In November 2016, colleagues asked if we could march together in a protest following the election. Until that moment, my passion for political disruption had never overlapped with my career in the art world. Following the march we went for coffee to warm up, and while everyone sat around the table recapping the day’s events I found myself marveling that, in all of my years of activism, it had never been as easy as it was on that day to organize. It had been a terrible week for all of us. The group at the table was composed of all arts professionals, and with the excitement radiating from our corner of the room, I was absolutely certain that this was a group that wanted to take action. I returned home that evening feeling inspired and hopeful to have found kindred spirits in the most unlikely of places: the art world. A day later Roxanne Jackson’s Facebook post went viral and Jessamyn Fiore invited me to serve as curatorial advisor for a public art exhibition and fundraiser that would eventually become a global art movement. Since then, my curatorial ethics and strategies have developed and challenged me to ask myself, “what message pertaining to the rights of womxn do I seek to address through my own practice?”

In 2017, we organized and launched the Nasty Women Exhibition in New York City. On that cold January opening night, over 2,240 people walked through the doors of the Knockdown Center in Queens, and in just three hours we raised over $35,000 for charity. While the show was not affiliated with any political party, it was a direct response to the national elections that had taken place the prior November 2016. Our group’s immediate concern was the threat posed to womxn’s rights--a threat that persists today. The role of curator often helps define what constitutes a public, and as the curatorial advisor I intentionally decided to foster a wide spectrum of responses that reached beyond the art world and urban areas. Moreover, I was committed to letting the public shape the definition of a nasty womxn. Within the first three weeks of announcing the open call, we received over 400 submissions from all around North America and the world. The response to the open call from womxn around the world was so intense that the letters spelling out NASTY WOMEN at Knockdown Center were literally dripping with art.

Ultimately, we sold over 680 artworks and 100% of all proceeds were donated to Planned Parenthood. Before, during, and long after our show launched, responses to the post on social media continued to flood in from all over. In fact, so many people wanted to know how to organize a Nasty Women Exhibition in their own location that we immediately made the decision to openly share our organizational strategy. Overwhelmed with the prospect of having to manage these sister-shows, we created a list of standard best practices for other venues to adopt - and a global movement was born.

We only ask that you stick to two main points:

- Please be mindful to reach out to and include a diverse group of female identifying artists.

- The exhibition is a fundraiser to raise money to support an organization of your choice that is supporting women’s rights (it could be national or local – your choice).

—Excerpt from Organizing Your Own Nasty Women Exhibition

As a light-skinned womxn of color, when I was invited to participate in the capacity of curatorial advisor I had two immediate requests. The first was that the exhibition be entirely inclusive. The second was that it be inclusive to all womxn artists. The word “womxn” is, of course, a relatively new inclusive term that serves to include any person who identifies as a woman, including our cis and trans sisters who have been historically excluded in earlier feminist movments here in the United States. After reviewing over 700 artists’ statements for this show I have to point out that it is highly unlikely that the womxn artists from more marginalized groups would have contributed their work if we had included men in the open call. The artists who participated in the show at Knockdown Center were responding explicitly to the call for “Nasty Women Artists of all ages, races, religions, sexual orientations, gender or non-gender identifications, economic backgrounds, immigrants and non-immigrants,” and the submission statements reflected both the necessity and urgency of those voices. Curating an international exhibition in such a mammoth space as the site in New York City, my queer conscious was overwhelmed with the potential spectrum of responding artists. The immediate and massive reaction to my colleague’s Facebook post had made me hyper aware of the position I was in as the curatorial advisor to the group. I knew that I could never select the work of an established artist over that of a high school student submitting artwork under the moniker of their preferred gender for the first time, nor would I ever want to. In keeping with the intention of letting the public shape the conversation, I could only hope this open call might offer individuals a voice, when at that moment so many of us felt unheard.

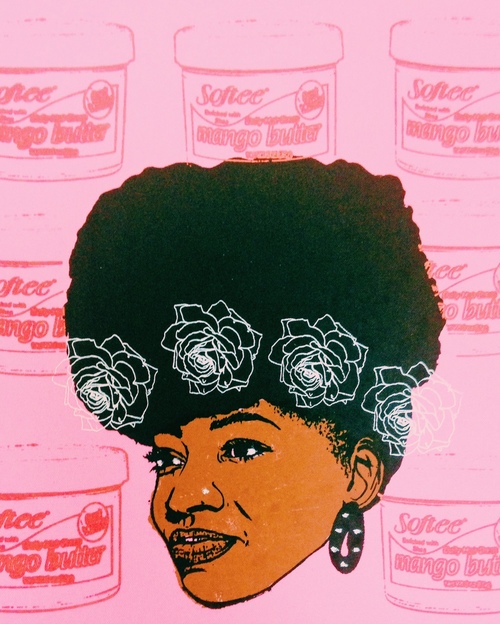

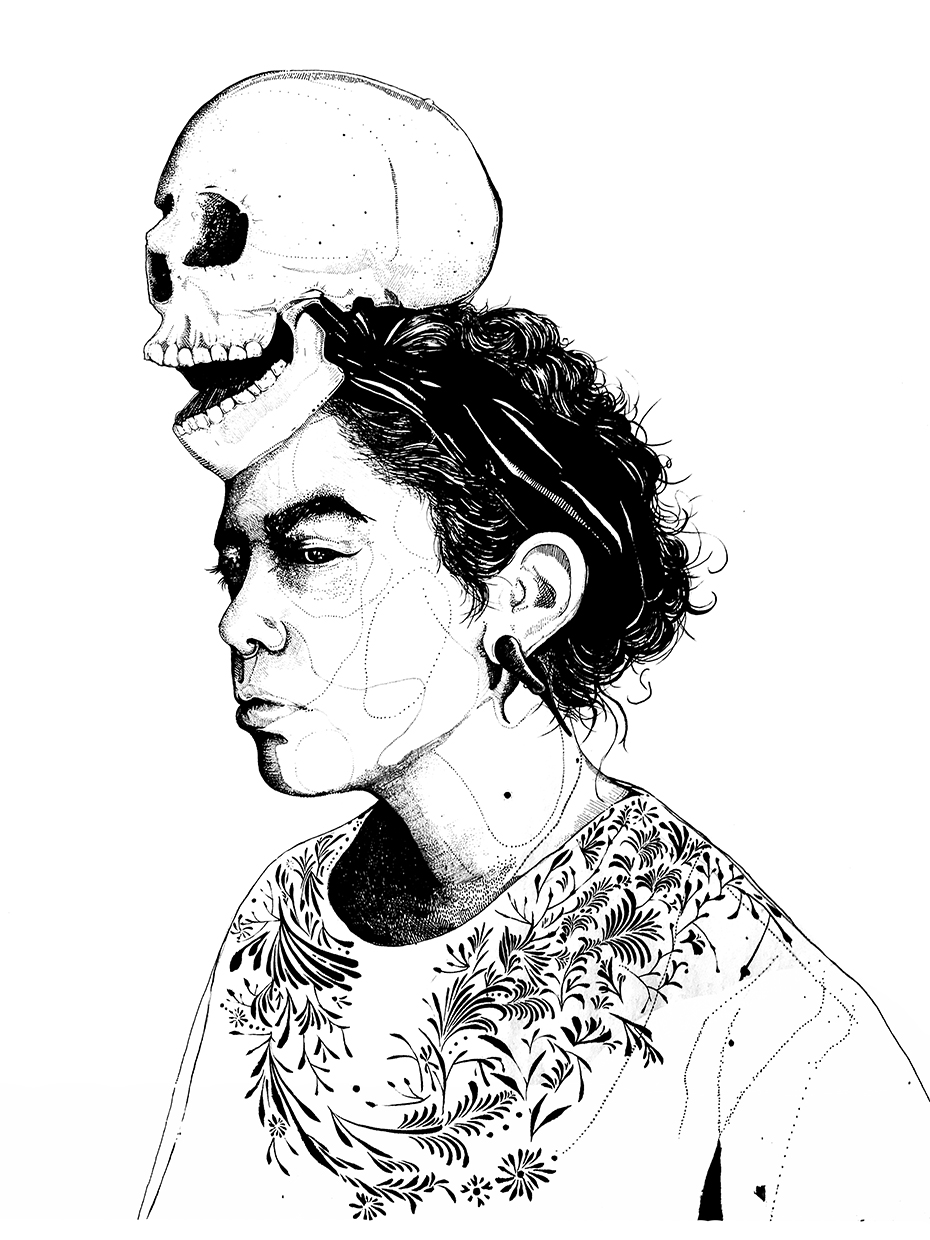

Up until this point in time my curatorial practice had never overlapped with my political activism. I’m an unapologetic Anarcha-feminist and I was passionate about keeping the New York City exhibition womxn-focused. A week into the launch of the website the question of “who is a nasty woman?” came up amongst the group, and my position was then what it is now: that anyone can be a nasty woman as long as they are applying as a womxn. In the earliest stages of development, reviewing submissions was my primary role, and therefore I had the responsibility of selecting what images would be sent to the press. I was conscious that my own selections primarily featured work created by, or representing, womxn from more marginalized groups. This can be observed in the earliest artworks to circulate within the media: Wythe Moss, Kaylee Koss, Angela Pilgrim and Heidi Wiren Barlett’s portrait of performance artist Tempestt Farrar were some of the earliest artists whose artwork was featured in print. As I read through each and every artist statement, I was constantly reminded of the privileged position I occupied, and even more driven to listen to what womxn all over the world had to say. Although the group would be considered egalitarian - even with what eventually amounted to eleven lead organizers and over 150 volunteers - at the time I believed myself to be one of only two leads who identified as a person of color. As an academic and arts professional this was not an unfamiliar environment for me - but on a personal note, a new feeling of self-awareness arrived with this position of privilege. I had the opportunity to do something I had only ever dreamed of accomplishing: fostering representation in the arts for minorities and marginalized groups.

One question I have repeatedly fielded over the last four years is Does the exclusion of male applicants from an open call feminist art exhibition negate the message of inclusivity? My answer? No, I don’t think so. There are many exhibitions that honor womxn and include male participants. My whole life I’ve seen museums, galleries, and whole events that feature all womxn but were curated entirely by men. Moreover, other Nasty Women Exhibitions have welcomed submissions from male applicants, and that’s wonderful! I’ve curated exhibitions that have included artwork by men in the past, but in 2017 the world was not lacking the voices of men. It was important for the New York City show to showcase all types of artwork from diverse womxn all over the world. Furthermore, every artwork had to be unpacked, inventoried, labeled and hung, followed by logistics of sale. If we had invited men to participate, our labor would have been dedicated to them equally and their work would have been taking up space that a womxn’s work would have otherwise occupied. I thought, and still feel, that if men are interested in supporting the movement in New York City, they can do it in ways other than submitting their own artwork. They could (and did) assist on builds, administrative responsibilities, and anything else that doesn't compromise the core message of the exhibition. In fact, the gigantic letters that welcomed visitors at the Knockdown Center were designed and executed by a gentleman artist who supported the project from day one. I appreciate, and fully support, the discourse surrounding male allies who want to celebrate womxn, support womxn artists, identify as "feminists," and desire to submit work that has an anti-chauvinistic sentiment. However, now more than ever it feels important to provide space for the exploration and celebration of womanhood.

I am proud that my contribution to our ongoing fourth-wave feminist crisis was advising our team to curate a show entirely of womxn artists and set a model for grassroots fundraising. While I am forever indebted to the feminists that paved the way for me, I am woefully aware of the absence of representation, diversity and inclusion that plagued the first three chapters of the women’s movement. While gains were made, the reality is that those first waves were heavily marred by racism, classism, homophobia and transphobia. In comparison, fourth-wave feminism and the age of technology have created the perfect storm. Our current technological developments help us organize in a flash, communicate our concerns to the world, and provide a public platform for critique that was previously missing. Indeed, as I write this article, galleries and museums the world over are having to recalibrate, redesign and rethink the ways in which to curate and display artwork as a reaction to the post-COVID-19 new normal. I do believe that there is room in the canon of contemporary art for the evolution of many different types of exhibitions, the likes of which we have yet to even see.

The first Nasty Women Exhibition at Knockdown Center facilitated urgent conversations by creating a safe space for womxn artists to express themselves and their womandom. The guidelines we provided to fellow organizers built a solid framework for that space, while other shows from around the world expanded on that foundation. My experiences all these years later have provided me with enough confidence to take a moment to reflect on my role as a curator in a feminist public art movement that continues to shift and evolve, much like the world itself has transformed since November 2016. Just like venue capacity and size restrictions, the format of each show adapted to accommodate the needs of the event and the host community; At the heart of the movement that is what the movement was all about: strengthening local communities while creating bonds of solidarity across the globe. Since January 2017, each subsequent iteration has felt like a resounding ARE YOU WITH US?!, to which communities around the world have replied, YES. I believe that the Nasty Women Movement was not born from a question, but instead from a statement. When shaped through the lens of history and womxn in the arts, the 2017 Nasty Women Exhibition loudly stated, This isn’t about you. This is about us.