The National Monument Audit reminds us that monuments are not timeless, permanent, or untouchable. Each and every monument changes over time. Many are made to last with enduring quality— but they are not made to last forever. They are installed, by design, with an expectation that years later someone else will have to contend with their alterations due to common maintenance, weathering, wear and tear, and other transformations in the social and physical settings around them.

Official records highlight changes through several factors, including dates created, dedicated, altered, added to, and removed, as well reports calling for maintenance and detailing decay, disrepair, and routine damage. Monument records rarely reflect plans by the original sponsors to anticipate maintenance nor efforts to make room for interpretation by future generations.

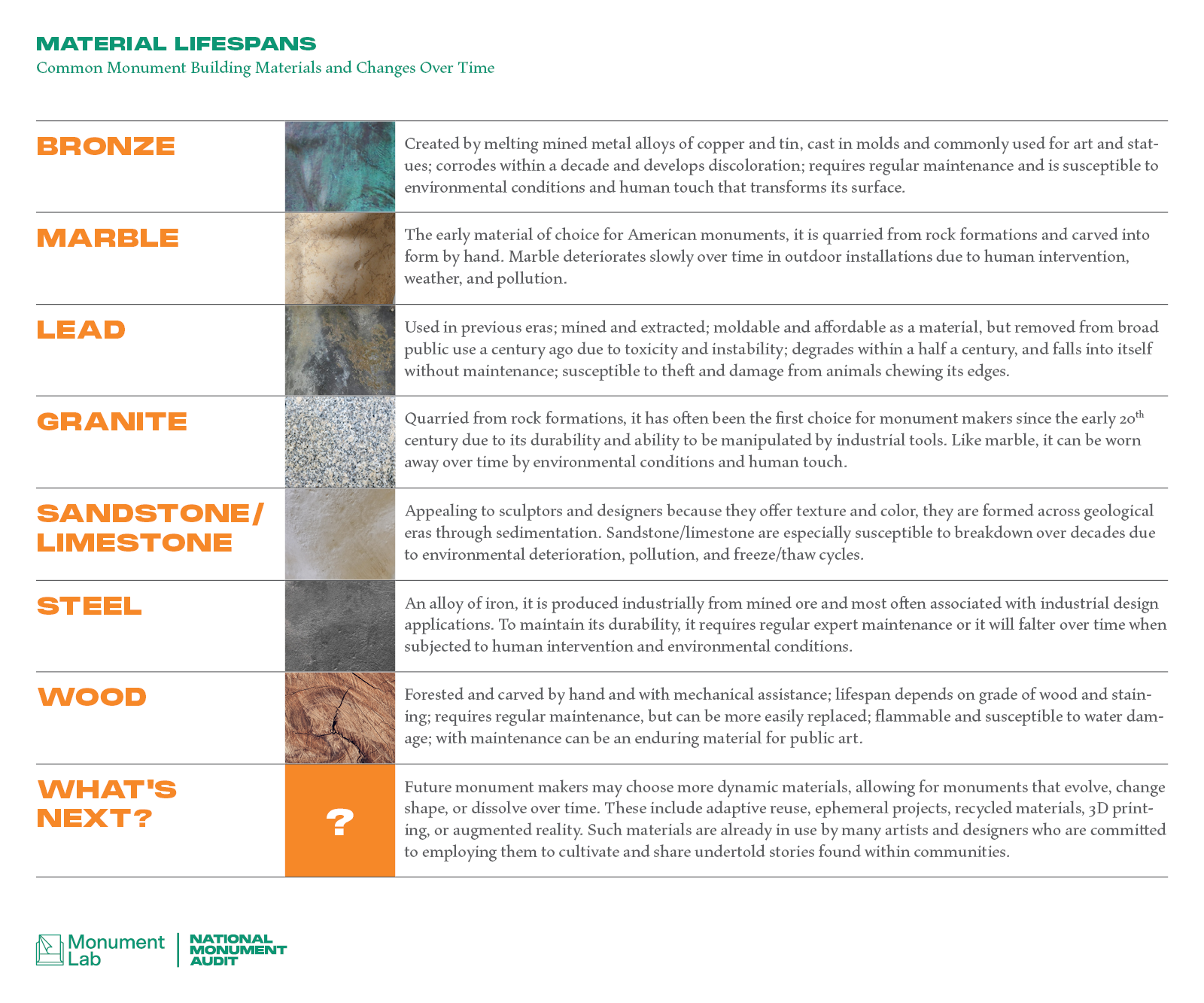

Conventional monuments are created out of materials that require preservation and restoration to withstand the elements. The country’s largest source of monument data, the Smithsonian Institution’s Save Outdoor Sculpture survey, estimated that at the time of their study in the 1990s nearly half of all outdoor sculptures were in disrepair, largely from rust, mold, pollution, and deferred maintenance.1 For example, without routine maintenance, bronzes change color from brown to green, while marble and granite stain and erode based on human interaction and weather conditions. To survive these changes, monuments require people to provide money as well as expertise to preserve and repair them. These kinds of investments require resources, time, and political influence.

Communities also routinely change monuments by making modifications, including gestures big and small, that upkeep and augment sites dedicated in the past. From the addition of new plaques and wreaths to large-scale renovations, public officials and civic leaders have developed a wide variety of strategies to alter individual monuments, assigning further meaning to them in their respective locations. For example, 342 names have been added or changed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall (Maya Lin, 1982). The names of sixty-two Black soldiers that were originally left off were added to the Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regiment Memorial (Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1897) in Boston dedicated nearly a century prior.2

During times of social upheaval and conflict, monuments can undergo drastic changes, ultimately transforming their physical contexts and altering the ways that people are able to engage with them. Through our study, we encountered multiple occasions when people relocated or removed monuments for reasons other than political controversy: for example, aesthetic updates, the dedications of new parks, moved roadways, and scrap metal drives during World War II.

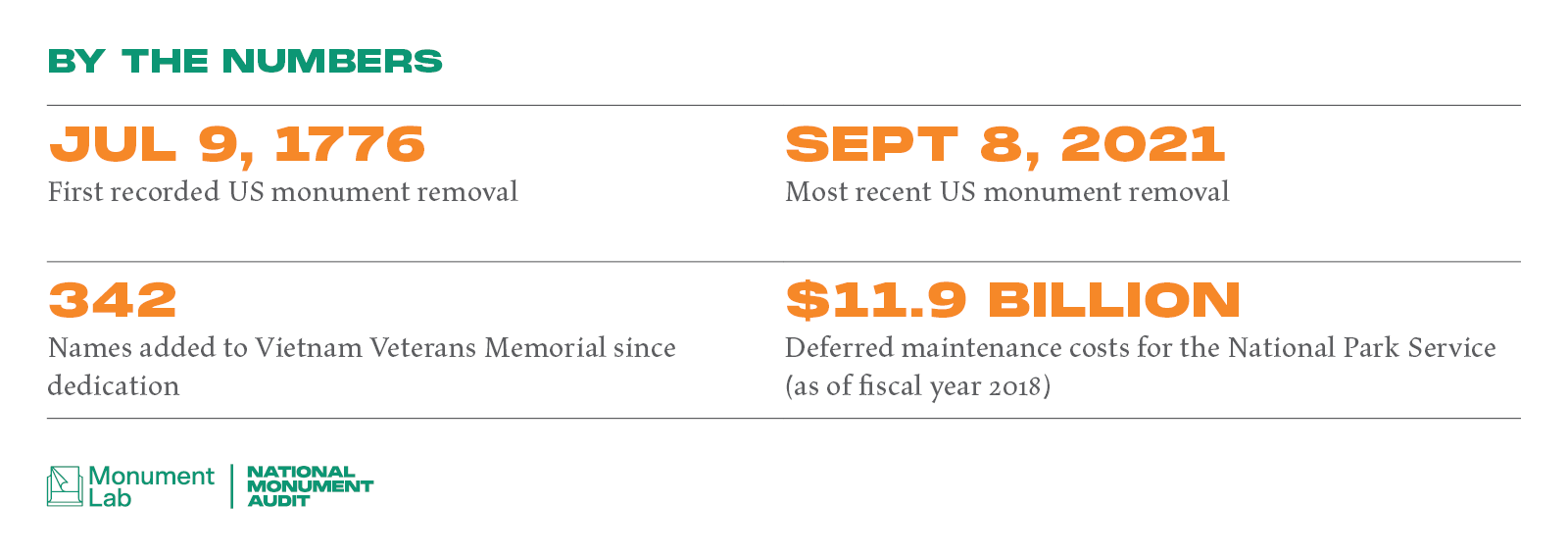

Despite the tremendous investment in building and maintaining the sanctioned monument landscape, there is also a long legacy of communities resisting ideologies through the strategy of monument protest and removal. For example, the first recorded monument removal in the United States was on July 9, 1776 (statue of King George III of England, New York, New York); as we write this, the most recent removal was on September 8, 2021 (statue of Robert E. Lee, Richmond, Virginia). Though the removal of monuments remains an area of great attention, we estimate that 99.4 percent of conventional monuments remain in place, with each one undergoing continual social, environmental, and material changes in clear and subtle ways.3

1. “Tips, Tales, & Testimonies: To Save Outdoor Sculpture!,” Smithsonian Cultural Heritage, Heritage Preservation, Inc., 2002, https://www.culturalheritage.org/docs/default-source/resources/cap/outdoor-collections/tips-tales-and-testimonies-introduction.pdf?sfvrsn=81370b20_2.

2. “The Names: Vietnam Veterans Memorial,” Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund, https://www.vvmf.org/About-The-Wall/the-names/; David Mehegan, “For These Union Dead,” Boston Globe Magazine, September 5, 1982, 32-33.

3. This figure is based on the highest estimate of three sources that track monument removals (Wikipedia, Toppled Monuments Archive, and USA Today) divided by 50,000, which accounts for our study set (48,178) rounded upward for gaps in record keeping.

CALL TO ACTION

Build a new, deeper understanding of how monuments live and function in communities, examine the forces that drive their installation and upkeep in relation to civic power, and reflect on how and why they evolve over time.