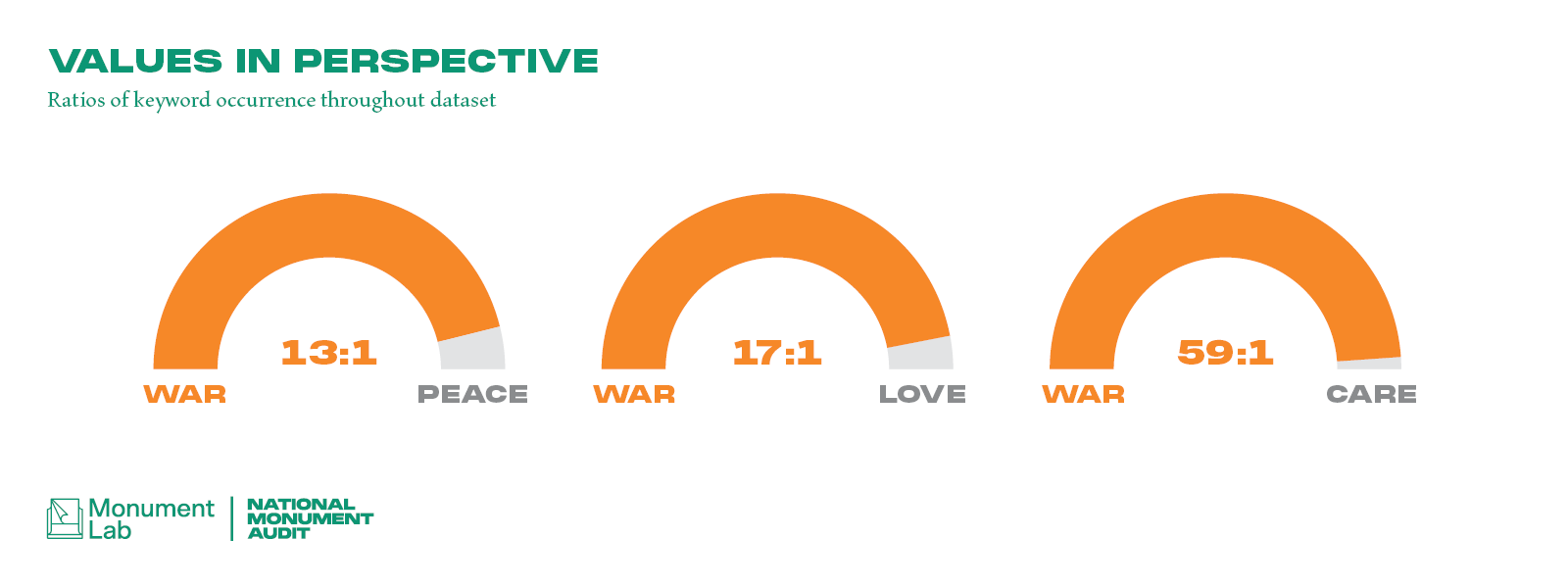

For example, our data set contains 5,917 records for Civil War, but only nine records for monuments commemorating the Reconstruction period following the war. The ratio of records that refer to war and peace monuments is 13:1. The ratio of war to love is 17:1. The ratio of war to care is 59:1.

In their content and form, war monuments and memorials also obscure the violence of combat and conquest. A broader approach to indexing monuments of war and conquest, looking through and beyond the data, reveals additional insights into the geography of American conflict. For example, Mount Rushmore National Memorial (Gutzom Borglum, 1941) was dynamited out of and carved into the face of the Lakota’s Tunkasila Sakpe Paha sacred space and remains a site of struggle over broken treaties today. Entering the term massacre into our study set returned one hundred records: fifty-three massacre monuments memorialize the killing of white settlers or soldiers by Indigenous tribes, while only four represent the killing of Native populations by white settlers. There are no results for memorials recognizing massacres of other people of color, despite at least thirty-four documented massacres of Black Americans between 1865 and 1876 alone.1

The monument landscape has long reflected the country’s history of war and conquest. It also speaks to the national crises of harm, trauma, and grief that are embedded within it. We can envision an approach to commemoration that honors veterans and weighs the extensive toll of war and conquest, and that looks to transform the monument landscape through stories embedded within communities that foster repair and healing.

1. Equal Justice Initiative, “Documenting Reconstruction Violence: Known and Unknown Horrors,” Reconstruction in America: Racial Violence after the Civil War, 1865-1876, vol. 1. (2020): 42-52.

CALL TO ACTION

Reimagine commemoration by elevating stories embedded within communities that foster repair and healing.